By Edward Tse

China with its massive population and growing purchasing power has become a critical market for many foreign multinational corporations (MNCs). Over the years, different growth models have been adopted. Some have chosen to build their China presence organically while others have formed joint ventures with Chinese companies, or a hybrid approach. Some other MNCs decided to acquire local companies to accelerate their growth in China. Most of these acquisitions were with local privately-owned enterprises (POEs) because of simpler ownership structure compared to state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Unfortunately, many of these acquisitions resulted in foreign MNCs and local companies getting a nasty shock. MNCs’ record of acquisitions of local companies is at best mixed, and in many cases, complete failure. Management of these MNCs have a go-to list of excuses for why these M&A deals failed (of course after the fact), with the target of the blame always being their acquired local companies. Often they claim these local companies are dishonest, cooking their books to make them look more profitable than they actually are, or that the eagerness to expand into the China market led to shoddy due diligence work that would have discovered these issues beforehand. Of course, in a number of cases this indeed was the truth and some of the falsifications were serious. However, these reasons do not fully explain all the cases that didn’t work out. (By the way, not all of the “local companies” accused of these improper behaviors were “Chinese”. Some of these companies were actually started and owned by foreign entrepreneurs. However, in the remainder of this article, let’s just call these companies “local Chinese companies” for sake of simplicity.)

Source: Baidu

In taking on acquisitions as a growth strategy for China, foreign MNCs normally assume integration of the local companies’ operations into the MNCs’ own operations to be an imperative. In fact, these MNCs’ management believe that integration is the best way for them to “add value” to the local operations because of their more superior management know-how and that synergies can be created via better economies of scope and scale – indeed a very common practice for MNCs in their M&As in many parts of the world. So why not doing the same in China? In order to ensure a smooth transition, the MNCs would typically offer financial incentives to senior managers of the local companies – often the founder himself or herself – to stay, at least for a certain period of time, until “integration is complete.”

From the local Chinese entrepreneurs’ standpoint, many of these acquisitions also didn’t realize their original expectations, but for different reasons. They were led to believe that under the wing of the MNCs who claim to be far more sophisticated and professional than the local enterprises, their own companies would have a better chance to continue to sustain, their brand would continue to grow, and that their companies would become a “long-lasting company”, or ji ye chang qing in Chinese. As the “integration” proceeds, many of these entrepreneurs begin to discover problems, the most common and biggest one being that foreign companies don’t really understand how to operate in China (lao wai bu liao jie) and how the original senior management are either forced out or leave of their volition after seeing that they are no longer welcomed or no longer “belong” there.

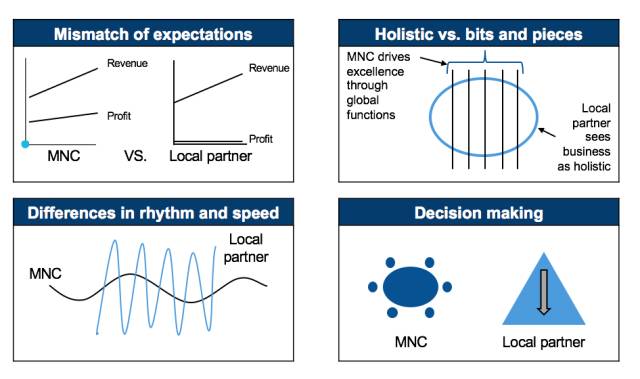

Like every situation in life, there are pearls of truth found in different perspectives of the same story. Both sides have their valid arguments, but the one-sided views often miss the overall picture. Based on what I saw through my consulting work in China, I would however suggest that the biggest contributor of these issues is the differences in behavioral approaches and norms between the parties involved. I believe there are four key reasons: 1. mismatch of expectations, 2. holistic philosophy vs. bits and pieces philosophy, 3. differences in rhythm and speed, and 4. decision making systems. (See Exhibit 1)

Exhibit 1:

MNCs vs. Local Chinese Companies

Mismatch of Expectations (top line vs. bottom line)

Foreign MNCs typically care for both top and bottom line growth. This is business 101. Most of these companies have been in operations for decades, if not for over a century. It’s only natural that they look for both top line and bottom line performance. In fact, that’s why many of them chose to enter the China market in the first place. After all, China is a high-growth market compared to more mature markets. The fact that many of the foreign companies, especially the larger ones, are publicly-listed makes the case of profitable growth even more compelling because the management of these companies need to be responsible to the capital markets. This can be very different for Chinese companies, at least for some of them, especially when China’s economy was growing at high speeds and opportunities seemed to have presented themselves left and right. For many Chinese entrepreneurs, their first priority was to grow, or to “land grab”; so top line growth was often more important than bottom line growth. Of course, this strategy wouldn’t work forever. But for a certain period of time, it was the go-to strategy for many Chinese entrepreneurs. Clearly, this divergence in points of view often led to difference in strategy, level, pace of investment, and if not properly handled, mistrust. Of course, the laws of gravity also apply in China. And companies, regardless of their ownership, need to be profitable. However, for some of the companies during certain periods of time, their priorities could be different.

Holistic Philosophy vs. Bits and Pieces Philosophy

Many foreign MNCs have built excellence by function across geographies over long periods of time. These global functional capabilities became the backbone of these companies’ well-being. And, they naturally desire to apply these capabilities across all geographies in the world. China wouldn’t be an exception. To this end, many MNC executives become specialists in their own right. They are very good at what they specialize in, but as a result, they are often less aware of areas beyond (or the “broader context”) and the often need for making necessary trade-offs. On the other hand, given that the Chinese owner/CEO often builds their company in a rather short period of time in an environment that is often ambiguous, imperfect and fast-changing, and filled with a large range of stakeholders, they frequently need to make tradeoffs across many dimensions and their solutions are commonly an optimization of numerous factors facing various constraints. So, when someone with a single-dimensional view looking for consistent, global standards and someone who has always been juggling different considerations across multiple dimensions in an evolving, imperfect environment have to work together, they would inevitably run into conflicts. These conflicts, if not properly managed, could lead to frustrations and mis-trust.

In their eagerness to “help”, many MNCs would assign some of their own people to fill in key management positions to “assist” the Chinese entrepreneurs. These people would typically be Mandarin speakers, either ethnic Chinese or non-Chinese who’ve been in China for some time. The MNCs often assume that “since these people were trained in my system and they know China, they must be able to help.” Unfortunately, that turned out to be not always the case. From the Chinese entrepreneurs’ standpoint, these people while technically sound, often lack the ability to see beyond their narrow specialty and to understand broader implications of a holistic perspective of the business. So, these attempts often ended up with mixed records at best.

Differences in Rhythm and Speed

Compared to foreign MNCs, Chinese POEs typically are far speedier, more agile and more adaptive. Foreign MNCs are much more focused on checks and balances, and deliberations which makes them slower. Many Chinese POEs are quite willing to quickly build a good enough product or business model, throw that into the market, and let the market tell them what they need to improve and adapt. This is of course risky, and unacceptable, if the product hinges on quality, safety and security. However, in cases of new business models, the willingness of the market to accept imperfect business models can actually be pretty high, especially in the first trials. But consumers do appreciate companies whose business models or products cater to their needs and utilize fast feedback cycles to improve their offerings to the consumers’ taste. In these situations, Chinese POEs tend to have an upper hand over more established foreign MNCs. So when these two different speeds and rhythms come in contact with each other, incompatibility naturally occurs.

Decision Making Process

Many Chinese POEs came into existence in less than couple of decades and many of them were able to achieve lots of growth piggybacking off China’s fast pace of economic growth. Many are still run by the owner who typically grew the company from nothing to its current size. These organizations are typically concentrated to the one person or a small group of senior executives with the founder/owner still calling the shots. In this structure, the organization is very top down and often hierarchical. While there are people who by title are leading various functions such as marketing, logistics, sales, or R&D, more often than not, they are merely carrying out orders from the most senior person(s). In a way, the founder/chairman/CEO in reality is the synthesizer of information and the decision-maker for all decisions affecting the company, no matter how large or small. Decisions often come from the top of the pyramid with the rest of the management simply there to execute. On the other hand, foreign MNCs, especially large ones, are organized with clearly defined roles and responsibilities throughout the chain of command. In a local POE, a senior VP of Marketing’s role is likely to execute the vision and strategy developed by the most senior person in the company. In an MNC, an individual with the same title will be actually responsible for the marketing strategy.

Source: Baidu

So, what should foreign companies do as they consider M&As in China? Clearly, one needs to do the basic homework well. Rigorous due diligence is a must. But for all those cases where the conducted due diligence did not identify the problems that were later discovered, that by itself is its own problem. For sure, these companies would have hired management consulting firms or auditing companies (and I am sure these are world-renowned brands) to do the due diligence and yet they couldn’t uncover some of the most basic yet critical problems. The reason behind this issue is that it really requires someone who understands the nitty gritty of businesses in China to do a proper and thorough job. This sort of capabilities is still rare in the professional firms in China especially those who are not headquartered in China.

Foreign MNCs shouldn’t assume that “integration” is the only way to capture the value of their acquisitions in China. At least, not “integration as fast as possible.” While in some cases integration may make sense, in many other cases, it may not. It depends on the contextual factors I mentioned above and the severity of the gaps in behavior and perspectives between the two sides. Due diligence should not only cover the “data” per se but also the culture, behavior and beliefs. This won’t be easy especially for many foreign MNCs. They tend to assign their M&A team from global HQ to carry out these tasks. While these people are usually technically sound and experienced with many deals under their belt, they often lack the experience and sensitivity needed to understand the softer, often unspoken, elements especially in a culture and context that are very different and can be overwhelming. Almost certainly, they don’t fully understand nor appreciate the China context. Over-eagerness in creating value often backfires as well as simple notions such as shared services, while a proven approach for realizing value in M&A deals in many parts of the world, may or may not achieve the same level of impact in China due to China’s complicity and diversity in labor rates, local regulations and requirements, as well as availability of competent human capital in key functions.

Fundamentally, MNCs need to fully evaluate the tradeoff between immediate integration or keeping companies separated or a gradual migration from separation to integration, and the speed and intensity associated with the process. Immediate and full-scale integration, which is often MNCs’ incoming assumption, may or may not actually yield the best result. Sometimes overzealous attempts at integration could result in loss opportunities for the MNCs to learn from the Chinese companies on how better to run businesses in China. For example, some Chinese companies are good at keeping their costs at manageable levels, while foreign MNCs tend to somewhat “gold-plate” things. For some local companies, their relationship with their distributors is often more win-win and intimate, while their foreign MNC counterparts can be more transactional.

Making the decision on integration or not correctly, and the manner of how, requires senior executives who can see the forest beyond the trees within the China context and increasingly, the role of China in the rest of the world, as well as being able to align the China realities with the expectation of the global headquarter. This capability does not always exist in MNCs but when it does, it’s a rare asset to have and to cherish.

About the authors

Dr. Edward Tse is founder and CEO of Gao Feng Advisory Company. A pioneer in China’s management consulting industry, Dr. Tse built and ran the Greater China operations of two leading international management consulting firms for a period of 20 years. He has consulted to hundreds of companies – both headquartered in and outside of China – on all critical aspects of business in China and China for the world. He also consulted to the Chinese government on strategies, state-owned enterprise reform and Chinese companies going overseas. He is the author of over 200 articles and four books including both award-winning The China Strategy (2010) and China’s Disruptors (2015) (Chinese version «创业家精神»).

Email: edward.tse@gaofengadv.com