Preface

Over the years, perspectives on China have run the gamut from predicting “the coming collapse of China” to expecting that “the twenty-first century will be the Chinese Century.” And we’ve heard every perspective in between.

Despite its many ups and downs, the Chinese economy has grown significantly over the past several decades. While at any given point in time one could point to China’s many problems and risks, China has, as a whole, exhibited an extraordinary level of resilience. Why is that and how does China do it?

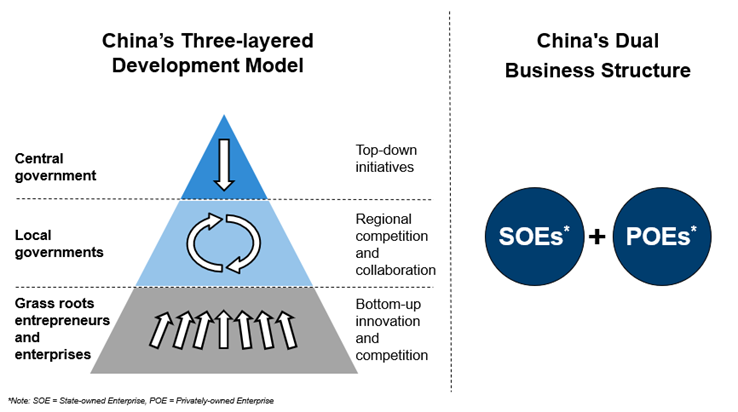

In this article, I take my best shot at summarizing the three primary reasons for China’s resilience: A composite “three-layered duality” structure; a pragmatic approach of experimentation, learning and adaptation; and a set of highly sophisticated large-scale coordination and organizational capabilities.

These three approaches are the direct result of the way modern China has evolved and developed over the past two hundred years. As Chinese intellectuals reflected on how China could modernize itself, they would often draw upon China’s vast reservoir of history, culture, and civilization. At the same time, they would take into account newer concepts – which often originated from the West – as well as the realities of our changing world, in their search for Chinese-style modernization and modernity with Chinese characteristics.

I hope that my perspective will be helpful and instructive for executives of global companies who are now evaluating what role China will play in their businesses in the coming years. Developing a company’s global strategy – which, by definition, includes a China strategy – requires a deep understanding of China’s evolving role in the new world, a basic knowledge of the fundamental reasons why and how China works, and a clear-eyed view of the implications of the new dynamics of competition and collaboration given China’s role in the world.

THE FUNDAMENTAL FACTORS ARE CLEAR AND CONSISTENT, BUT ARTICULATING THEM REQUIRES SOPHISTICATION

Ever since China’s reform and opening up began, the nation’s growth has impressed and surprised a lot of people. Many of them have tried to explain why China has been able to grow so fast and how it has been able to exhibit such a high level of resilience. Some commentators have suggested that the Chinese government controlled everything in the country, including each and every single step of the various enterprises and their people. These commentators typically – and falsely – equated today’s China with the former Soviet Union. Among these critics, some would chatter on about, “the coming collapse of China” or say “China has peaked.” At the same time, others would say that China would ultimately fully embrace capitalism and that the Chinese would become “just like us.”

I cannot say whether these narratives are entirely right or wrong. However, they certainly do not explain the real fundamentals of why China has been able to achieve so much within such a short span of time. Even in this “Era of Mega Changes” China has continued to exhibit high levels of resilience. Let’s explore some of the actual reasons for China’s sustained growth.

“THREE-LAYERED DUALITY”

Since 1840, generations of Chinese intellectuals have been searching for ways that China could revitalize itself. This soul-searching process has accelerated since the country’s reform and opening up in the early 1980s. This process included many cycles of experimentation, learning and adaptation during which the Chinese repeatedly absorbed new ideas against the backdrop of the country’s ancient and long history, culture, and civilization. While the Chinese leaders embraced fundamental beliefs such as socialism and traditional Chinese culture, they also accepted new ideas such as a market economy and globalization. This type of inclusive and adaptive approach against a specific historical backdrop created a development mechanism that underwent repeated adjustments and, along the way, led to optimization. As a result, “socialism with Chinese characteristics” emerged, evolved, and continues to evolve to this day.

More specifically, China’s governance system features a “three-layered duality” structure. The central government provides the overall development direction for the country, as well as specific strategies and policies. Unlike the former Soviet Union, the Chinese government – post-reform and opening up – would not specifically dictate goals for Chinese enterprises but would merely provide broad direction and suggestions for the development of the entire nation. Of course, the government would have expectations for their state-owned enterprises (SOEs) whose role is to (at least partially) fulfill certain social responsibilities. However, for the privately-owned enterprises (POEs), the government would not and, in fact, cannot dictate operating targets.

Exhibit 1: China’s “Three-Layered Duality” Structure

Source: Gao Feng analysis

One of the most dramatic developments in China since its reform and opening up has been the rapid development of the private sector. Today, many of the most successful companies in China are private-sector enterprises. On the other hand, SOEs play a critical and dominant role in industries such as banking, telecommunications, aviation, railways, and energy. Enterprises, especially POEs, often get cues from the central government’s policies. They react quickly and are often able to take advantage of the opportunities brought about by the new government policies.

Resourceful and capable local governments would often play an important role in serving as a connection between the central government’s policies and the enterprises, both those that are state-owned (SOEs) and those that are privately-owned (POEs). These local governments would provide funding and other forms of support to qualified and interested companies. Local governments would help to incubate start-ups and help connect them with players both upstream and downstream of the companies’ value chains, including potential customers. For more mature companies, local governments would provide even broader support through the government’s ecosystem.

China’s dual economic structure of SOEs and POEs provides both benefits and downsides. In addition to their financial responsibilities, SOEs must often fulfill social obligations. For example, they provide most of China’s essential public goods.

The most classic case is China’s high-speed railways or HSR. Within slightly over a decade, China went from having no HSR to having the world’s most extensive (and high-quality) 42,000-kilometer HSR system. Without the SOEs, one would be hard-pressed to imagine how this system could be built at such speed and magnitude. If an HSR project were to be undertaken by POEs, its financial feasibility would not likely pass the typical financial hurdles. However, from an SOE standpoint, it would view such a project from a more macro and long-term perspective. In addition to considerations of short-term financial returns, SOEs would also need to consider social contributions and financial benefits at a broader level.

Exhibit 2: China’sHigh-speed Railways Network, 2010 vs. 2023

Source: Internet

Another notable example is China’s metro (urban rail transit) system. As of the end of 2022,urban rail transit systems are operational in 52 cities throughout the Chinese mainland, comprising a total length of 10,288 kilometers of operating lines. This achievement makes China’s urban rail transit network the largest in the world [1]. While it took China 38 years to reach the first 1,000 kilometers of operational urban rail transit, the second 1,000 kilometers was achieved in less than five years. Measured by the annual growth rate of the total length, China is also significantly ahead of the rest of the world with a double-digit growth rate. In comparison, the rest of the world’s urban rail transit grew at a rate of 2.5%-4.5% over the same period.

The rapid expansion of the metro system in China is primarily due to the government’s decision to prioritize the development of the urban transportation network. SOEs participate in the metro system’s investment, construction, operation, and management. It is part of the social responsibility of the SOEs which actively assist the local governments in delivering public goods to their residents.

The construction of 5G base stations is another good example. As early as in 2015, just one year after the commercialization of 4G in China, the government announced a plan of “striving to commercialize 5G by 2020.” On the one hand, major Chinese telecom SOEs – China Mobile, China Unicom, and China Telecom – were actively prepared to build the 5G base stations. On the other hand, private sector companies like Huawei and Zhongxing Telecommunication Equipment Company (ZTE) made significant investments in the research and development (R&D) of 5G infrastructure equipment such as antennas and radio frequency devices. As of the end of March 2023, 2.384 million 5G base stations were built in China – accounting for over 60% of the world’s total – serving over 590 million subscribers in China, with many base stations located in remote areas. While building out so many base stations may not make sense in the short-term financially, SOEs would nonetheless build them as part of their social responsibility.

In other words, the development of China’s 5G network, from the R&D of fundamental components to the nationwide deployment of base stations, relied heavily on the backing of both SOEs and POEs along with the government. Together, they proactively addressed the current national development requirements and fulfilled their social responsibilities while generating long-term financial benefits.

Of course, there is often friction between SOEs and POEs, especially when they compete in the same sector. Ensuring fair competition in these cases is critical. All along, some commentators would say, “state advances while the private sector retreats,” while others would say “POEs do a much better job than SOEs in sectors such as the internet.” While some of these narratives are not necessarily untrue, China’s “dual economic structure” as a whole is extremely effective, particularly when one considers China’s development from an overall, long-term perspective.

The three-layered structure consisting of the central government, local governments, and businesses, in combination with a dual economic structure comprised of both SOEs and POEs, creates a multi-dimensional “three-layered duality” structure. While this structure may sound complicated at first, it is actually quite simple and effective. Governance of such a large and multi-faceted polity requires coordination and dynamic, real-time adjustments. To accomplish this, strong leadership-driven large-scale cooperation and organizational capabilities are essential. At the beginning of the reform and opening up period, Chinese leaders did not have a clear and complete blueprint for development. Hence, an approach that involved rounds of experimentation, learning and adaptation became the underlying mechanism for continuous adjustment and optimization.

EXPERIMENTATION, LEARNING AND ADAPTATION

Since 1842, generations of Chinese intellectuals have undertaken rounds of study and reflection to determine how to rejuvenate the Chinese nation. They drew inspiration from Chinese history, culture, civilization, and ideas from the West. These elites studied, collectively reflected, and discussed and, ultimately, they came up with their own new and innovative ideas.

Since its reform and opening up, Chinese leaders have likewise adopted an approach of cycles of experimentation, learning, and adaptation to search for ways in which China could most effectively develop.

Four cities – Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou, and Xiamen – were assigned Special Economic Zone (SEZ) status in the early stages of the reform and opening up. These cities could offer more open policies to attract foreign capital and talent than the rest of the country. These cities were allowed and encouraged “to be bold” in experimenting with new ideas and policies that the rest of China could not.

Many favorable policies were implemented in the SEZs. For instance, companies in an SEZ could benefit from preferential tax rates on corporate income, equipment, raw material imports, and product exports. Other policies included foreign exchange settlement and remittance, land access, as well as entry and exit procedures. Serving as gateways for international exchange, SEZs leveraged their policy and location advantages to achieve significantly higher growth rates than other regions in China.

Exhibit 3: Portrait of Deng Xiaoping on Shennan Avenue in Shenzhen (left), First Five Special Economic Zones in China (right)

Source: Internet, Gao Feng analysis

In fact, whenever there were any major new initiatives, China would conduct pilots before launching the initiatives at full scale. The SEZ initiative, launched by Deng Xiaoping, is one of the most well-known examples. After the first successful batch of pilot cities provided valuable experiences and insights, the Chinese government designated Hainan province as another SEZ in 1988. This designation followed the establishment of 12 “Comprehensive Reform Pilot Zones,” also known as “New Special Economic Zones,” which included the Shanghai Pudong and Tianjin Binhai areas. Additionally, five “Financial Pilot Zones” were established, including Wenzhou City in Zhejiang Province, the Pearl River Delta Region in Guangdong Province, Quanzhou City in Fujian Province, Guangxi Province, and Qingdao City in Shandong Province.

During the 1990s and early 2000s, the most talked-about phrase in China was probably “(How China could) align with international practices.” This summarized China’s desire to understand and follow international rules and best practices. “Aligning with international practices” pertained to a wide range of areas, such as development models, policies, and regulations. It reflects China’s desire to integrate into the rest of the world.

The Chinese would benchmark practices and experiences from other countries or jurisdictions. China’s learning targets began with Hong Kong, then moved on to Singapore and Taiwan, followed by Japan and Korea, and finally extended to the West and the rest of the world. Before implementing important policies in areas such as finance, healthcare, social welfare, and industry development, the Chinese government would study the practices and experiences of a range of countries and jurisdictions, comparing and contrasting these approaches. Based on their analysis, the Chinese government would decide on the best strategies for China.

As a reform mechanism, pilot programs are still being undertaken today. The Chinese government (and enterprises) can gain insights and make appropriate adjustments through pilots. For example, in May 2023, Zhejiang Province held its first Pilot Promotion Conference for Common Prosperity. The conference reviewed how Zhejiang Province progressively implemented pilots in stages for achieving common prosperity, using the central government’s “pilot within a pilot” approach. Although there are no similar precedents that Zhejiang can follow, this approach could become very effective and have a nationwide impact.

Today, the implementation of China’s central bank digital currency (e-CNY) is progressing across China. Tailored e-CNY payment solutions are being developed and tested within some pilot regions, such as Jiangsu Province, Shenzhen City in Guangdong Province, and Yiwu City in Zhejiang Province, for various application scenarios. China aims to integrate the e-CNY into people’s daily lives step by step by piloting it under various scenarios, such as digital red packets for shopping incentives, purchasing and redeeming sports lotteries, digital wallets that offer a new payment experience to expatriates, and cross-border transactions under the consensus of different countries’ central banks.

Pilot programs have played a significant role in many respects as an essential approach to China’s reform and opening up. First, they can test the effectiveness of new systems or policies within a limited range and provide invaluable experience to guide full-scale rollouts. Second, they can reduce potential resistance to changes and increase acceptability and flexibility. Third, they can take full advantage of the spirit of innovation at the local and grassroots levels, ensuring that reform aligns with local conditions. Fourth, they can avoid a one-size-fits-all approach and reduce the risks and costs of reform. Finally, they can improve the efficiency and quality of reform, further driving improvements and development.

LARGE-SCALE ORGANIZATIONAL CAPABILITIES

The execution of the “three-layered duality” approach requires significant coordination and organizational capabilities. Although Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the chief architect of modern China’s efforts to overthrow the Qing dynasty in the early 1900s, once said, “The Chinese are like a batch of loose sand,” (meaning the Chinese did not work together). Although not perfect, China’s several millennia-long governance systems – a mix of Confucianism and Legalism – were quite effective in governing a vast territory which included a large, complex and diverse population.

Since the foundation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the Chinese government has initiated a strong overall organizational structure across the entire nation. Managing this tight and vast structure requires strong organizational capabilities. According to the PRC’s constitution, the country is organized into three levels of administrative divisions: provinces (which include autonomous regions and municipalities), counties (comprising cities and autonomous counties), and towns (including villages and streets). These undertaking-specific management divisions form the basic units of governance in China. The central government leads all these units while the local governments provide day-to-day administration.

The Chinese government uses a Hukou system, also known as a household registration system. Through this system, the Chinese government maintains data on where people’s primary residence is located and this data is used to administer social services and government benefits based on the official Hukou location. As a centrally-controlled hierarchy with a broad and detailed administrative structure across all of China, the Chinese government’s ability to organize and mobilize resources at a large scale has become a standout feature of the PRC.

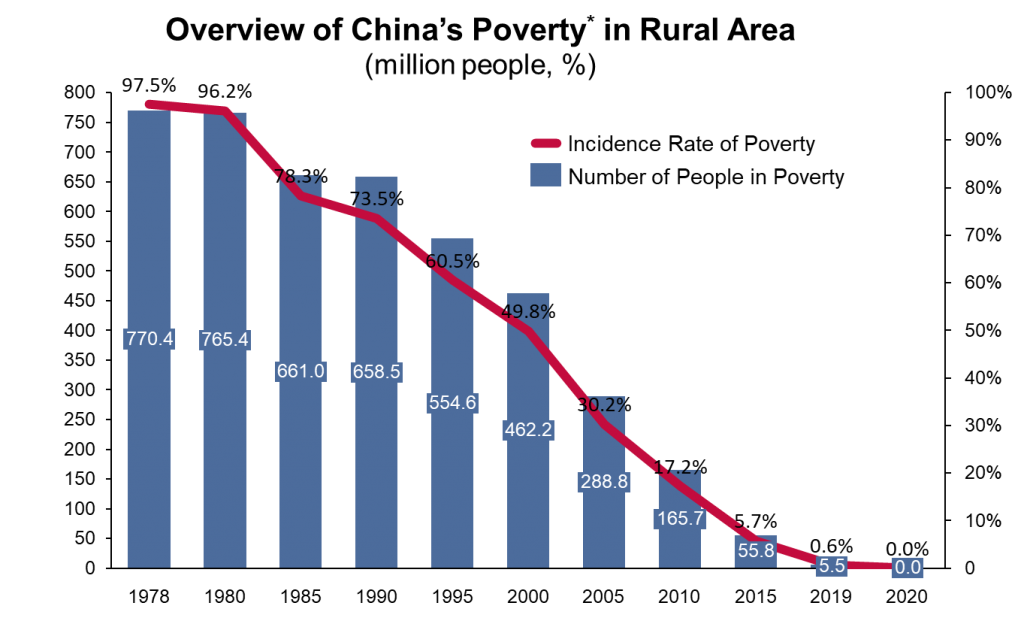

China’s massive poverty alleviation endeavor exemplifies its strong large-scale organizational capabilities, as evidenced by the remarkable transformation of Jinzhai County, Anhui Province. In 2014, approximately 40,000 households with 130,000 individuals were registered as impoverished families in Jinzhai, accounting for 22.1% of the total population. Since the poverty alleviation campaign started in 2016, all 130,000 individuals across 71 poverty-stricken villages in Jinzhai were lifted out of poverty within just four years [2]. Consequently, Jinzhai was taken off of China’s list of poverty-stricken counties. Such extraordinary success didn’t happen by luck.

This remarkable feat required meticulous planning and execution. It began by conducting a nationwide census to identify and register all impoverished citizens, establishing clear targets and safeguarding against corruption. Grassroots poverty alleviation teams were mobilized by provincial and local governments, with each village that had a poverty household receiving assigned secretaries and resident working groups. By 2020, over 255,000 resident teams and 3 million officials had been dispatched across China. Aside from sending permanent officials, the government instituted a “Paired-up Assistance System,” assigning designated poverty alleviation helpers to each household with personalized and targeted intervention plans, strictly implemented in accordance with poverty alleviation manuals from the State Council (Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development). These paired-up helpers were rotated annually and evaluated after each term to ensure accountability. In addition, the government also mobilized SOEs, POEs, and local PLA (military) to contribute through donations, purchasing agricultural goods from impoverished families, and providing job opportunities if needed.

Since China’s reform and opening up, over 770 million people have been lifted from poverty. Rhetoric alone cannot achieve such a massive and effective decades-long program. Rather, it is China’s large-scale organizational capabilities and institutional strength that enabled this historical achievement which has earned China respect around the world.

Exhibit 4: China’sPoverty Reduction in Rural Areas, 1978-2020

*Note: Defined as annual income below RMB 2,300 per capita in a household (Set by the National Bureau of Statistics of PRC in 2010)

Source: Xinhua News Agency, Gao Feng analysis

Such a large-scale organizational capability is often called a “whole-of-nation approach.” This means that when the Chinese government aims to achieve something of scale and significance, it can and will mobilize large-scale, nationwide resources and capabilities to get the job done. The poverty alleviation initiative is just one of many examples. Other major initiatives, such as the South-to-North Water Diversion Project, the anti-desertification effort, and the goal of carbon neutrality by 2060, also require the sustained mobilization of large-scale resources.

In the podcast China Corner Office produced by The China Project, Apple University Professor Doug Guthrie stated, “Apple has a significant market in China, as does Tesla and other companies. But what makes these companies so powerful is their management of the supply chain.” [3] However, as Doug pointed out, the capability of supply chain management relies on the advantageous features of China and its government (both central and local) and SOEs. First, China has access to a massive migrant labor force of 350 million workers that can rapidly scale up or down through the government-controlled labor dispatch system. Second, extensive integrated transportation infrastructure efficiently connects raw material suppliers, component manufacturers, assembly factories, and logistics networks, enabling responsive and nimble manufacturing ecosystems. Finally, China has strategically created industry clusters in certain cities and regions, such as the automotive manufacturing cluster in Guangzhou, which promote specialization, knowledge sharing, and tight supplier integration.

The combination of a flexible labor force, integrated infrastructure, and industry clustering provides China with a unique manufacturing process that underpins the success of many foreign firms operating there, including Apple.

A large number of suppliers, including those from China and other countries and regions, rely on the supply chain ecosystem and infrastructure that have been developed over time. The Chinese government and SOEs played a significant role in providing the necessary public goods. Additionally, the local governments were particularly instrumental in working with the suppliers and manufacturers to mobilize labor to work in these ecosystems. The efficient and dynamic management and coordination of this supply chain ecosystem and infrastructure enables the highly efficient nature of Apple’s supply chain.

In simple terms, China also adopts a “whole-of-nation approach” to support Apple’s supply chain development. As it builds out its supply chain in China, Apple is looking not only for low labor costs but also other benefits that are generated from the coordination and organization that the Chinese government, particularly local governments, can drive and deliver. In addition, the numerous suppliers, primarily Chinese, involved in these complex supplier ecosystems would naturally find ways to synchronize with the orchestration by Apple and the leading manufacturers and local governments.

Professor Guthrie also emphasized that “no intellectual property theft” occurred at Apple in China: “In today’s era…the real IP is around manufacturing processes… Apple will never set up a factory in China. What they did was they took their employees, who are brilliant people in operation supply chain management, and they embedded them in the factories of China’s suppliers. They teach, and everybody learns together. And so, it’s hard for me to think about this as some commentators think about this as stealing IP – I don’t think it’s stealing IP. These are collaborative relationships in which people learn together.” [3]

Professor Guthrie believed Apple and its Chinese suppliers developed the necessary intellectual property in a collaborative manner. Guided by a spirit of collective cooperation, suppliers, regardless of their origin, can consistently assist Apple’s highly efficient supply chain with innovations facilitated through the provision of public goods by the Chinese government and SOEs. This is made possible through meticulous and extensive coordination at all times.

A COMPOSITE PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP

China’s economy is neither a market economy nor a planned economy but, rather, it is a combination of both. SOEs, POEs (both local and foreign), local governments and central government, all play critical roles in China’s unique economy. For Chinese companies, particularly the POEs, the government does not allocate planned resources and performance targets. Instead, enterprises drive their own business based on the central government’s policies, entrepreneurship, equity reform, market competition and innovation, often with support from their local governments. The diverse stakeholders in China’s mixed economic model leverage their respective strengths while aligning with national priorities through a collaborative approach.

The Chinese local governments play a crucial role in driving public-private partnerships. Many local governments are well-positioned to support businesses today as they have come a long way economically over the last several decades. Cities such as Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Beijing, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Suzhou, Wuxi, Nanjing, Tianjin, and Chongqing, among many others, are all well-known for supporting businesses. Among these, Hefei City in Anhui Province stands out as a notable example.

Hefei’s Experience

Situated strategically between the Yangtze and Huai Rivers, Hefei, the capital of Anhui province in Eastern China, has long played a pivotal role in regional administration, economy, and military affairs throughout history. With its advantageous geography, Hefei emerged as a critical hub for trade and transport. Today, the city is recognized as a thriving technology and economic center in China’s central and eastern regions.

Often called the “Hefei Model,” the city’s developmental approach leverages state-owned enterprises and academic institutions to establish industry-focused investment funds. Through direct investments and active participation in various funds, the government drives the infusion of private capital to foster business expansion. This model, predicated on judiciously directing investments into priority sectors, has proven effective in driving Hefei’s economic development and has benefited many businesses along the way.

Exhibit 5: Geographic location of Hefei, BOE, Lenovo and Compal Future Center (LCFC), and NIO Parks in Hefei

Source: Internet, Gao Feng analysis

A key factor in Hefei’s success is how the region work’s with business. Despite government shareholding, companies maintain a degree of autonomy and managerial control. This allows the companies to run their business in their own way but, at the same time, they can also leverage support that the government provides. Through this approach, Hefei has excelled in strategic sectors, including new-generation display devices, integrated circuits, artificial intelligence, and new energy vehicles.

Furthermore, Hefei embraces the mindset of venture capital and investment banks. Their investment funds would recruit industry experts and seasoned advisors for meticulous evaluation of opportunities. Investments are rigorously assessed for technology, supply chains and market potential. The ability to generate ecosystem synergies is also critical. Ongoing support provided by various governmental departments ensures these synergies can be materialized. As a result, Hefei attracts both established players and emerging innovators and, along the way, they form a robust ecosystem.

To ensure a proper focus and capability boundaries for selected sectors, Hefei pioneered the “Chain Chief” notion, designating senior government officials who are responsible for optimizing industrial chain development plans and policies. This initiative includes cultivating key companies, facilitating pivotal projects, and establishing service platforms and mechanisms for regular services. Coordinating resources across industrial chains through these “Chain Chief” positions supports accountability for value chain integrity and progression.

Moreover, Hefei propagates a business-friendly environment underscored by innovation and service. Augmented by robust industry support and technological incentives, this milieu has magnetized numerous companies. Notable illustrations include BOE, a leading Chinese semiconductor and display device manufacturer; Lenovo, a global information and computer technology (ICT) player, and; NIO, a well-known Chinese electric vehicle brand.

The first case is BOE. In 2008, BOE, a leading Chinese semiconductor and display device manufacturer, planned a landmark US$2.5 billion investment to construct a 6th generation Liquid-crystal display (LCD) production line in Hefei. At the time, Hefei’s entire fiscal revenue was only around US$2.3 billion [4]. Despite substantial economic and political risks, Hefei decided to support this ambitious project.

Per their agreement, Hefei committed US$900 million in direct investment along with US$1.2 billion in conditional loan guarantees, contingent upon attracting co-investors. This public-private collaboration aimed to catalyze industrial upgrading. BOE has since invested over US$15 billion in Hefei, creating 20,000 jobs and US$6 billion in annual revenue. BOE built an integrated, efficient R&D and manufacturing base by leveraging Hefei’s strategic location and talent pipeline. This has enhanced BOE’s overall competitiveness and innovative capacity, cementing Hefei as a global display production hub.

The second case is Lenovo, one of the world’s largest ICT giants. In 2011, Lenovo partnered to construct a Hefei laptop factory, Compal, increasing annual production capacity forty-fold to 40 million units in six years [5], and it is presently the world’s largest laptop plant.

Following the initiation of production, Lenovo contributed up to 40% of BOE’s display screen capacity in the initial years while sustaining BOE’s development by incorporating 5% of its laptops with BOE’s new-generation display screens. To cultivate an integrated value chain, Hefei attracted over 300 suppliers, including 20 public firms, thereby incubating an innovative ICT cluster. The government provides incentives, such as tax relief, to facilitate Lenovo’s continuous expansion. Furthermore, Hefei’s partnership with Lenovo exemplifies a sophisticated orchestration of synergies across companies and sectors. Through proactive supplier recruitment, Hefei has nurtured an integrated ICT ecosystem. Continued support, including incentives and talent programs, further fortifies Lenovo’s position as an anchor tenant, underscoring Hefei’s adept capacity to incubate industrial champions and clusters.

The third example is NIO, a Chinese electric vehicle (EV) brand, one of China’s “New Force in EVs.” In 2016, NIO partnered with Jianghuai Automobile (JAC Motors) to utilize JAC’s Hefei production facilities, establishing an initial manufacturing base. In 2020, recognizing NIO’s economic potential, Hefei provided over US$1 billion in strategic investment to make NIO’s China headquarters and EV cluster in Hefei [6]. This collaboration had a real economic and social impact, further catalyzing other industry investments for NIO and Hefei. It supports the development of NIO and a smart EV industry cluster on the ground. Hefei’s investment and policy incentives turbo-charged NIO’s growth, transforming it from a nascent entity on the brink of bankruptcy into a prominent player in China’s electric vehicle industry. Examples like this demonstrate Hefei’s capacity to nurture emerging champions even amid periods of uncertainty. The ensuing cluster development and synergy exemplify the potential of the “Hefei Model”.

These three instances underscore Hefei’s adeptness at orchestrating synergies across sectors. Lenovo’s expansion spurred demand for BOE’s displays, thereby catalyzing the broader electronics cluster. With Lenovo and Compal Future Center (LCFC) contributing 10% of its GDP, Hefei could incubate emerging champions like NIO, revealing a significant capacity to leverage synergies.

Consequently, Hefei has cultivated advanced integrated circuits, new-generation displays, new energy vehicles, safety and emergency, smart devices, life science and health, and artificial intelligence sectors. Their nimble marshaling of resources has earned Hefei recognition as a highly-skilled quasi-venture investor.

BOE, Lenovo and NIO showcase Hefei’s sophistication in seizing opportunities to attract and build strategic industries. Hefei adeptly evolved sector clusters into fully-fledged industrial bases by attracting anchor companies and upgrading key industrial chains.

Additionally, effective administrative services and favorable policies are essential to Hefei’s business environment. This helps companies overcome capital, land and talent barriers and enables accelerated growth. Encouraged by the success of BOE, Lenovo, and NIO, Hefei upholds an “industrial value chain-oriented” investment mindset for guiding the development of its portfolio of investments. Furthermore, driven by a philosophy of investing and building up industrial value chains, Hefei sets up market-oriented funds to invest across supply networks, further catalyzing its development.

For example, leveraging extensive high-tech expertise, Hefei incubated ChangXin Memory Technologies (CXMT), an advanced semiconductor firm. Established in 2017 by GigaDevice and Hefei’s state-owned capital, CXMT announced mass production of DDR4 memory chips in 2019. In 2020, they raised RMB 15.6 billion [6] from strategic investors, including the National Integrated Circuit Industry Fund, making them a competitive leader in the domestic semiconductor and wafer manufacturing sectors, competing against the monopolies of international giants.

Hefei has achieved win-win scenarios with social and economic benefits through its investments along various industry chains, cross-industry-chain synergies, and the associated technological innovation and application of these areas.

The scope of the local government’s support is not limited to Chinese companies only. The Hefei municipal government also prioritized the attraction of leading global players for craving its key industrial chains. By attracting a substantial number of foreign companies, such as Volkswagen and Corning Glass, Hefei has effectively enhanced the international competitiveness of its industrial clusters. This showcases Hefei’s adept capacity to nurture national as well as international champions in critical technology arenas.

Leveraging its robust New Energy Vehicle (NEV) industry ecosystem and efficient governance, Hefei was able to attract Volkswagen, resulting in an investment of US$1.1 billion to build the company’s largest China R&D center in Hefei [7]. Moreover, Volkswagen has planned an additional investment of US$3.4 billion in Hefei’s NEV production and R&D. By choosing the NEV sector as one of its priorities, Hefei identified potential company targets, proactively reached out to them and aligned plans of investment on the ground. The access of its first investment would lead to others and would soon fill out the target sector’s industry chain and industry clusters.

Hefei demonstrates how a local government can effectively support businesses and help them to succeed, particularly those in the target strategic sectors. In addition to the anchor companies, clusters of suppliers can also help create stickiness of manufacturing in the locality.

Local Government’s Industrial Guidance Funds

The key role that local governments played, in particular, channeled through the government’s Industrial Guidance Fund, is vital for many businesses who moved their operations towards localization, which is also core to the “Hefei Model”.

The Venture Capital Guidance Fund (VCGF) is a type of Industrial Guidance Fund representing government-backed venture capital investors who typically strategically target specific industries, stages of development, and geographic regions. These entities, propelled by limited public funds, aim to attract private capital to bridge the financing needs of early-stage technology firms. By the end of 2022, Chinese governments had established over 1,500 VCGFs [8], with a total size of US$400 billion.

The significance of industrial guidance funds to local industries can be prominently exemplified by the VCGF of Shanghai, orchestrated by Shanghai Science and Technology Venture Capital. This fund strategically aligns with burgeoning sectors like new energy vehicles, biotechnology, and next-generation information technology. It boasts of investments in noteworthy enterprises such as Cmsemicon, a pioneer in mixed-signal chip design; Endovastec, a frontrunner in vascular interventional devices, and; Qihoo 360, a Chinese cybersecurity firm celebrated for its antivirus solutions.

In a similar vein, Guangzhou’s industrial guidance fund, with a capital of US$7 billion, champions high-tech arenas, including semiconductors and integrated circuits. This fund has been instrumental in fostering growth in companies like DarkMatter AI, creators of cognitive AI tools for education and health; GAC AION, a prominent EV subsidiary of Guangzhou Automobile Group (GAC), and; GRGBanking, a leading solution provider for the intelligent finance industry.

Shenzhen’s industrial guidance funds, oriented toward angel investments, emerged as the preeminent fund of its kind, directing its focus toward strategic sectors like semiconductors, new materials, and biopharmaceuticals. Its enviable achievements encompass the incubation of over 200 enterprises, including stalwarts like Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited (CATL) and Mindray, a global giant in medical equipment headquartered in Shenzhen.

In parallel, the industrial guidance fund of Suzhou has significantly propelled the growth trajectories of leading players like Bloomage Biotech, renowned for its specialization in aesthetic biotechnological solutions; Novosense Microelectronics, a premier producer of advanced semiconductors and integrated circuits, and; Gstarsoft, an expert in Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software development.

Industrial guidance funds exemplify how targeted government venture capital can effectively catalyze development in emerging strategic industries. By attracting private capital and addressing financing gaps, industrial guidance funds accelerate technology commercialization and cluster growth, fostering China’s industrial growth.

Unsuccessful Cases

While the general experience of local government support for businesses has been positive, instances of unsuccessful cases have also emerged.

Suntech, a prominent solar firm backed by the Wuxi government, was an illustrative case. Established in 2001 through a government partnership, Suntech experienced rapid growth, culminating in an IPO on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in 2005. That was an impressive milestone and testimony to Suntech’s technological prowess, robust supply chain, and support from the government. However, a mere eight years later, this erstwhile high-performer found itself undergoing bankruptcy restructuring [9].

Upon a retrospective examination, the demise of Suntech can be attributed to two pivotal factors. First, inadequate management practices resulted in poor investment decisions. Second, the company’s liquidity risks were exacerbated by an expansion of overcapacity funded by the government. The downfall of Suntech underscores the potential pitfalls of relying too much on governmental financial guidance and support, which may not only fail to foster sustainable development but can also inadvertently encourage a disregard for thorough examinations, leading to flawed decision-making.

Another example is Jiangxi LDK Solar. In 2007, LDK Solar had the largest IPO on the NYSE among all Chinese companies at the time. However, in its ambition to become the global leader in photovoltaic technology [10], LDK suffered a precipitous decline after the financial crisis. With a staggering debt-to-equity ratio of 102.7%, well beyond the 40% maximum allowed typically for Chinese photovoltaic companies as per prevailing policies, LDK began to run into problems. Its predicament continued despite the injection of RMB 3 billion in bailout funds from the Municipal Government of Xinyu City in Jiangxi province as well as the commitment of additional local state-owned capital.

An even more dramatic case unfolded in Wuhan’s investment in Hongxin Semiconductor in 2017. Despite receiving considerable funding amounting to RMB 128 billion and seemingly making strategic moves such as hiring experienced executives and acquiring a lithographic machine from ASML, a leading Dutch supplier for the semiconductor industry, Hongxin mortgaged the idle lithographic machine just two years later. Per a Tencent report [11], an investigation found executives had partnered with Wuhan officials to establish a shell company called Beijing Light Blueprint, which then created Hongxin. Hongxin had borrowed money from local banks in the name of Torch Construction Group, their primary contractor, and had been granting new loans to pay off previous debts. Through Torch Construction Group, they offloaded debts and risks onto banks, subcontractors, and suppliers while accruing substantial profits under the camouflage of being a semiconductor enterprise benefiting from government support. As this fraud was exposed, the Wuhan government took over the company and sought opportunities to sell it off.

These cases offer valuable lessons, underscoring the need for diligent oversight of the government’s industrial guidance funds and the implementation of robust accountability mechanisms to prevent the misuse of funds or overzealous strategies and mismanagement. However, the nature of “experimentation, learning and adaptation” implies that imperfections and failures will occasionally happen, but it also means that the mechanism allows for self-correction and has so far been proven quite effective.

LEARNING FROM THE PAST AND LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

Leveraging its large-scale organizational capabilities, China continues to refine its development model through experimentation, learning and adaptation while, at the same time, embracing key concepts such as “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,” “building a community with a shared future for mankind”, and “Chinese modernization”. This development model and its concepts will continue to drive China forward, enabling it to play an increasingly more critical role globally.

These concepts were developed in the context of China’s history, culture, and civilization.

Cultural and Civilizational Origins of the Development Model

China has a long and illustrious history, culture, and civilization. It has absorbed philosophies ranging from locally-born “Hundred Schools of Thought” during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Period (around 770 – 221 BC) to the adoption of Buddhism from India since the Han Dynasty (around 206 BC–220 AD). While Confucianism and Legalism have been China’s governance for millennia, different thoughts, such as Daoism and Buddhism, have also significantly impacted Chinese thought. Moreover, other schools of thought, such as the Strategists, Militarists, Mohism, Yin-Yang, Logicians and others, have left their mark on Chinese philosophy and culture as evidenced by the common usage of many of their concepts in Chinese idioms which are still practiced today.

During the Han Dynasty, the imperial court decided to take on Confucianism as the only guiding school of thought and abandoned all others. Despite that shift, many other schools of thought still continued to linger on. As a result, Chinese culture has always been characterized by diversity and inclusivity, even while Confucianism, as the major guiding philosophy, did profoundly influence Chinese culture. In modern times, the Chinese also embraced modern science and Marxism. Of course, Marxism itself was Sinicized to some degree to fit the Chinese context better. Further, since its reform and opening up, China has also embraced core market economy principles.

This process involved repeated cycles of experimentation, learning, and adaptation, forging a development path toward “Chinese modernization” that combines tradition and modernity. President Xi Jinping underscores, “learning from the past, looking to the future,” which means that as it develops and evolves its path forward, China also looks to its past and leverages its vast reservoir of experiences, knowledge and synthesis for inspiration in the development of its future.

In the early 1990s, Chinese leaders began to talk about the concept of a “socialist market economy”, which may have appeared contradictory to many people. However, as Bob Ching, the founder of Boston Consulting Group’s China practice, noted, Chinese leaders recognized that this seemingly conflicting concept was internally coherent. Decades later, China’s extraordinary economic development

has demonstrated that this once-seemingly contradictory concept could not only work and but could work exceptionally well. In other words, Bob was right.

The notion of “veering between two apparently opposite forces” is crucial to Chinese culture. In Daoism, Buddhism, and the Yin-Yang school of thought, everything in the world is made up of two opposing factors, which may appear to be opposite to each other, but work as one.

As stated by Philip P. Pan in his article, “The Land that Failed to Fail” in The New York Times in 2018, “China has veered between these competing impulses ever since, between opening up and clamping down, between experimenting with change and resisting it, always pulling back before going too far in either direction for fear of running aground.” [12] Although Pan did not say why China was able to do this, he was perhaps the first person from the West to explain why China has shown such resilience in its development. Personally, I agree with Pan’s perspective that China has been “veering between two competing sides” and then will typically “pull back before going too far in either direction.”

Exhibit 6: The Cover of The New York Times article, The Land that Failed to Fail, by Philip P. Pan

Source: The New York Times

In fact, the concept that “two opposing forces can co-exist” is not limited to China but is also prevalent in other civilizations. In business, I have found striking analogies in the realm of corporate strategy, organization, and leadership.

Contrary to hitherto static theories on business strategies, the 1998 book “Competing on the Edge”, co-authored by Kathleen Eisenhardt, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, and Shona Brown, her Ph.D. student at that time, point out that the context of business strategy is the environment in which the company operates. That context, by nature, evolves, requiring businesses to continuously adapt and adjust their strategy to stay relevant.

Exhibit 7: Core Ideasof Competing on the Edge

Source: Harvard Business School Press, Internet, Gao Feng analysis

As the book’s subtitle, “Strategy as Structured Chaos” suggests, the competitive landscape and business environment in which a company operates will inevitably veer between “structure” and “chaos”. It is neither entirely ordered nor entirely chaotic (disorderly), and the boundary between the two can constantly shift over time and space. In a highly complex and rapidly changing business environment, a corporate strategist should understand the implications of the two seemingly opposing forces and then make judgments about what necessary actions need to be taken — in a timely manner — to adjust and balance. Eisenhardt and Brown suggested that finding a suitable balance between control and autonomy, centralization and decentralization, as well as stability and change, is crucial. Any management approach that only considers one side of the picture is often vulnerable amid rapid changes in the business world. According to Eisenhardt and Brown, formulating an effective corporate strategy in an ever-changing environment requires striking a balance between control and chaos — on a continued and dynamic basis.

Jon R. Katzenbach, my former colleague at Booz & Company, is an expert specializing in organizations. According to him, there is often a coexistence of “formal organizations” and “informal organizations” within an organization, and it is crucial to maintain a balance between the two. They coexist in a company’s operating model. A formal organization is the management structure that develops as a company grows, and it is the combination of rational elements such as rules, hierarchy, and performance metrics. In this kind of organization, most executives are trained with “hard courses” in finance, technology, and operation, and they are equipped with the skills to use tangible tools like organizational charts, process charts, and balanced scorecards to support their work.

On the other hand, the informal organization comprises emotional elements that hide beyond the boundaries of the formal, including values, emotions, behaviors, anecdotes, cultural norms, and peer relationships. This collection of “soft power” can have a subtle yet profound impact on every business. Even the most rational manager must admit that the informal organization, particularly during the journey of transformation, can lead to significant impacts, such as the rise of unforeseen grassroots leaders and the quick self-revamping and iteration of business units. However, the informal organization can also have adverse impacts, such as hidden dissenters, anxiety, and fear that can hinder progress.

The formal organization represents the organization’s consciousness, while the informal organization represents its subconsciousness. A skilled leader would know how to maintain and improve the formal organization while actively mobilizing the informal organization so that both can be developed in tandem. For any organization, the capability to lead outside the lines by balancing “soft power” and “hard power” to achieve top-notch performance is often the most critical leadership skill.

The concept of embracing opposing forces within an organization resonated with Huawei’s Ren Zhengfei. A feature from the May 2015 issue of Sino-Foreign Management reported that when Huawei topped the big league of global telecom equipment players in 2014, this is when its transformation journey also commenced. Corporate success resembles balancing on a tightrope, emerging not from established patterns but by navigating change and chaos through experience and periodic setbacks. As Ren stated, the optimal path materializes through a compromise between “shades of gray” – reconciling and tolerating complex, contradictory poles. This temporary harmony enables progress.

Such “shades of gray” solutions capture the essence of “competing the thought on the edge” – integrating yin-yang style opposing forces. It suggests that growth arises from the interaction between countervailing tensions. Huawei’s ascent showcases how synthesizing multiplicity and encouraging diversity propels organizations forward. At the edge of chaos lies order; at the edge of discord lies equilibrium. By mastering the art of paradox, visionary leaders transform struggle into strength.

In his 2019 book, “The Opposable Mind” [13], Roger L. Martin, former Dean of the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, states that an excellent leader must have “the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function,” and “instead of choosing one at the expense of the other, generate a creative resolution of the tension in the form of a new idea that contains elements of the opposing ideas but is superior to each.”

Martin argues in his book for the significance of imaginative leaders with minds that embrace opposition. Leaders must recognize that although the existing model may have enough information, it still needs improvement. Leaders with flexible minds frequently seek multiple hypotheses when making decisions and tolerate and encourage opposing ideas. When faced with opposing ideas, they do not simply choose one over the other but, instead, they develop an innovative new solution that integrates and goes beyond the existing ideas. This is also one of the development models that China’s leaders have been practicing.

Let us bring our attention from the West back to China.

China’s large-scale organizational capabilities have their origins in the Confucian tradition. The Chinese literati class would follow a philosophy of “Self-cultivation, family management, state governance, and bringing peace to all under heaven (修身,齐家,治国,平天下).”The idea of serving the world and the people was gradually extended from the individual to the wider community, demonstrating that Chinese literati not only considered themselves and their families but also the country and the world as a whole. This way of thinking embraced both the individual and the collective. The Chinese call this the “Literati Spirit (士大夫精神).”

Indeed, many historians have criticized Confucianism. According to them, Confucianism hindered the development of modern science and technology in China, leading to China falling behind Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. Kenneth Pomeranz also discusses this phenomenon in his book, “The Great Divergence”. Nevertheless, Chinese intellectuals persisted in their efforts to revitalize China with their distinctive “Literati Spirit”. Their primary reference points were key aspects of Western thought and history, specifically the Renaissance, the Enlightenment Period, and the First Industrial Revolution.

Today, we can still observe that the Literati Spirit still exists in many Chinese people, but it has taken on a new form. This spirit is manifested not only in government officials but also in entrepreneurs. The book “Class of 1992: The Business Principles and Aspirations of the ‘New Literati’ Entrepreneurs,” by Mr. Chen Hai in 2012, revisits the emergence and development of the “Class of 1992” of entrepreneurs, documenting their lives before and after 1992.

Exhibit 8: Cover of The Class of 1992: The Business Principles and Aspirations of the “New Literati” Entrepreneurs

Source: CITIC Press Group

The year 1992 marked a milestone in China’s economic reform. Following Deng Xiaoping’s visit to the South and the 14th Party Congress, the notion of a “socialist market economy” was introduced. After several decades of development, China has created an economic miracle that still surprises the world. This period also gave rise to a group of ambitious and self-driven entrepreneurs, many of whom are commonly known as the “Class of 1992.”

China’s traditional education has upheld the notion of “elites governing the country” and “those who excel in education should serve in government”. However, since 1992, a growing number of elite government officials, intellectuals, and other members have gradually departed from the system, hoping to explore new opportunities in the market.

They are the “New Literati” referred to in the book, who were previously part of the public sector but have now emerged as successful figures in the business world. Prior to reform and opening up in the PRC – and the new opportunities that reform and opening up brought to the Chinese elite – the elite basically had only one (primary) career choice, which was a career in the public sector. With the reform and opening up, the best Chinese had another choice: to become entrepreneurs. Many Chinese would see this phenomenon and would migrate from a “single track” system to a “dual track” system.

As noted by Mr. Chen Hai, when one examines the resilience and vitality of an economy, one needs to find out how entrepreneurs are split.

China’s large-scale organizational capabilities have been a crucial part of the country’s DNA since the formation of the PRC. This allows effective nationwide mobilization of resources, now augmented by modern management approaches and technology.

Traditional Chinese philosophy has also influenced President Xi Jinping, his vision of “Build a Community with a Shared Future for Mankind” draws its origins from ancient China, dating back over 2,000 years ago during the Zhou Dynasty (1046 BCE – 256 BCE) when the Chinese referred to their ideal world as “tianxia” (天下) or “all under heaven”. Professor Zhao Dingyang at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences conducted extensive research on this concept. Tianxia implies a world system that makes the world a political entity, a coexistent order with the world as an integrated political unit. To understand tianxia is to take the whole world as the unit of thinking to analyze issues, thereby transcending the modern mindset of nation-states. Tianxia is a world system founded on the ontology of coexistence.

To fully understand tianxia, we must examine issues from a global perspective and transcend the limitations of a modern nation-state mindset. Though an ideal, it remains a pillar of Chinese civilization.

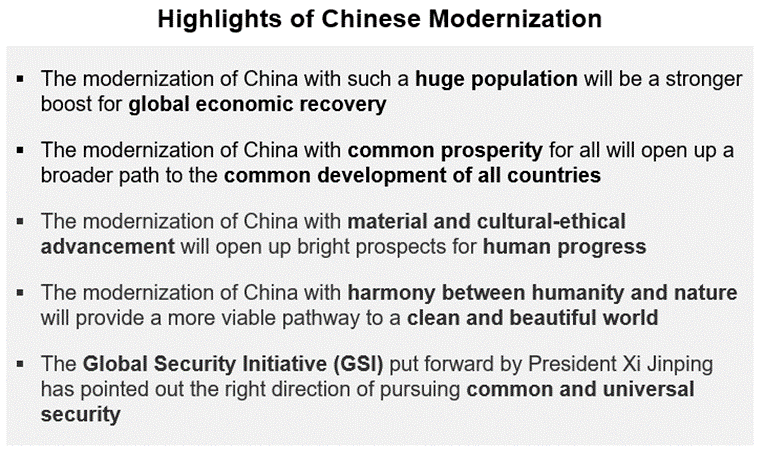

At the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2022, President Xi Jinping announced that Chinese modernization would be a crucial development concept to promote the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. This concept encompasses the modernization of “a huge population, common prosperity for all, material and cultural-ethical advancement, harmony between humanity and nature, as well as peaceful development.” Notably, many of the core concepts are propositions derived from Chinese history, culture, and civilization, both traditional and modern.

The notion of “adhering to harmony between humanity and nature” emphasizes a sense of responsibility to form an interconnected community of life for humankind and nature. Humanity must respect, adapt to, and protect the natural world. As a traditional agricultural society, the Chinese have long understood and appreciated the importance of coexisting harmoniously with nature. This profound philosophy of “unity between humanity and nature” was summarized by Wang Yangming in the Ming Dynasty (early 15th century), encapsulating the Chinese perspective on peaceful coexistence with nature. This concept is similar to the notion of “sustainability” in the Western world today.

Exhibit 9: Highlights of Chinese Modernization

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China, Gao Feng analysis

Despite China’s rich history, culture, and civilization, it is not reasonable to expect that the Chinese people have the solutions to all global challenges. Chinese society has gradually improved as it has experienced a diverse range of events, encompassing both successes and failures, unity and separation, and positive and negative developments.

In times of separation and division, when different powers competed for control, strategic thinking was crucial and required a comprehensive approach. Additionally, promoting an efficient governing structure across a vast territory during times of unity requires strong organizational capabilities and a well-designed governance system. Under such a situation, a mechanism for enabling capable individuals to serve society would be essential.

With its long history and vast territory, China has witnessed frequent military conflicts and power struggles that often led to power transfers between rulers. However, Chinese culture and civilization have always been intact; along the way, they have absorbed many new ideas. Its inclusiveness and diversity have become the key to its effectiveness.

Dynamism Continues

Like any system, China’s development model is subject to economic cycles. Since China’s reform began 40 years ago, its economy has sometimes experienced volatility due to external and internal factors. For instance, inflation hit 24.1% in the 1990s [14], and the 2008 global financial crisis triggered a RMB 4 trillion stimulus package. More recently, COVID-19 led to declines in consumer spending, real estate debt issues, and high unemployment.

Yet despite fluctuations, China has shown remarkable resilience – what New York Times’ Philip P. Pan described as a “Land That Failed to Fail”. Having worked in China for 30 years, I had first-hand experience with this vitality. BCG’s founding partner in China, Bob Ching, noted long ago that China’s “socialist market economy” was not a contradiction but a viable model. Although initially I did not quite understand what he meant, his point drove me to keep observing China’s progress. Over time, and with years of deep business experience, I began to understand what he meant.

No system is perfect, but the ability to self-correct against a set of principles, and a sound underlying structure, has helped China create a development model that can address myriad issues efficiently. This model has helped to generate fast growth, reducing economic and social volatility, and has created an overall and durable resilience.

Despite its overuse, the term “dynamism” more or less captures the essence of the Chinese way. The Chinese way is certainly not perfect but it has successfully driven China’s experiments, economic growth, and development over the last four decades. It is a unique capability that has arisen from the Chinese people’s collective will and strategic goals generated throughout history and complemented by China’s agile mechanisms in the global environment. And it’s worth noting that China did not start with a detailed blueprint. Still, China’s long and extensive history, culture and civilization have created a capacity for multiple streams of thought and a willingness to learn, adapt, and synthesize. The Chinese recognition that the world’s phenomena often consist of two apparently opposite forces, and being able to manage the interacting relationship properly, is often the key to finding a solution. This is what underlies China’s resilience and has been one of the keys to its success.

Epilogue

While writing this article, I was of course closely following the news about China’s current economic challenges including the property market issues and unemployment in the youth sector. Like any large economy, it’s quite natural that China should face such a wide range of problems. In fact, these issues should be expected given China’s size and complexity, and the very complicated and fluid geopolitical and economic situation that China now finds itself in.

There is no doubt that China will need to – and is well-prepared to – address these challenges. Some of them will be resolved rather easily with minor policy adjustments, while others may require deep and extensive changes and reforms. Needless to say, they will take some time.

What I describe in this article are the fundamental reasons how and why China works. Why has China proven time and time again to be so resilient? How has China overcome challenge upon challenge and remained strong, optimistic and open for business? Drawing upon my decades of experience in international business, I answer these complex questions.

Needless to say, there is doubt that China’s current economic challenges will provide yet another opportunity for China to demonstrate its great resilience. And, of course, new and unexpected challenges (and opportunities) will invariably pop up along the way. That’s just life.

My hope in writing this article is that I might provide insights and guidance to leaders of global businesses as they develop their corporate strategies with China playing an essential role. I believe that sharing my knowledge and experience regarding the underlying logic of how and why China works can, in some small way, contribute to the success of all businesses. This is good for China and good for the world.

References

- 10287.45 kilometers, Urban Rail Transportation Statistics and Analysis Report 2022, Sohu News (2023.04.01).https://www.sohu.com/a/661817139_121123909

- Recognition ceremony held for national poverty alleviation, Gov.cn (2021.02.05).https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-02/25/content_5588866.htm#1

- The China story behind Apple’s $3 trillion valuation with Doug Guthrie, The China Project. https://thechinaproject.com/2022/01/07/the-china-story-behind-apples-3-trillion-valuation-with-doug-guthrie/

- This industry has reached a value of hundreds of billions. What has Hefei done correctly? STCN (2023.02.21).http://www.stcn.com/article/detail/798940.html

- How does Lenovo’s premium laptop assembly factory help Hefei’s economy take off, 163.com (2022.07.27).https://m.163.com/dy/article/HD93LDDN0553AZLI.html

- The finalized RMB 7 billion strategic investment agreement: why NIO relocates its HQ to Hefei, 21st Century Business Herald (2020.04.30).http://www.chinatopbrands.net/s/1450-5731-17124.html

- VW Anhui aims to keep on investing in Hefei with a total planned investment of RMB 23.1 billion, EVinChina (2023.06.01).http://www.evinchina.com/newsshow-3405.html

- VCGF: evolution and case study, Zhihu (2023.04.25).https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/624703525

- Lessons Learned on Government-Market Relationship, CNCnews (2016.08.02).http://theory.people.com.cn/n1/2016/0802/c401815-28604378.html

- The former PV giant’s chairman during the bankruptcy and restructuring period is behind bars, The Paper (2018.07.10). https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_2251702

- The dramatic story of Hongxin Semiconductor: a scam against government and banks by shareholders from a shell company, Tencent

- The Land That Failed to Fail by Philip P. Pan, The New York Times (nytimes.com) (2018.11.18). https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/11/18/world/asia/china-rules.html

- The Opposable Mind: How Successful Leaders Win Through Integrative Thinking by Roger L. Martin, Harvard Business Review Press (2009.7.13)

- Historical inflation and outlook, Yingda Securities (2021.05.11).https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202105121491224021_1.pdf?1620815825000.pdf

What Drives Business and Innovation in China?

What Drives Business and Innovation in China?