By Edward Tse | China Daily Africa | Updated: 2018-10-12

Working paradigm of nation’s economy has enabled robust momentum in driving progress and generating significant resilience

On Sept 27, during a visit to Liaoyang in Northeast China’s Liaoning province, President Xi Jinping stressed that China’s State-owned enterprises should continue to grow and develop. He added that the principle of having the Communist Party of China guiding the SOEs must be consistently followed.

On another occasion on the same trip, Xi stressed that, since the start of market reform and liberalization, the CPC Central Committee has always been supportive and protective of privately owned enterprises. China’s basic economic system must unwaveringly consolidate and develop the public sector, and unwaveringly encourage, support, guide and protect the development of the nonpublic sector, he said.

Are these stances regarding SOEs and privately owned enterprises contradictory to each other? How should we interpret the dual support by Xi for both types of enterprises?

The past 40 years of reform and liberalization have brought incredible changes and progress to China, turning the image of the country upside down, from a planned economy to one of the world’s most dynamic business landscapes.

Along the way, China has evolved its own development path, without consciously knowing it. At the top, the central government’s guiding hand sets goals and directions for the country, giving the rest of the country clear targets to follow. At the grassroots level, private-sector entrepreneurs have re-emerged and become a major force in driving not only the growth of China but also of the global economy. In the middle, China’s local governments, in response to the central government’s direction and strategy, channel their resources and focus on areas of national and local priorities. The local governments often collaborate closely with entrepreneurs who bring innovative ideas to bear. Local governments compete with each other as well as cooperate to form regional clusters. A good example is the Greater Bay Area, which consists of nine cities in Guangdong province, including Shenzhen and Guangzhou, as well as the special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macao.

This three-layer working paradigm, while evolving, has enabled robust momentum in driving progress forward and generating significant resilience. Between 1978 and 2016, China’s annual GDP growth averaged 9.7 percent, faster than the growth of any other country over the same period and almost quadrupling that of the United States.

The symbiosis of SOEs and privately owned enterprises, in China’s dual economy structure, is a defining feature. SOEs take initiatives on the country’s mission-critical projects such as major infrastructure, utilities, natural resources, military and defense. Within a decade, for example, China was able to build the world’s most extensive high-speed railway network from virtually nothing, thanks to its SOEs – a feat that would probably not have been possible if left to the private sector. On the other hand, privately owned enterprises are great at market-driven innovations, often enabled by technology that addresses society’s pain points. While SOEs in many cases enjoy greater advantages in terms of policy privileges, resources and capital, and licensing rights, privately owned enterprises embody more speedy organizations, higher business innovation potential and more sensibility and adaptability to market changes.

Though the dual economic structure encounters occasional glitches with inherent conflicts at times – on many occasions, pundits asserted “guo jin min tui”, meaning “the state advances while the private sector retreats”, while other pundits asserted the opposite – the two sides of the economy for the most part complement each other, often without knowing it, as each takes on its respective role.

China’s entrepreneurs have evolved in generations. In the late 1970s, at the end of the “cultural revolution” (1966-76), the underdevelopment of the Chinese economy spurred a new sense of purpose among China’s newly emerged entrepreneurs – the desire to strive for success and to show the world that they, too, could succeed. Even today, this notion of “Why not me?” is still the key motivator that drives the Chinese entrepreneurial spirit.

Source: Internet

Today, younger generations of entrepreneurs continue to inject vigor into the country, and they are also more geographically diverse. China Youth Daily reported in 2016 that the age of first-time young entrepreneurs in China averaged around 25; another study found that although startups generally prefer top-tier cities, they are also reaching lower-tier cities such as Xi’an and Qingdao.

An earlier article in South China Morning Post said that the scale and influence of China’s private economy can be recapitulated by “56789” – contributing 50 percent of tax revenue, 60 percent of gross domestic product, 70 percent of industrial upgrades and innovation, 80 percent of total employment and 90 percent of the total number of enterprises.

With President Xi’s declared goal of creating an innovation nation by 2030, we will expect more innovations to come from China. The country is now already the second-largest spender on research and development and accounts for 21 percent of the world’s total, according to the US National Science Foundation. The World Intellectual Property Organization reported that China contributed to 98 percent of global growth in patent filings, more than the combined total of the US, Japan, South Korea and Europe.

The Chinese are fully embracing new and emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, the internet of things, blockchain and 5G to further enable innovations. The three-layers paradigm continues to manifest itself. Governments at central and local levels alike, as well as the private sector, are investing significantly in revolutionary fields. These technological breakthroughs will enable a higher level of automation, connectivity and intelligence, and will enable more game-changing business models.

Source: Internet

Recent research from Tsinghua University found that two-thirds of global investment in AI is going to China, enabling a 67 percent growth in the industry in just the past year. A report by ABI Research says that Chinese AI startups have already overtaken their US counterparts by raising nearly $5 billion (4.3 billion euros; £3.8 billion) in venture capital funding in 2017. In November, Shanghai announced a new plan outlining a road map toward becoming a major national AI hub.

Around 450 blockchain technology companies have been registered in China, according to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. The regulatory attitude toward blockchain has turned from skepticism to acceptance and now to support. Throughout this year, the Chinese government has funded multibillion-dollar initiatives to develop blockchain-based networks, with Hangzhou’s city government investing a total of $1.6 billion in the Global Blockchain Innovation Fund in April.

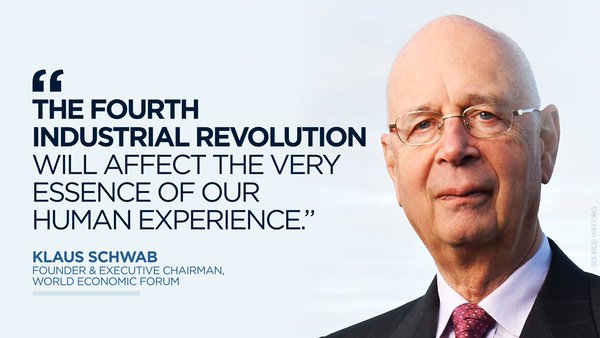

China will be in the front seat witnessing the turning point to the Fourth Industrial Revolution, characterized by cutting-edge technologies that are blurring the lines between the physical, digital and biological spheres, perhaps ahead of most of, but not all, other countries in the world. As the country continues to embrace multilateralism, naturally it will play an even larger and more responsible role in future global governance.

We expect China to step up further and take on more global leadership in an increasingly turbulent and uncertain world, and even more and disruptive innovations to come from China’s businesses through a unique, three-part duality construct.

The author is founder and CEO of Gao Feng Advisory Co, a global strategy and management consultancy with roots in China, and author of China’s Disruptors. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.