Edward Tse

South China Morning Post 2016-02-23

One of the most talked-about topics these days is undoubtedly China. Is the country going to have a “hard landing”, as George Soros has proclaimed, or will it continue its transition to stability andprosperity?

Of course, numerous people have expressed their views on China over the years and these views cover the entire spectrum, from hugely negative to widely optimistic. For such a big and complex country, to expect smooth sailing all the way when it tries to reform itself is pretty naive. The world’s most populous country has a long history and civilisation but only a relatively short, though influential, period of a planned economy; its transition to a market economy is a complicated process, to say the least. Anyone can poke into China’s transition at any given point in time and find imperfections.

To start with, we must recognise the reality of what the Chinese government has done, lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty to a reasonable standard of living and enabling a significant degree of connectivity with the rest of the world. This, by any measure, is no mean feat.

People’s views on China will depend on who they are and, insome cases, their motives. A hedge fund speculator who has shorted China would, of course, propagate the view that the Chinese economy is going to crash or at least slow down. However, is this based on facts or merely a hope to maximise financial gains? In any case, these views tend to have a very short-term focus.

On the other hand, a chief executive of a multinational corporation would probably have a more balanced view of the short, medium and longer terms. It would be shaped by the experience he or she has had in China and the industry sector the company is in. If, for example, they run Home Depot, a US retail store whose business is built on customers’ “do it yourself” (DIY) habit, they would certainly be disappointed by China because Chinese don’t really “DIY”. Or, if their business is in China’s steel industry, which is suffering from excess capacity, they would probably concur that China’s short-term outlook is pretty gloomy.

For the past couple of decades, when China was growing at 9-10 percent every year, the tide was rising fast and as long as you jumped into the water, you would be carried upwards. Today, the tide is no longer rising as fast, though a 7 percent increase of the world’s second-largest economy still produces an annual increase the size of Switzerland’s gross domestic product.

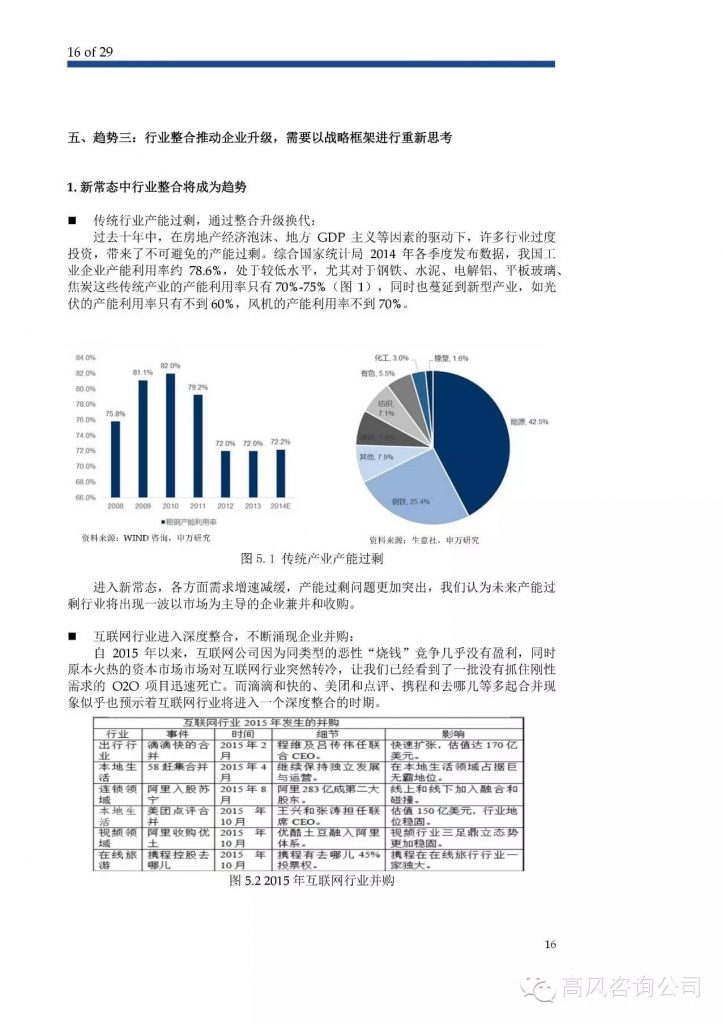

With a slowing tide,the diversity in China’s landscape has become more pronounced in several ways. Some parts of China are growing much faster than others, for one. According to government statistics, the western municipality of Chongqing grew by 11 percent last year while the northeastern province of Liaoning grew by a mere 3 percent. Sector divergence is also becoming more visible. Some sectors, such as steel and cement, are experiencing serious overcapacity while those revolving around China’s digital revolution, and the consumer and service industries, are generally doing well. Some sectors are being left behind as newer forms of technology are adopted.

The type of company could also make a difference. Large state-owned enterprises continue to enjoy some policy advantages; however, as technology and other enablers kick in, more sectors are opening up (intentionally or unintentionally) and large state-owned firms have found it increasingly difficult to outpace their competitors.

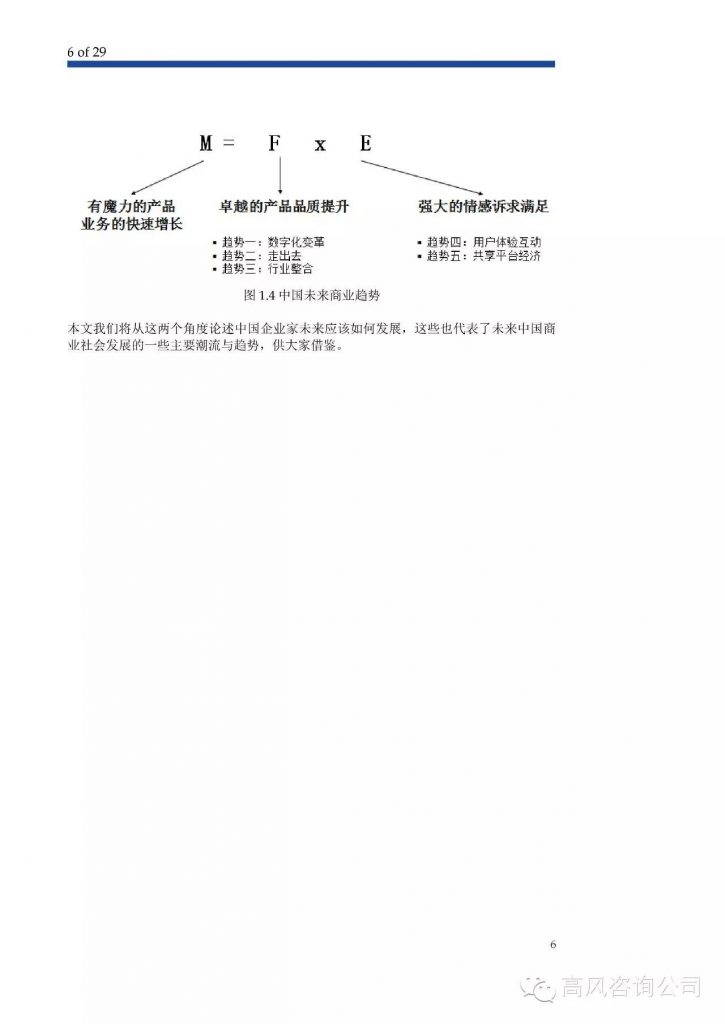

By contrast, many private companies are leveraging their nimble, agile and entrepreneurial ways to gain competitive advantages. Pockets of opportunities are popping up in China, even in the midst of a slowing tide. Urbanisation, technological upgrades in manufacturing, environmental improvements, the service economy and the internet will be key drivers of growth opportunities.

In 2015, China’s box office sales reached US$6.3 billion, making it the second-largest film marketin the world. Chinese travellers spent US$184 billion abroad, making them one of the largest tourist segments globally by spending. China has become the world’s largest robotics market, with purchases making up 25 percent of the global total. The on-demand mobility app Didi Chuxing totalled 1.43 billionrides in 2015 alone, in contrast to Uber, which took six years to hit 1 billion rides worldwide.

And, to top it off, global acquisitions by Chinese companies totalled nearly US$1 trillion. Perhaps in recognition of these pockets, foreign direct investment into China continued to rise in 2015 and multinational corporations’ confidence didn’t seem to dwindle much.

China’s service sector has already exceeded 50 percent of the country’s total GDP. The size of China’s middle class is significant. Depending on calculations, it is now anywhere between 150 million and 250 million people, or more. And all estimatesare projecting further growth.

Importantly, with more exposure, Chinese people are increasingly interconnected with the rest of the world. Social media such as WeChat, Weibo and LinkedIn (and, for those who can climb over the “Great Firewall”, Facebook and Twitter) ensure that the information they receive from China and the rest of the world can be received “anywhere, anytime”.

And, of course, the Chinese development model, which is built on a combination of the government’s “visible hand” and bottom-up entrepreneurship, continues to function in its ownway. This model, which created the so-called “China miracle” over the past 20 years, also has many issues. The model is likely to change, given China’s transition, but its effectiveness – as well as its problems – will continue to reveal themselves.

So here we are. A big and influential China will continue to evolve in its own way, well, with Chinese characteristics. The path forward won’t be perfectly smooth, but it won’t be doomed, either. The immense diversity of the country is both an issue and a major source of resilience.

It’s very easy for people to focus on China’s problems but they should also appreciate the immense progress it is making. To fully understand what’s happening, a more sophisticated view is needed.

Edward Tse is founder and CEO of Gao Feng Advisory Company, a strategy and management consulting company, and author of “China’s Disruptors” (Portfolio, 2015).