What is your Right-to-Win? 你凭什么赢?这是所有企业在考虑战略问题时必须回答的问题。你凭什么赢是靠你的与众不同和能足够防御竞争的一套能力(a set of differentiated and defensible capabilities). 这些能力可以自生亦可从生态伙伴中提取,但必须符合上述两个条件。许多企业或其咨询顾问缺乏严谨考量,没法将 Right-to-Win 正确地定义,以致战略无效。

What is your Right-to-Win? 你凭什么赢?这是所有企业在考虑战略问题时必须回答的问题。你凭什么赢是靠你的与众不同和能足够防御竞争的一套能力(a set of differentiated and defensible capabilities). 这些能力可以自生亦可从生态伙伴中提取,但必须符合上述两个条件。许多企业或其咨询顾问缺乏严谨考量,没法将 Right-to-Win 正确地定义,以致战略无效。

,

企业战略里的一个核心问的问题是:”你凭什么赢?” (What is your Right-to-Win?” 即是你有什么独特的能力是比你的竞争对手更强的?㫫然,这是核心竞争力理论的延伸。在西方,特别在美国,企业领导者往往会从过去式来判断他们的能力在那里。在今天快速变化的时代裡,这当然是不足够的。关键不是你目前能力如何,而是你能在有限时空内通过什么方法来建立你的独特竞争优势。熟悉吗?这就是”战略第三条路” 的核心理念。What is your Right-to-Win?

Edward Tse

Debunking Myths on Chinese SOEs

Original published by Nikkei Asian Review titled “Chinese SOEs are Focused on Business, Not Politics” on September 13, 2019. All rights reserved.

In the eyes of some politicians and media in the West, Chinese state-owned enterprises are little more than corporate vehicles for carrying out Beijing’s policy agenda. This perspective has led to calls to restrict SOEs’ investments and acquisition of other companies and technologies.

This is a shortsighted view. Although I am from Hong Kong, not mainland China, and am not a member of the Communist Party, I have served at different times as an independent board director at four Chinese SOEs since 2006: Shanghai Pharmaceuticals Holding, Baoshan Iron & Steel (Baosteel), the holding company of carmaker SAIC Motor, and currently, China Travel Service (Holdings) Hong Kong.

In inviting someone like me to join their board, these companies sought an external perspective to help ensure proper governance. At no point before or during any board meeting was I ever asked to vote a certain way. No one tried to interfere with my professional judgment on what would be good for the companies.

In all these years of board meetings, I cannot recall any discussion that centered on serving a certain political agenda. Rather, the discussions were inevitably about business. Just as with a large Western company, the talk was of revenue, profit, market share, cash flow and returns on investment and how to improve them.

Of course, government policy would at times be a matter for discussion. Beijing has for some years been pushing through a consolidation of the steel sector, for example, so that inevitably surfaced in deliberations when I was a director at Baosteel.

It is also important to note that Chinese SOEs are far from uniform in their governance or outlook. For companies involved in sectors that touch on national security, discussions about the government’s agenda would be much more natural than in consumer-focused sectors like travel and autos.

Other SOEs are tasked with providing public services, such as infrastructure, health care and education. Notably, their evaluation of projects is generally based more around addressing utility for the public than a simple internal rate of return.

In open sectors like retail, consumer goods or pharmaceuticals, however, Chinese SOEs have to survive in perhaps the world’s most intensely competitive market.

Many of these SOEs feel they are falling behind their private-sector peers in innovation and are under pressure to catch up or collaborate with them. They are particularly concerned with whether they can continue to effectively compete as China opens up more sectors to private-sector participation, especially by foreign companies.

Even in sectors like banking and insurance where SOEs traditionally held unshakable positions, they are no longer immune to competition from the private sector. Consider how Alibaba Group Holding affiliate Alipay and Tencent Holdings’ WeChat Pay now dominate online payments. With a focus on adapting technology, Ping An Insurance Group has overtaken state-owned peers like China Life Insurance to become the country’s largest insurer.

Chinese SOEs do enjoy some advantages because they are owned by the state, but this is most true in sectors involving national security or public infrastructure, like energy and telecommunications. In such cases, the SOEs’ ownership of key assets and their protected operating franchises are somewhat comparable to those of public monopolies like water companies or postal services in Western countries.

A number of them, such as telecommunications infrastructure company China Tower, also benefit from having other SOEs as their main clients.

Local governments in China also tend to favor purchasing from SOEs based in their region as a means of supporting them as significant area employers and taxpayers. This can come into play, for example, with orders for official vehicle fleets.

Further, state companies have long had a significant advantage in getting access to bank credit from the SOE-dominated banking system but this has been changing.

According to Moody’s Investors Service, SOEs accounted for 52.6% of outstanding bank corporate lending as of Dec. 31 even though they have been generating less than 40% of overall output.

But after President Xi Jinping declared private enterprise to be an essential part of China’s economic system late last year, the country’s financial regulators pledged to widen access to credit and financial support for the nonstate sector.

These changes are taking time to implement, but policy is headed in the right direction and technology is helping to take the place of ownership in assessments of the creditworthiness of individuals and small businesses.

Chinese SOEs also carry social burdens much more often than private companies. As an SOE, Baosteel had to invest considerable time and effort to address the labor and community impact when it shut down older factories in urban areas to move to cheaper locations.

Until now, China’s parallel structure of SOEs and privately owned companies has largely worked well. As a whole, this duality has been a source of resilience for China, not a drag.

Yet officials in Beijing have identified reform of state-owned enterprises as an imperative. Of late, this effort has focused on diversifying the shareholding of many SOEs. This has included the introduction of private capital in some cases.

To make mixed ownership reform a success will require the establishment of proper corporate governance structures and principles. The role of the state agency that oversees SOEs will have to shift over time from direct control to being one among a number of shareholders. These changes will help SOEs to be able to compete effectively in China’s fast-changing and increasingly innovation-driven environment.

About the author:Dr. Edward Tse

CEO of Gao Feng Advisory

Dr. Edward Tse is founder and CEO of Gao Feng Advisory Company, and a founding Governor of Hong Kong Institution for International Finance. One of the pioneers in China’s management consulting industry, he built and ran the Greater China operations of two leading international management consulting firms for a period of 20 years. He has consulted to hundreds of companies, investors, start-ups, and public-sector organizations (both headquartered in and outside of China) on all critical aspects of business in China and China for the world. He also consulted to the Chinese government on strategies, state-owned enterprise reform and Chinese companies going overseas, as well as to the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. He is the author of several hundred articles and four books including both award-winning The China Strategy (2010) and China’s Disruptors (2015) (Chinese version of 《创业家精神》).

The Resilient Organization. This organization is flexible enough to adapt quickly to external market shifts, yet it remains steadfastly focused on and aligned with a coherent business strategy. This forward-looking organization anticipates changes routinely and addresses them proactively. It attracts motivated team players and offers them not only a stimulating work environment, but also the resources and authority necessary to solve tough problems.

Edward Tse

Gao Feng Advisory’s CEO Dr. Edward Tse’s article was published in his regular column on Brazil’s HSM Management Magazine. In this article, Dr. Tse wrote about China’s mega platforms companies. China’s innovations are not just about monetization. It’s an inspiration for new intellectual capital on how businesses generate their strategy and innovations. They enrich the world’s thought leadership.

English Version

China’s Mega Platforms Organizations

The most valuable Chinese companies today are typically “mega ecosystem” players which operate networks of businesses that can support each other and supplement each other’s capabilities. Internet giants, Alibaba and Tencent, arguably the most well-known companies in China, are now in the top ten of public companies by market capitalization.

The notion of a business ecosystem is not new. Apple, one the world’s most valuable companies, was a pioneer in this regard. Other leading U.S. tech companies such as Amazon and Alphabet are also ecosystem players. Chinese companies, however, have turned out to be even more adept at building such organizations.

Prime examples of mega ecosystems in China today include Alibaba, Tencent, and Xiaomi. Building out from their original core businesses, they have jumped into a string of new sectors.

Alibaba started as a small business-to-business online marketplace almost 20 years ago and jumped in with consumer-to-consumer site Taobao and later business-to-consumer site Tmall. To support these businesses, Alibaba started Alipay to support mobile online payments and then used it as a platform to offer wealth management services.

Today, Alibaba’s has also branched into areas including “automobility”, “big health”, media, “new retail”, location services, cloud services, and smart logistics.

Xiaomi, the youngest Fortune 500 company, is a leading ecosystem players with a range of businesses in hardware, internet services and new retail. By partnering up with a hundred more start-ups since 2013, Xiaomi has been able to add many more products onto its In-ternet of Things (IoT) platform, without having to produce them in-house. Today, Xiaomi offers more than 300 lifestyle products and are connecting more than 170 million devices (excluding mobile phones and laptops).

Xiaomi’s smartphone business is becoming a smaller part of its business, while internet services are growing. To this end, it has added to its portfolio apps ranging from online games, eBooks, live streaming, music and videos, internet finance, cloud services and automotive social platforms. This allows them to monetize on ser-vices after selling low-priced hardware, which could drive a large part of revenue going forward.

With such a large range of products in its portfolio, Xiaomi has made the jump into new retail that aims at seamlessly interconnecting its online and offline channel. Over the years, Xiaomi has built interac-tions and close relationships with its supporters, affectionately called the “Mi-fans.”

Xiaomi’s founder and leader, Lei Jun, has said that the next strate-gic move would be building a smartphone + AIoT (AI and IoT) in anticipation of 5G technology. With this strategy, it is likely that Xiaomi would extend its ecosystem, and increase in the variety of Xiaomi applications.

When Chinese companies sense a market opening, they would quickly make the jump to capture the opportunities and try to make up the gaps in capabilities through ecosystems of collaborative part-nerships. In contrast, most foreign corporations tend to focus on what they have been doing all along and avoid “diversification”. Foreign companies operating in China have now increasingly recog-nized this difference and are catching up by learning from Chinese companies and participating into their ecosystems.

About the Author

Dr. Edward Tse is founder and CEO of Gao Feng Advisory Company, and a founding Governor of Hong Kong Institution for International Finance. One of the pioneers in China’s management consulting industry, he built and ran the Greater China operations of two leading international management consulting firms for a period of 20 years. He has consulted to hundreds of companies, investors, start-ups, and public-sector organizations (both headquartered in and outside of China) on all critical aspects of business in China and China for the world. He also consulted to the Chinese government on strategies, state-owned enterprise reform and Chinese companies going overseas, as well as to the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. He is the author of several hundred articles and four books including both award-winning The China Strategy (2010) and China’s Disruptors (2015) (Chinese version «创业家精神»).

As a consultant, you know you made it when clients begin to use your frameworks and nomenclature to talk about their own business. Thought leadership is key to problem solving and in turn is key to creating lasting client impact.

As a consultant, you know you made it when clients begin to use your frameworks and nomenclature to talk about their own business. Thought leadership is key to problem solving and in turn is key to creating lasting client impact.

本文是高风咨询CEO谢祖墀博士的最新观点文章,他重温和回顾了《边缘上竞争》(Competing on the Edge)的理念。在此理念的指导下,于五年前提出了“战略的第三条路”的概念。

最近华章出版社与我联络,他们说他们计划在2001年出版的《边缘竞争》(华章出版社用了《边缘竞争》为中译名字,我觉得《边缘上竞争》与英文原文较吻合)一书,在近期重新发行,并希望征求我的意见。

这比较突然而来的邀请,让我再度想起来这本书在企业战略管理历史上的重要性,很可惜,这本书在国内几乎没有什么人听过,对这书里提出来的理念几乎完全不知道。所以在这次的专栏中,我想写一篇对这本书的重温和回顾。

我接触这本书应该已经有20年左右,看的是它的原文英文版本。它给我留下来非常深刻的印象。因为我的工作关系,一直以来我非常关注有关企业战略的书籍。这本书应该是第一本从真正意义上介绍动态战略的一本书。于90年代末出版,对今天还未过时,是一本真正掌握到动态战略真谛的书籍,说它是超时代并不过分。

《边缘上竞争》(Competing on the Edge)一书于1998年出版,由美国斯坦福大学两位女性学者肖纳·布朗(Shona L. Brown) 和凯思琳M. 艾森哈特(Kathleen M. Eisenhardt) 合著,主要作者是布朗女士。该书针对当时的计算机行业的发展给企业和管理界带来的新的问题。在书中她们提出的一个在当时来说全新的战略管理理论。该理论吸收了环境复杂性理论(Complexity Theory)和进化理论(Evolutionary Theory)等前沿思想,并对分布于全球的12家企业进行了实地调查和深入研究。

在这本书出现之前,几乎所有的企业战略理论都是以静态为主的,其中有代表性的包括波特五力模型,BCG矩阵,以及蓝海战略等。主导思想是:企业致胜之道是要为自己寻找到一个最优胜的定位。

在1990年代初期于学术界和管理咨询界出现的重要的新的战略理论。于1990年美国密歇根大学商学院两位教授C•K•普拉哈拉德(C.K. Prahalad)和加里•哈默(Gary Hamel)提出了核心竞争力理论。该理论指出一家企业要成功必须按照自己的优势来做,亦即所谓核心竞争力。而1992年时,我当时在BCG时的三位合伙人斯托克(George Stalk, Jr.),埃文斯(Philip Evans)和舒尔曼(Lawrence E. Shulman)发表了《基于能力的竞争》(Competing on Capabilities)。他们认为,企业的持续成功来自企业已建立的内部能力,而战略的精华在于它能否以动应变,从而确立并形成一种他人难以效仿的组织能力。按自己的强处和能力来做事所讲当然是一般的常识,这套理论后来亦是成为了在过去二十多年支配着西方商界和投资界的主流战略思想理论。

以后,不少咨询公司仍然用这些理论来标榜自己。如贝恩(Bain)咨询公司的祖克(Chris Zook)和艾伦(James Allen)在2001年出版《从核心盈利:动荡时代的增长战略》(Profit from the Core: Growth Strategy in an Era of Turbulence) ,书中提出了基于核心竞争力的增长战略。这一理论和密歇根大学的核心竞争力理论和BCG能力竞争理论有着相同的原理。

以至2008年,亦即原来核心竞争力理论出版18年后,博斯咨询公司(Booz & Company)才提出“以能力驱动战略”(Capabilities-Driven Strategy)的概念。其核心思想是:企业必须依赖3至6个最强的能力和它们形成的能力体系来进行竞争。从本质上,与原始的核心竞争力方面理论没有很大的突破。

在此期中,有些学者和咨询顾问们曾经尝试将动态的思想注入能力战略理念之内。较著名的是加州大学伯克利分校的教授大卫·J.蒂斯(David J. Teece)于1997年他提出了动态能力(Dynamic Capabilities)的概念。基本上他将能力从原来的静态状态延伸到动态的状态。举例来说,他说速度、感应和应变能力对企业是非常重要的。但蒂斯的理念没有超越原来的核心竞争力/能力的思想范畴,本质上没有突破。

《边缘上竞争》是第一本将动态战略从本质上整体介绍出来的一本书。“动态”不只是将静态能力重新包装一下而已,而是在思想和理念方面整体上的一种提升,亦是一种系统思维。它书名的副题是《有序中混沌的战略》(Strategies in Structured Chaos),它说明了我们处于的竞争和经营环境将是在有序(Structure)和混沌(Chaos)之间的徘徊,没有任何时候,我们所处于的环境将是完全的有序但亦没有任何时候是完全的混沌。战略最基本的真谛就是在有序和混沌之间不断的动态平衡。肖纳•布朗(Shona L. Brown)在书内提出了几点非常重要的观点。她说未来企业经营环境的主要特征是高速变化和不可预测性,因此,战略管理最重要的是对变革进行管理,这主要表现在三个方面:一是对变革做出预测;二是对变革做出反应;三是领导变革,即走在变革的前面,甚至是改变或创造竞争的游戏规则。

在当时1990年代末期,这些观点是划时代的,布朗应是第一个将这些理念做系统性介绍,同时她亦提出了动态战略的十项原则:

1. 优势是短暂的;2. 战略是多样化的,迭变的和复杂的;3. 不断地自我发现是目标;4. 组织简单化,作用极大化;5. 从过往而来;6. 向未来延伸;7. 保持适当的节奏和步伐;8. 将战略拓展出来;9. 从业务层面启动战略;10. 将业务与市场紧密挂钩和不断整合到企业整体。

从战略角度来说,我认为最主要的原则是第一条、第二条、第三条、和第七条。第一条:“优势是短暂的”,说明企业的所有优势都是短暂的,没有什么是“持续”的。企业应该不断地发掘和发展新的优势来源,将改变视为机遇而不是威胁。第二条:“战略是多样化的,迭变的和复杂的”,说明了战略不是死板和静态的,它必须是动态调整的。第三条:“不断地自我发现是目标”,亦是动态思想的核心,企业没有停下来的时间,必须不断发掘新的目标。第七条:“保持适当的节奏和步伐”应是我第一次在有关战略思想的文献上看到的,不只是速度重要,保持适当的节奏和步伐一样关键。

在这本书写完以后的20年来,企业所处的经营环境经历了加速的改变,不确定性越来越高,静态的战略思想已经完全不行,作为第一个提出整体动态战略的布朗女士,她的预见的确令人佩服。当然,随着时代的变化,布朗的理论亦需进行微调。不过,她当时的视野和感觉在今天而言还是非常到位的。

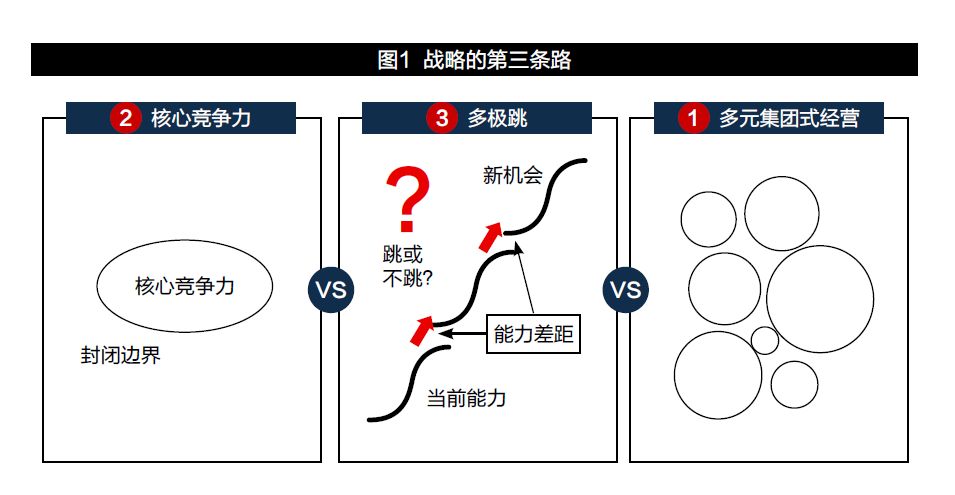

在《边缘上竞争》的理念指导下,我从五年前开始就提出了“战略的第三条路”的概念。此概念是说企业在快速发展的市场环境里,可以考虑多级跳作为动态发展的手段,而不一定需要以传统的核心竞争力/能力作为自我限制发展的枷锁。多级跳理论的基础是边缘上竞争,亦即动态战略。在未来科技发展的超快速,国际上地缘政治关系和日趋复杂的大前提下,动态战略的重要性将更加重要。在这个时候,重温布朗女士划时代的巨著《边缘上竞争》恰是最好的时机。

(注:本文图片均来自网络)

作者简介

谢祖墀 (Dr. Edward Tse) 是高风咨询公司的创始人兼CEO。同时他也是香港国际金融学会创会理事。谢博士是中国管理咨询行业最早的从业者之一,在过去20年中,他曾带领两大国际管理咨询公司在大中华区的业务。他为包括国内外的数百家企业提供过咨询服务,涉及在华商业的各个层面,以及中国在世界的角色。他曾为中国政府提供过战略、国有企业改革以及中国企业走出国门的建议。他已撰写数百篇文章以及四本书籍,其中包括屡获殊荣的《中国战略》(The China Strategy,2010年)和《创业家精神》(China’s Disruptors,2015年)。

做好咨询必须拥有将客户利益凌驾于首位的情怀。对客户有着强烈的同理心。特别是客户将他们最棘手的问题托付给你的时候,你必须尽你的能力去协助你的客户。做不到的就不是称职的顾问。

战略咨询与市场调研有着本质的差别。市调是找数据或信息,从下而上。战略咨询是解决难道,从上而下,再从下而上。往往几上几下才能找到答案。有市调背景或思维的必须将它 unlearn。 否则他/她必定不能做好战略咨询的工作。

有人说组织要像水,但水没有宏观架构,这样的组织有可能吗?应该说组织应该具有韧性调节的内在能力。它必须具有必要的柔性,同时亦需要必要的刚性。这是博斯艾伦组织 DNA 理论的核心。世上所有事物都是二元 Duality 的。

我们身处在一个充满变化的社会,经济的高速发展和价值观的急剧转变,使得企业想要在未来保持自身的稳定性和独特性变得异常艰巨。造成这种境遇有诸多因素,包括地缘政治、科技、竞争等。与过去不同,企业不应亦不能只是盲目地追求无尽的增长,而是在这种变化多端的环境里掌握适当的节奏并进退有度——能进亦能退,能攻亦能守,能聚亦能散。归根到底,企业要把握的是“如何活下去”的秘诀,其中,企业的领导者扮演着极其重要的角色。企业“活下去”且“基业长青”究竟需要怎样的领导力?

在我看来,一家成功企业的领导者首先自身需具备清晰的意识,通过个体的张力产生组织牵引力,带领整个企业朝着正确的方向前进,帮助企业在清醒的意识下去思考问题,思考“我们是谁”、 “我们需要做什么”、“我们的追求和价值观是什么”等最基本又最容易忽视的问题。

故此,优秀的领导者必须具有极强的警觉能力。在不确定的环境里,企业在做决定时,警觉型的领导者的作用是协助企业提高做出正确决定的概率,他亦能不断地提醒整个组织,在清醒的意识下去思考潜在的风险与挑战,并为之做出准备,建立起强大的防御机制和自愈能力。

在这个瞬息万变的时代,任何企业的优势都是短暂且不断变化的。一些曾经被誉为是全球最优秀的企业,如柯达、诺基亚、摩托罗拉和朗讯等,都在大浪淘沙中消失或面目全非。显然,仅仅拥有优良的品格和明确的追求已经不能确保企业“活下去”并“基业长青。企业同时需要进行“修炼”,以增强自身的“韧性”。唯有如此,企业才能在受到外界的威胁,面临不可控的风险,尤其是强劲的外来冲击力时,通过对未来的预见,有效的战略部署和投资,以及一致的组织形态和执行,不断地调整而活下去。

而企业领导者的主要责任,就是带领整个企业进行修炼。企业的修炼可以通过不同的方式来达成,集体学习就是其中重要的一种。美国管理学者彼得•圣吉(PeterM. Senge)也在其著作《第五项修炼》中提出“对话交流“(dialogue)的概念,认为团队必须摒弃固有的成见进入真正无拘无束的”共同思考“(thinking together)。美国著名的对冲基金桥水公司(Bridgewater)的领导者雷•达里奥(RayDalio)是团队共同学习的实践者。他定期让基金的投资经理聚在一起,就国际形势在没有干预的氛围里进行讨论甚至激辩,来激发团队思考的潜能。

如今,我们时常要对大量的信息进行分析,超负荷的信息和开展多重任务的工作模式侵占了我们的注意力,而注意力的缺失导致人们缺乏深度思考和深度体验,无法形成洞见,也无法将信息和知识转换为能力。所以,企业内部各级成员对于Mindfulness的学习和训练也越来越重要。Mindfulness这个词源自佛教,本意为用清晰的思维去思考事情,时刻处于一种清醒的状态。在中文里,Mindfulness常被译为“正念”,我个人并非完全认同“正念”这个翻译,更准确的的含义应是“用心来做事” 。以色列著名历史学家尤瓦尔•赫拉利(Yuval Noah Harari)选择每天花两个小时冥想,让头脑保持在一个清晰的状态,有助于更深刻地思考问题。他曾提及,如果没有冥想练习,他不可能写出《人类简史》和《未来简史》这些巨作。同理,在遭遇挑战时,保持正面积极的态度,不被情绪绑架,拥有清晰的头脑去做出最佳决策则变得十分之重要。正念能提升人的专注力、组织的开放度,并让人自我觉知,从而产生良好的正面影响。由此观之,持续学习正念将提升员工们的心智容量,发展原认知力。这样,他们才能专注于当下所经历的事务与身处的环境中,更好地参与工作。

近年来,随着Mindfulness知识的普及和其影响力的扩大,不少企业开始关注如何利用正念来提升整个企业的效率,其中不乏例如谷歌、安泰医疗保险公司(AetnaInsurance)、领英(LinkedIn)等我们耳熟能详的西方企业。Mindfulness已经在愈来愈多地渗透进这些西方领先的企业的运营与管理中,并彰显其显著的效应。“活下去”且“一直活下去”以达到“基业长青”更需要智慧的领导,引导企业与员工、客户、甚至竞争对手和生态伙伴共同领悟和发展。其实对于企业来说,这并非高深莫测的概念。不仅仅是西方企业,中国企业对此也有所领悟。华为公司就明确地指出,企业应当时刻保持“自我批判”的精神,用以强化和稳固核心价值观。在这过程中,领导者的作用尤为关键。同时,员工作为企业的个体,亦应当不断地去思考“我们做得够不够好”、“我们如何规避风险”等最关键的问题,也唯有这样才能避免在庞大的组织中迷失自己。这些问题虽看似简单,但如若不思考清楚,整个组织就会陷入被潜意识支配的状态,最终被潜意识拉入无尽的深渊之中。随之而来的,是组织的腐败和懈怠,最终恶变为不治之症。那么,究竟如何开始进行修炼呢?企业领导者可以从以下三点着手进行提升:

帮助整个企业认识到(build awareness)清晰的意识(consciousness)的重要性。

与企业内部保持良好的沟通,让整个企业清晰其目的和追求是什么,并帮助企业建立良好的品格。

带领企业进行“修炼”。通过不断重复地做一些事情,把企业不良的潜意识转换为清晰积极的显意识,使整个企业处于一种比较清晰的状态。在Mindfulness的状态下“用心做事情”,从而减小犯错的机会,并提升做对的事情的概率。无论在机会或危机来临之前,就做好准备。

企业“活下去”,是最低也是最高的组织目标。“活下去”且“一直活下去”以达到“基业长青”更需要智慧的领导,引导企业与员工、客户、甚至竞争对手和生态伙伴共同领悟和发展。

原文发表于《亚布力观点》(2019年8月刊)并保留所有权利(注:本文图片均来自网络)

作者简介

谢祖墀 (Dr. Edward Tse) 是高风咨询公司的创始人兼CEO。同时他也是香港国际金融学会创会理事。谢博士是中国管理咨询行业最早的从业者之一,在过去20年中,他曾带领两大国际管理咨询公司在大中华区的业务。他为包括国内外的数百家企业提供过咨询服务,涉及在华商业的各个层面,以及中国在世界的角色。他曾为中国政府提供过战略、国有企业改革以及中国企业走出国门的建议。他被称为“中国于国际上最富经验和具权威的商业战略专家”。他已撰写数百篇文章以及四本书籍,其中包括屡获殊荣的《中国战略》(The China Strategy,2010年)和《创业家精神》(China’s Disruptors,2015年)。

Share this:

Innovations and entrepreneurship have become core to China’s culture. Young people from all over are trying to become successful. Many will fail and they know but a small number will make it. A small % of a large number is a large number. And the ones who make it will become role models for others.

By Edward Tse

December 2018

This article is the introduction to the China highlights in the State of Curiosity Report 2018 published by Merck Group

Source: Google

The last 40 years of China’s reform and market liberalization have brought profound changes and tremendous progress to the country’s economy, especially to its business landscape. Along the way, China has evolved into its own development model without consciously planning for it – a “Three-layer Duality”. At the top, the central government sets the overall development priorities. At the grass-root level, the private sector entrepreneurs are now a major driving force in the Chinese economy. In the middle, various local governments, in response to the directions from the top, compete, and sometimes collaborate in regional clusters, often by teaming up with the entrepreneurs. With both a state sector and a private sector co-existing – in some cases competing and in others playing their own distinctive roles – this duality is a defining feature of the Chinese economy.

This three-layer working paradigm has stimulated the exponential rise of curiosity-driven business innovations, especially from the private sector. The rise in workplace innovation is reflected in Merck’s 2018 State of Curiosity survey, a multi-dimensional model that measured the importance of curiosity and innovation across several countries. China, above the US and Germany, found that innovation played a meaningful role in its workplace culture. With this value on innovation, the country has shed its copycat stigma and emerged as an epicenter of tech-enabled innovations. According to reports by Xinhua News Agency last year in 2017, the internet and technology sector – ranging from AI, big data, IoT, and robotics – grew twice as quickly as the overall gross domestic product over the past decade. Born with a different set of characteristics in each generation, Chinese entrepreneurs are thriving in what is now the world’s second-largest birthplace of unicorns (unlisted companies valued at or above US$ 1 billion that established within 10 years).

Source: Google

What has enabled China to move from copycat to curious innovator?

1. First and foremost, it is due to the “why not me?” mindset. Realizing the huge gap between China and the rest of the world, especially in the early days of the country’s reform and opening, Chinese entrepreneurs were compelled to show the world that they too could succeed.

2. As the economy transformed, China’s societal pain points that once were hidden became exposed. Coupled with the prevalence of technology, especially the commercial application of smart devices through the wireless internet, these new conditions provided the breeding ground for innovations.

3. While state-owned counterparts are typically slower in responding to these changes, private sector entrepreneurial companies rose to the challenge and took on the opportunities.

4. At the same time, China’s massive market allowed companies to rapidly scale up and its hyper-competition spurred companies to speed up their innovations to stay ahead in the game.

5. Finally, along the way, Chinese companies have benefited greatly from the vast capital pool and angel investors, and the investors, in turn, have benefited from exceptional returns on their investments in China.

Regardless of whether these investors came from abroad or home, Chinese entrepreneurial companies, especially tech companies, often pattern themselves after companies in the US Silicon Valley. Leaders of these organizations often work alongside the team, making it easy for them to capture market changes and make quick decisions. These leaders (usually founders and managers) are typically strong and visionary – a common trait of Chinese entrepreneurial organizations and culture. Structures of these organizations especially during their early phase tend to be flat thereby allowing efficient response to the ever-changing business environment.

While these companies have strong leaders at the top, they also have appreciable empowerment across the organization, which may sound like a paradox. However, institutional curiosity manifests itself often in a profound manner, particularly in tech companies during their entrepreneurial phases. A few key drivers are noted for these organizations in the form of Curiosity dimensions, as defined by Merck.

The first is the openness to people’s idea: The relatively open organization structure in Chinese tech companies enables more openness and better communications among team members.

The second is stress tolerance: There are more ambiguity and uncertainty in China’s rapid and disruptive evolution. Entrepreneurs must be willing to try and embrace pressure.

The third is joyous exploration: Growing income and better living conditions over the past decade have uplifted people’s expectation that the future will be better. They’re more willing to explore a life that’s better and more joyous.

Last but not least is deprivation sensitivity: Entrepreneurship makes people more sensitive to deprivation. If there is a gap, Chinese entrepreneurs are curious about it and more determined to close the gap.

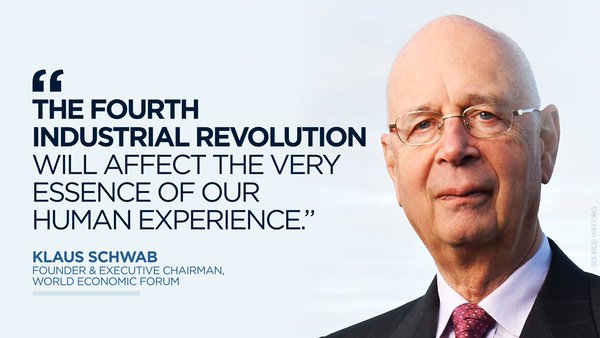

With these highly adaptive characteristics, Chinese tech companies are embracing new and emerging technologies, and China as a whole is at the front seat witnessing the Fourth Industrial Revolution – the merging of physical, digital and biological means. With technologies such as AI, IoT and Blockchain are here and 5G coming just around the corner, the Chinese are significantly embracing them to enable the next generations of innovations.

Going forward, we expect more tech-enabled innovations driven by heightened organizational curiosity from China. Though it is a universal phenomenon that the bar for success remains high, given the scale of the China market, its fast growth, its increasing prevalence of various forms of technologies and the prowess of its “three-layer duality” paradigm, the “odds of making it” are expected to be on the Chinese side. China’s path towards an innovative economy will inevitably involve many ups and downs, perhaps at times becoming quite turbulent and wasting some resources. However, one should acknowledge China’s consistent drive toward better livelihood for its people and a “community of shared future” for the humankind. At the heart of it, the source of this inspiration is the intrinsic curiosity of its organizations.

咨询的关键是quality。这包括质量与素质。优秀的咨询顾问确保工作的质量做到极致。这需要他本身拥有良好的素质。多读、多思考、沉下来,心要静。凡事以客户为中心、以团队精神为纽带。

多级跳是当今时代企业发展战略的重要指导框架。但多级跳并不是盲目的乱跳,甚至不是从某业务跳到另一业务而已。成功的多级跳战略者首先是对未来的主要发展趋势产生㓊察,然后从洞察之中发掘了能够改变或可创造游戱规则的机会。跳或不跳是基于战略者对机会带来的机会大小与自己目前能力的对比中作出比较后的判断的结果。

China Daily Global

Updated: 2019-05-27

The Hurun Research Institute, which compiles lists of China’s wealthiest individuals, released the Hurun Greater China Unicorn Index 2019 Q1 along with the Hurun China Future Unicorns 2019 Q1 on May 7.

According to Rupert Hoogewerf, chairman and chief researcher of the Hurun Report, which is a research, media and investments business, the total number of unicorns-startup companies valued at $1 billion or more-in China has reached a record 202, possibly the highest across the globe.

These Chinese unicorns include Alibaba’s financial technology affiliate Ant Financial, which is valued at $150 billion, and ByteDance, an internet company behind machine learning-enabled content platforms like TikTok (also known as Douyin) and Toutiao.

Tech startups today have not been able to replicate the financial success of well-known tech giants such as Google, Facebook and Alibaba. For example, China overtook the United States in AI investment in 2017, but around 90 percent of the AI companies were unprofitable.

This phenomenon is not exclusive to China. Some of the biggest names around the world have yet to make money, such as the publicly listed electric car maker Tesla and music streaming company Spotify, which are losing billions. Ride-hailing platform Uber lost $1.8 billion last year, but still made its debut on the New York Stock Exchange this month.

Although there are many startups that are unprofitable, it is probably unfair to compare established tech companies with the internet unicorns of today. The nature of entrepreneurship implies that there will always be winners as well as losers, best illustrated recently by the dotcom crash.

So what is driving the rapid valuation growth of many internet startups that are still incurring huge financial losses? Favoring growth over profit, investors are embracing so-called “growth companies” like Amazon, the world’s third most valuable company despite pale profits. As capital is currently cheap, creating growth is more valuable than improving margins.

Why then, do some startups fail but some eventually succeed? First, many of those that failed were not able to address an essential need. The digital boom and fast money in the 2000s created plentiful space for first-generation technological companies, especially in sectors like e-commerce.

However, it is becoming harder for the current generation of tech companies to tap into that growth, since low-hanging fruit has already been taken.

As investors continue to search for the next Alibaba or Google and more unicorns appear, some might just need time to prove themselves, while others will simply be growing for the sake of growth without any prospects for profit.

“科技改变将给人们带来更多的有益的结果。对个人来说,他们的生活将会更加地便利。而对企业来说,在科技发展的助力下,他们将有更多的创新机会,发展新的产品、服务、甚至建立新的模型等等。”

在迈入21世纪后,科技爆发式的进步让世界变化加速。机器算力的不断提高、及物品的互联互通给人们生活的各个方面都带来了极大的改变,从人们的零售行为到大健康、智慧出行等等。即使在这个节点,算力的发展与革命也还未结束,科技带来的影响仍在不断地加速产业改变的进程。

随着科技的发展,越来越多颠覆性的科技,从物联网、人工智能(AI)到5G和区块链,都将改变我们的生活方式。在互联网蓬勃发展的十几年中,企业逐渐由IT(信息技术)企业转化为DT(数据技术)企业。IT主要关注的是企业内部的管理能力,建立良好的IT系统将大幅提升企业的内部能力,而DT则趋于向外的能力打造。随着科技的进步,飞快提升的算力让企业将无处不在的数据讯速地输送到企业中心,从而利用大数据帮助企业很好地做出决策。

科技改变将给人们带来更多的有益结果。对个人来说,生活将会更加地便利。而对企业来说,在科技发展的助力下,企业将有更多的创新机会,发展新的产品、服务、甚至建立新的模型等等。

在这样的变革中,企业所选择的战略尤为重要。由于过去的企业战略思考环境较为固定,企业管理者习惯用线性思维,在已经固化的环境中延伸,思考企业的未来。由于科技推动产业的变革,如今,企业家需要迅速改变来适应新环境。

在过去几十年的主流概念中,企业有两条竞争的道路,一种是多元化发展,涉猎多种领域,而另一种是凭借企业的核心竞争力,进行聚焦竞争。在科技对社会的影响力越来越大,市场环境变化越发迅速的时候,企业家需要转变思维模式,才能在快速变革的环境中存活下去。时代改变让很多问题变得不确定,在过程中,我看到,部分企业在这个瞬息万变的时代走出了与完全不同的第三条路,通过把握机会与能力的灰色地带,抓住了新的机会,成功“连续跳跃”。

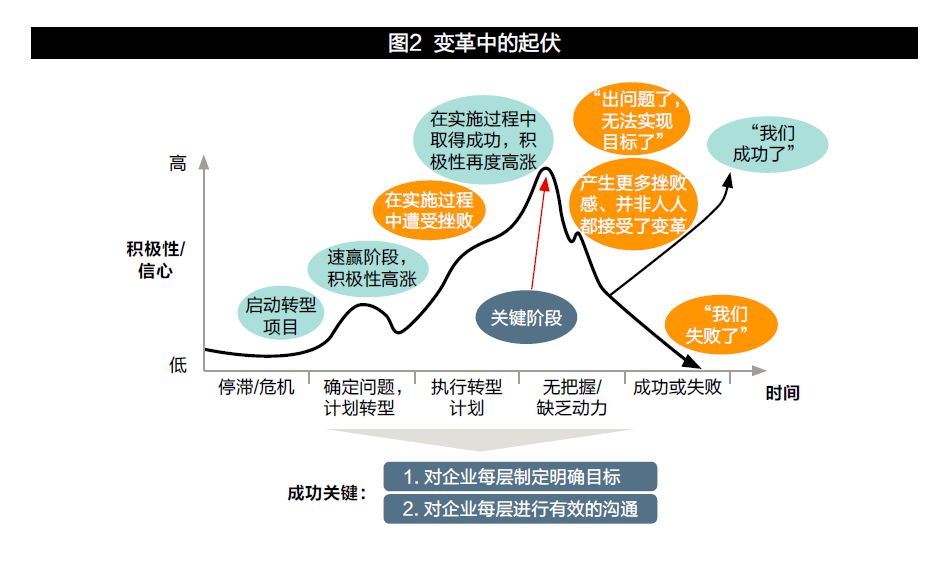

那么,企业在转变的过程中如何成功“跳跃”呢?许多因素将决定企业“跳跃”的结果,其中包括:他们是否能在“跳跃”的同时弥补自身的能力空缺,产生强大的势能,最后获得所需要的结果。或者,他们是否意识到了企业变革的几大基本元素,如:领导力、愿景和战略,及组织架构和形态。

组织的意识会影响企业的决策。通过与很多企业的合作,我发现企业像人一样,都被其意识所支配。在不知不觉中,潜意识支配了我们90%以上行为。大部分的企业失败往往是由集体的潜意识导致的。因为组织由上到下都没有建立良好的企业潜意识,所以最后走上衰落、最终失败之路。

领导者的角色也尤为关键。良好的领导者必须帮助组织建立自己清醒的意识,让他们对外界变化保持警觉。领导者需要不断地提出“我们是谁”这个问题,让组织拥有共同的目标。另外,由领导者所带领团队的执行力,将对最终成果起到至关重要的决定性。优秀的领导者很快就意识到团队执行力的重要性,并加以警惕和鼓励。马明哲就曾对此评价过“拥有执行力才能让你强大,一个人做事情快点,顶多叫执行,一百万人的同进退,那才是执行力”。

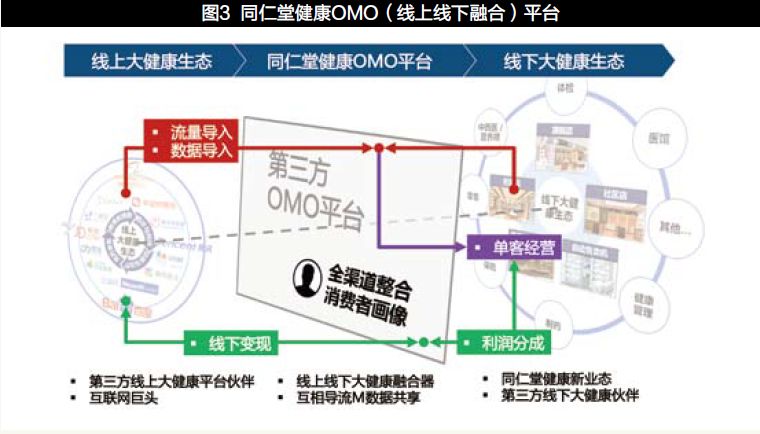

不仅如此,领导者还需要在变化莫测的商业战场上,带领员工着眼于未来。在科技的影响下,数字化变革已经带来了许多机会。在这个变革的时代,企业该如何改变思维模式,如何通过互联系统打造与消费者更紧密的连接,将对他们的发展起到不可或缺的影响力。正如高风咨询高级顾问黄林所说的,在这个科技推动产业变革的时代,领导者应该意识到,企业的发展策略应以客户为中心,打造其业务定位、用户定位、及战略定位,才能让公司持续发展。

首先,企业应该抓住科技进步带来的机会,发展以客户为中心的策略,打造“千人千面”的信息推送。在科技和算法蓬勃发展之际,企业应该精益求精,进一步分析消费者的行为、社交、交易消费信息和需求,围绕产品打造从产品到营销、服务的个性化全链路体系。

不仅如此,企业应着力打造业务定位、用户定位、及战略定位。在变革之际,改变思维模式,将电商作为首要销售渠道,并为之设计更适用于电商的营销活动。这样,企业才能利用线上线下销售平台的优势,为消费者打造沉浸式的服务体验。

另外,科技的发展给予消费者更多发声的机会,而企业也应该采取措施适应用户的新定位。在过去几十年中,传统企业早已习惯与消费者的单向沟通,通过各类媒介向消费者传播信息。但是,在互联网普及后,企业与消费者的双向沟通渠道越来越多。通过 AI 写作、语音交互等功能,企业不仅可以更精准地与客户沟通,了 解客户需求,客户也可以从更多渠道发表自己对产品的看法。从另一方面,企业也可以通过互联网,基于更多消费者的个人信息与消费行为数据进行数据分析,更好地与客户进行一对一的沟通与交互,给予客户个性化、定制化的服务。

随着消费升级的全面展开和新零售的到来,传统企业不仅需要展开线上销售服务,更需要对战略定位做出及时调整,将电商或互联网平台置于企业战略的重心。随后,可以通过分析客户信息、实现人群洞察、市场评估成功实现制造端的千人千面。

在科技推动产业变革的时代,企业家需要重塑观念模式,拥抱变革,及时调整领导力、愿景和战略,及组织架构和形态,将企业的不良潜意识通过集体修炼转成清晰的正面意识,用“心”来做对的事,才能在新的时代里继续发展下去。

原文发表于《亚布力观点》(2019年4月刊)并保留所有权利

(注:本文图片均来自网络)

Dr. Edward Tse’s article was published in his regular column on Brazil’s HSM Management Magazine. In this article, Dr. Tse discussed how China’s system works to the favour of the country’s tech-enabled business innovations.

English Version

China’s Age of

Innovation and Game-Changers

Branded for decades as a “copycat nation”, China has now re-emerged as a global epicenter of business and technological innovations. The internet and tech sector – ranging from ride-hailing to e-commerce, robotics and artificial intelligence – grew 20 percent in 2018 to a total of 142 billion USD value. Two Chinese companies, Tencent and Alibaba are now among the top ten of the world’s most valuable companies. China has also become the second-largest birthplace of unicorns (unlisted companies valued at or above US$1 billion), and has filed the largest number of domestic AI-related patents, trumping Silicon Valley by as much as seven times, according to CB Insights.

Several drivers contribute to China’s rapid transformation. First, a “why not me” mindset drove the Chinese entrepreneurs who, realizing the huge gap between China and the rest of the world, in particular during the early years of China’s reform and opening, want to show that they too could succeed.

Second, as its economy transformed, China’s once-hidden societal pain points became exposed; coupled with the prevalence of technology (especially the wireless internet and smartphones), these pain points provided the breeding ground for innovations.

Third, while their state-owned counterparts are typically slower in adaptation, privately-owned entrepreneurial companies rose to the challenge and took on the opportunities. At the same time, China’s massive market allowed companies to rapidly scale up, and its hyper-competition spurred companies to continuously innovate.

Finally, Chinese companies have benefited greatly from the vast pools of venture capital and angel investors. Many of the investors, including both foreign and local, have also benefited from exceptional returns on their investments in China.

The innovative ecosystem arose from China’s unique “Three-layer Duality” development model. At the top, the central government’s guiding hand sets goals and directions for the country, giving the rest of the country clear targets to follow. At the grass-roots level, the private sector entrepreneurs have re-emerged since the end of China’s Cultural Revolution and is a major force in driving the growth of China’s economy. And, In the middle, China’s local governments channel their resources into national and local priorities, often collaborating closely with entrepreneurs who bring innovative ideas to bear. Local governments often compete with each other, but they also cooperate within regional clusters. Though the model occasionally suffers from glitches, in general, the coexistence of private and state-owned players provides tremendous resilience for the growth of both sectors.

China’s path towards an innovative economy will, however, not simply be a straight line; it will inevitably involve many ups and downs. The probability of successful innovations for anyone – either large corporate or startups – is low. Nonetheless, with the scale of the China market, its relatively fast rate of growth, the increasing prevalence of various forms of technologies such as artificial intelligence, Internet-of-Things, blockchain technology and 5G, as well as the prowess of its “three-layer duality” paradigm, one would expect that China could continue to drive innovations in significant ways.

By Edward Tse | China Daily Asia

Agile Chinese entrepreneurs are emerging as business thought leaders with their ‘multiple jumping’ expansion strategy

Ever since Deng Xiaoping hit the gas pedal on China’s economic reform when he made his famous Southern Tour to Shenzhen in 1992, companies in China — big and small — have been looking for ways to better manage, develop strategies and capture value.

For the first 30 years of the People’s Republic of China, the country was organized under a planned economy. There was no notion of companies, shareholder value, management or strategy. So when China’s economic reform started and when entrepreneurs first emerged, they by definition would not have had any formal education in modern management or prior experience in actually running a company.

The rapid growth of China’s market and the emerging competition drove many of these entrepreneurs to look for ways to better plan and manage their businesses.

The first wave of management consulting firms and business schools came to China from the West in the early to mid-1990s, and brought along established knowledge, theories and frameworks. Chinese businesspeople were attracted to these new ideas as they searched for ways to help run their businesses better.

In the West, from the 1970s to 1980s, the notion of conglomerates was dominant. Companies like ITT and Tyco in the United States and Hanson Trust in the United Kingdom grew into large amalgamations of businesses, often across a range of unrelated sectors.

The notion was that “big is good”. After a while, the capital market decided that conglomerates were not such a good idea after all, because of the lack of synergies across the various businesses.

In 1990, Gary Hamel and CK Prahalad from the University of Michigan published an article called The Core Competence of the Corporation, focusing on this trend. They argued that well-performing companies compete based on their strengths, or what they called core competences or capabilities. This theory caught on quickly in the Western business community and became the governing thought for companies’ strategy formulations.

Today it is still the case. Using this theory, the capital market suggests that companies should focus on their areas of strength. And, by implication, companies should not expand arbitrarily beyond their areas of strength.

When management consulting firms and business school academics first came to China, they brought along these concepts and used them as guiding frameworks to advise Chinese clients. However, the Chinese executives, while intrigued, quickly came to the realization that something was missing.

While useful, these frameworks could not quite explain the overall context of doing business in China. The consultants and academics also quickly realized that business in China is somewhat different, although they could not explain exactly what the difference was.

In the meantime, the external operating environment was evolving fast, both in the world and particularly in China.

China’s fast economic growth, its gradual but consistent transition from planned economy toward market economy, the emergence of highly intensive competition in the open sectors, and the increasing prevalence of technology and the availability of angel investing and venture capital funds, all contributed to the emergence of waves of entrepreneurship and innovation in China that the country had not seen before.

In their search for growth strategies, these Chinese entrepreneurs were typically fast and agile. Some of them developed diversified conglomerates, and there were others that decided on a narrow focus, taking the core competence approach. The results have been mixed.

Interestingly, some of them, through trial and error, discovered a third way of strategy development. We call it “multiple jumping”.

When these entrepreneurs see new opportunities evolving, even if they do not have all the capabilities to fully operate the new business, they decide if they should jump over or not.

So far, some of the companies that have jumped have been successful in latching onto the new business sector. Often, they will repeat the process when newer opportunities turn up. When these companies jump, they try to fill their capability gaps either through their own efforts or by collaboration with other companies, or by using both approaches.

This multiple jumping approach to strategy is different from a conglomerate approach because, despite their involvement in multiple sectors, these companies generally keep their original heritage as their core.

On the other hand, multiple jumping clearly defies the core competence approach, because these companies are willing to enter new areas of business without having the expected core competences established.

So, this multiple jumping approach is another way to think about strategy beyond the conglomeration and core competence approaches. We call it The Third Way.

It provides another way for companies to decide how they should develop their business strategies in a fast-growing, discontinuous operating environment abounding with fertile opportunities.

A prime example of a company that has successfully adopted this approach is Alibaba, which has interests in industries including healthcare, the media and consumer finance as well as its core e-commerce business. Coincidentally, US companies such as Amazon and Google have also grown through this approach.

As China’s operating environment continues to rapidly evolve, innovation and entrepreneurship are thriving. Companies are looking for even more inspiration for growth. Many entrepreneurs continue to look at the West, especially at the US, for inspiration in technology, management and investment models. Some are also examining Chinese historical philosophies for guidance.

Today, in addition to a growing number of consulting firms, business schools and training companies in China, many corporations have also set up their own “universities” or “academies”. Business executives, successful or not, are eager to share their experiences in running businesses and some have turned into modern philosophers.

Conferences and seminars organized around themes of business, innovation and transformation take place regularly in different cities throughout China. Airport bookstores, where business traveler traffic is heavy, stock a proliferation of business books. Videos showing various “experts” talking about the secrets of successful business are now commonplace.

Social media, in particular, has become a popular medium for people to share their points of view — freely critiquing others’ successes and failures, with or without any real business experience of their own. Online celebrities emerge from the corners and some have captured many eyeballs with their opinions on business trends and remarks on individual businesspeople.

A fair number of Chinese entrepreneurs are still relying on brute force and guanxi (relationships) to run their businesses, but increasingly, some regard knowledge as the key source for building their companies’ sustainable competitive advantages. To this end, they actively search for new ways of building businesses.

On the surface, these attempts may seem unsystematic and perhaps some will prove futile. But some are creating new patterns that could become cutting-edge thinking, and they could form a new cornerstone for business thought leadership that will bring about future inspirations for the rest of the world.

Edward Tse is founder and CEO of Gao Feng Advisory Company, a global strategy and management consulting firm with roots in China. He is also the author of China’s Disruptors (2015).

Original published by South China Morning Post on May 6, 2019. All rights reserved

Embroiled in a trade war with China, the Trump administration, in February, signed an executive order aiming to spur the development of artificial intelligence, in response to the rising fear in academia and government that the US is losing the race for global AI leadership to China.

Such fears are not entirely unfounded. China has a well-funded commitment to the development of AI. The leadership in Beijing has outlined its ambitions in various development plans, including the initiative to build “advanced manufacturing”. According to Tsinghua University’s China AI development report, released last year, China has secured a leading position in the AI echelon in both technology development and market applications. China ranked first in the total number of AI research papers and AI-related patents, and second in terms of the size of its AI talent pool.

There are several key drivers of China’s progress. First, it enjoys a fundamental system advantage. In the past four decades since its “reform and opening up”, China has somewhat unconsciously evolved its own “three-layer duality” development model. At the top, the central government’s guiding hand sets goals and directions for the country, giving the rest of the nation clear targets to follow. At the grass-roots level, private-sector entrepreneurs have re-emerged and become a major force in driving economic growth.

In the spirit of driving the development of advanced manufacturing, provinces and cities across China have instituted preferential policies for AI start-ups. For example, Tianjin, a major port city in the northeast, launched a US$16 billion fund last year to bolster the local AI industry. Tech companies collaborate with local governments on AI initiatives such as smart city, health care and autonomous driving. Alibaba’s ET City Brain project uses AI to tackle traffic jams, reducing traffic delays by 15.3 per cent in parts of Hangzhou, the city in which Alibaba is headquartered.

Second, the massive size of the Chinese economy allows companies, especially AI companies, to rapidly scale up. China now boasts more than 800 million internet users, roughly 58 per cent of its total population and three times larger than the number in the US. According to the China Internet Network Information Centre, 98 per cent of them are mobile internet users. The large online population generates an abundance of data, on which algorithms can conduct large-scale research and experiments much faster and more intensely than is possible in the West.

For better or worse, Chinese are more relaxed about data privacy than Westerners, at least for now. What may be viewed as a violation of privacy by some could be advantageous for AI developers wanting to extract a large amount of data. This situation allows Chinese AI developers to achieve more accurate machine learning models in areas such as facial recognition, voice and gesture recognition, consumer behaviour analysis and robotics process automation.

Third, a “why not me” mindset drives Chinese entrepreneurs, who are eager to show that they too could succeed. Today, younger entrepreneurs view their successful predecessors as role models and want to replicate their success. China’s hypercompetitive environment harbours cutthroat commercial activities and transformative business models, allowing the fruits of AI to quickly spread across the economy.

China tops the list of the number of active AI companies and venture capital investment. Leading players, such as Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent, are investing heavily in AI technology. For example, in 2018, Tencent invested about US$120 million in Shenzhen-based humanoid robot designer UBTECH Robotics. Baidu not only poured US$1.5 billion into its Apollo Fund for autonomous driving, but has also developed a neural-network-based machine translation system that has at times achieved speech recognition accuracy higher than that of humans.

Rising start-ups, on the other hand, have created tremendous value. Among those is the previously mentioned UBTECH Robotics, the world’s highest-valued AI start-up at US$5 billion. ByteDance, the company behind AI-powered news and information content platform Toutiao and popular short video platform TikTok, has grown 230 per cent in revenue in the past two years.

While the Chinese tend to favour applications of existing technologies, the West focuses more on the science and infrastructure behind AI. Fundamental research is high-hanging fruit that would take much more time and risk to achieve results than commercial applications.

However, there are signs that this is also beginning to change. The Chinese government is planning support for AI education, research and development. One of the newer projects, the Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan, offers a forward-looking blueprint for basic theory and common key technologies. Another project on brain science and brain-inspired research is comparable to Europe’s Human Brain Project and the US’ BRAIN Initiative. Inevitably, some of these technological experiments will fail but others will make it. It is through experimentation that progress can be made.

Should we simply focus on the winner of the “race” between China and the US? “Race” implies a zero-sum game, as if the two countries must treat each other as “strategic competitors” and acknowledge a mutual threat. While there is competition, there is also plenty on which to collaborate. In today’s increasingly interconnected world, we need organisational means to address issues that transcend national borders, including those of AI development and governance.

Some level of collaboration in AI among American and Chinese researchers is already under way. For example, the Partnership on AI, an organisation founded by Amazon, Google, Facebook and others, announced last year that Baidu would join its network. The consortium of companies recognised the importance of global discussion around the future of AI and showed a desire to counter the arms-race narrative. There is a need for China and the US to focus more on similarities and common goals for the betterment of the entire world.

Picture Source | Google

刚刚通过的《中华人民共和国外商投资法》(下称《外商投资法》),是一项将取代现有外商独资、中外合资企业管理制度的新法律。为了应对不断变化的全球商业环境,进一步满足经济开放的需要,该项法律增加了许多致力于为国内外企业创造公平竞争条件的新规定。

《外商投资法》不容许“强制技术转让”,“强制技术转让”是一直以来被美国政府方面用以推动中美贸易摩擦的主要理由之一。 新法律还强调保护外国投资者和外商的知识产权,鼓励技术合作。其他激励政策包括建立具有税收和商业制度吸引力的经济特区、允许利润与资本收益外移,并缩短外商投资项目的负面清单。除此之外,中国还将鼓励外国投资者积极参与国有企业的“混合所有制”改革。

这些政策变化对于外国投资者和外商来说无疑是个好消息。长期以来,不少外企一直抱怨在中国缺乏市场准入的机会。可是如今,对于许多外国跨国公司而言,中国即便不是最大的市场,也已成为它们最大的市场之一。即使对于一些还未进入中国市场的公司来说,缺席了中国市场,它们全球的商业模式也不完整。然而,我认为仅仅依靠政策和法律层面的改革并不能确保外企们最终能在中国市场上取得成功。

在过去的十多年中,中国的市场环境早已发生了翻天覆地的变化。中国本土企业(不论是国有企业还是民营企业)的实力实现了大幅的提升,不少早已成为外国跨国公司强劲的对手。不可置疑的是,即便在一些领域(如:奢侈品、高端汽车、原创药等),外国跨国公司依旧占有较大的优势和份额,但中国的本土企业已经在电商、金融科技、移动出行等新兴市场领域上成为主导者。

在这些来自中国的竞争对手中,有一些是大型的国有企业,尤其是在较多依赖国家和政府政策支持的行业,如能源和电信等。然而在其它更加开放、公平的领域(如:快消品、零售、消费电子等)中,大多数最具竞争力的公司则是由民营企业家创立的。领先的民营公司均高速发展,并具有极强的敏捷性和创造力。

这些现象是中国过去几十年改革开放和商业创新兴起所取得的成效,并还是方兴未艾;是日益普及的技术与地方、中央政府政策及基层创业的综合结果。通过发展新的互联网模式和技术——从共享出行到电子商务、机器人和人工智能,中国的企业家正逐渐摆脱中国过去“模仿者”的形象。

令人遗憾的是,大多数在中国经营的外国跨国公司很大程度上只是中国创新的旁观者,没有大幅度参与中国创新的历程。但中国近年来充满创新并快速变化的商业环境迫使它们对此做出相应的反应。例如,在汽车出行行业,诸如电动化、自动驾驶、智能车联网及出行服务等变革趋势推动了全球领先的汽车制造商和出行服务提供商进行调整和变革。不仅如此,不少外国跨国公司也渴望通过中国创新模式,诸如微信、支付宝等在线生态系统,与中国消费者建立更密切的联系。

在中国经营的外国跨国公司如今也意识到它们需要向中国学习,在中国,乃至世界的市场上不断创新。但这并非易事,因为有此战略的外国跨国公司需要将中国视为创新的温床和战略的核心。要做到这一点,它们必须将中国置于其全球战略的核心,而不仅是其众多地理区域的其中一个(即便是其中很重要的一个)市场。

目前为止,大多数外国跨国公司的“本土化”依旧做得比较表面,就是在全球总部或是地区总部制定战略规划,安排中国本土的管理者执行下达的任务。这种决策过程和模式不仅不够迅速,并且忽略了整个中国市场环境的快速变化。这些变化很可能对中国乃至全球的战略都产生重大影响。要想达到真正的“本土化”,外国跨国公司应在中国安排具有战略思想能力的领导者,给予足够的决策权和资源,从而让公司在中国深入地了解和适应其独特的商业环境。

新的法律标志着更加友好的环境,将使外国跨国公司的潜力在中国得以释放。在这个不断变化、竞争愈发激烈的环境中,创新尤为宝贵。

近年来,越来越多的外国跨国公司开始意识到这一点并进行改变。起初,它们仅在中国试水,将国外持之以恒的产品或商业模式带到中国来,不做任何调整。经过一段时间之后,当它们逐渐意识到中国的特点从中积极学习,会开始改变自身,逐渐地适应中国市场。近年来,越来越多的外国跨国公司开始汲取中国创新者的经验,采取以中国为核心的本土化战略,积极与当地公司携手搭建庞大的生态系统,以便真正立足于中国市场。

对于中国的企业家与投资者而言,新的《外商投资法》带来的既是挑战也是机遇。更加开放的中国市场将涌入更多的竞争者,让市场竞争更为激烈。中国企业家必须保持其源源不断的创造力才能在这个瞬息万变的环境中保持自己的竞争力。与此同时,中国本土企业也需保持开放的态度,尝试探索与外商合作的可能性。尽管部分外国跨国公司在中国依然存在水土不服的状况,但在一些领域上(如:核心技术、企业管理、品牌、文化与价值观等),比较优秀的外企依旧有许多值得中国企业借鉴和学习的地方。

对投资者来说,该法律也带来了许多机遇。在适应中国独特环境的过程中,一部分外国跨国公司会对自身业务进行调整,出售一些业务单元。在资本的支撑下,本土的投资者可以利用外企的基础(如:知识产权、产品、品牌等)和自己对中国市场的了解进行投资,通过庞大的潜在市场来提升公司的价值,从中得到相应的回报。

新的法律标志着更加友好的环境,将使外国跨国公司的潜力在中国得以释放。在这个不断变化、竞争愈发激烈的环境中,创新尤为宝贵。不论是身处中国的外国跨国公司,还是中国本土的企业,都需时刻依据市场环境和宏观政策及时调整战略,提升竞争力,从而把握机会,获得更大的优势和利益。

原文发表于《亚布力观点》(2019年4月刊)并保留所有权利

(注:本文图片均来自网络)

What Drives Business and Innovation in China?

What Drives Business and Innovation in China?

商业的根本在于对客户抱有“以客户为中心”的理念

有限的游戏 vs 无限的游戏

今年来,美团收购摩拜单车,美团、高德和携程进入网约车市场等新闻冲击着媒体的热点。企业的核心与边界问题再次成为大家热议的话题。

此前,一篇名为《王兴的无限游戏》的文章在此问题上进行了讨论,大意如下:

美团创始人王兴曾说:“太多人关注边界,而不关注核心。”关于业务和竞争,他认为不要期望一家独大,也不要期望结束战争,所有人都要接受竞合才是新常态。同时,他认为太多思考边界和终局是错误的。既然大多数人的思考都是错误的,那什么才是正确的思考呢?答案或许隐藏在一本名为《有限和无限游戏》书中,有限的游戏以游戏的终结为目的,旨在以参与者的胜利终结一场比赛;而无限的游戏是有限游戏的延伸,没有终结,游戏本身就是对边界的不断探索。而王兴的思维也正是来源于此,我们急需一个关于“游戏观”的转变,即从有限的游戏转向无限的游戏。

在今年二月的亚布力中国企业家论坛第十八届年会的《激活:个体与组织》会议上,我曾对北京大学国家发展研究院的陈春花教授就组织的边界问题进行提问:“一个组织在一个新的时代中,它的组织边界在什么地方?”陈教授认为,“顾客在哪里,你的组织边界就在哪里”;“提供这个边界的能力可能不是你自己,你要跨界,你要跟别人合作,所以你自己的边界可能就要先被打开。”

战略的第三条路:打破战略的困局

去年,美团创始人王兴和携程联合创始人梁建章以及饿了么创始人张旭豪,关于“企业走多元化之路和专注之路哪个更好”的问题进行了隔空交锋,成为商界关注的一个热门话题。王兴的观点在于,企业不应太多受限于边界,应借助多业务发展和整合来释放更多红利。梁建章、张旭豪的观点则是多元化不利于创新,中国企业更应考虑专业而非多元化发展。

王和梁张之辩的背后,反映了长期存在于广大中国企业家心中的一个非常普遍的困惑,那就是对企业发展来说究竟多元化发展好还是专注好。我们称之为“战略的困局”。

在过去三十年间,核心竞争力理论(即“专注”理论)和多元化集团式经营理论几乎占据着典型西方商学院和咨询公司企业战略的全部。

这些理论都只是考虑企业的内部能力,对外部环境变化几乎完全没有涉及。而全球宏观环境却在过去的5到10年间发生了很大的变化,特别是中国呈现出了快速的增长,及美国尤其是西海岸创新科技的涌现带来了新发展。新的背景下,有两大驱动力在改变和重塑新的格局:一是中国市场的崛起,二是科技的迅猛发展。

科技和数据是企业在连续跳跃和调整边界过程中的主要促进因素

在这种新的背景下,多元化集团式经营和依托“核心竞争力”为本的“专注”化经营已经不能给企业家提供全部的答案,战略的第三条路则弥补了这个空白,我们称之为连续跳跃战略。连续跳跃是指企业面临新的(往往是非线性的)发展机会时,不再囿于现有能力所限定的范围,而是通过不同路径弥补能力空缺,进而抓住新的机会实现延续性的跳跃式发展。当企业通过自建、并购或组成生态系统等多种方式成功跳跃后,它会在新的领域不断地重塑业务边界,不断地进行动态调整。在这动态调整过程中,企业的边界会扩张、膨胀,亦有可能收缩。而谁是你的客户亦会因边界的改变而改变。没有企业拥有无限的资源和能力(这里指调动生态系统的能力)。故此,企业的边界是不会无限扩张的。

当市场上出现新的机会时,企业往往会考虑要不要“跳过去”来抓住这些新的机会,即便它们并不拥有经营新业务所需要的所有能力。有些企业跳跃并成功地跳了过去;亦有一些企业曾尝试却没跳成功。跳跃成功的关键是什么?它是机会与能力之比。这里的能力并不只是企业自己的能力而已,它亦包含企业自建、并购或组成生态系统等隐性能力。

科技和数据是企业在连续跳跃和调整边界过程中的主要促进因素。能够掌握好这些因素而成功,成为大数据型数字竞争者都会遵循以下四大核心原则:

一、无处不在(Ubiquity):海量的客户覆盖,在几乎所有主要线上触点上实现与客户的直接接触。商业活动同时存在于线上和大量线下,能够实时实地为用户提供服务。

二、单客经营(Segmentof One):针对每一个客户的个性化需求,提供定制的产品与服务组合,提高体验感。例如通过数据分析,实现定向推送推荐。

三、全面连接(Connectivity):通过生态系统与客户保持不间断的连接(移动智能设备、物联网等)。

四、互联互通(Interactivity):借助社群把具有相同爱好和诉求的客户聚集起来,进行相互交流,从而增加对品牌的归属感和粘度。

边界的动态调整

美团能够通过收购摩拜,进入网约车领域等行动来调整边界,是因为它做到了以上的四大原则。它以科技和数据作为核心,通过不断的连续跳跃,构建了庞大的生态系统,重塑了企业的边界,亦扩大了自己的用户范围。简而言之,美团玩的是一套“改变游戏规则”的战略。

商业的根本在于对客户抱有“以客户为中心”的理念。许多人都很羡慕亚马逊的业绩表现,但有多少企业和企业家真正理解贝索斯所推崇的“对客户的疯狂热爱”(Customer Obsession )的信条呢?

今天,谁都说要做亚马逊,要“以客户为中心”,但实际却不一定做得到,不少企业们在对客户为中心的理解和实践往往有着巨大的差距。对不少企业来说,“以客户为中心”仅仅只是一句口号而已。

你的边界在哪里?是你在机会和可获取能力之间的选择和两者之间博弈后出现的结果。而谁是你的客户亦是如此。

原文发表于《亚布力观点》(2018年4月刊)并保留所有权利

(注:本文图片均来自网络)

关于作者:

谢祖墀博士(Dr. Edward Tse)是高风管理咨询公司(Gao Feng Advisory Company)的创始人兼首席执行官。中国管理咨询业的先行者。过去的20年里,他创立并领导了两大国际管理咨询公司在大中华区的业务。外界评价他为“中国的全球领先商业战略家”和 “谢博士之于中国企业界就如大前研一之于日本企业界”。他曾为数以百计的公司(总部设在中国及其它地区)咨询过所有关键战略和管理方面的业务,涉及中国的各个方面和中国在全球的地位。他还为中国政府在战略、国有企业改革和中国企业走出国门等方面做过咨询。他已发表200多篇文章并出版了4本书,其中包括于国际获奖的《中国战略》和《创业家精神》。谢博士获得了加州大学伯克利分校工程学博士、MBA以及麻省理工学院的工程学学士、硕士。

文| 谢祖墀

对于中国企业来说,领导者要做好量子计算在不久的将来对行业产生重大影响的准备,并逐步开始接触量子科技,鼓励研发人员利用量子计算寻找突破。毋庸置疑,提前做好部署的企业将取得领先。

最近有一些客户来询问我们有关量子信息科学的发展的启示。高风咨询团队做了一些研究的工作,在这文章中我们总结了研究发现的重点内容。有什么不对之处,请指正。

正如人工智能最初进入人类的视野一样,对于“量子信息”,大多数人缺乏准确的概念,也难以分清与之相关的企业都在做什么。而对于企业而言,如何在今天这个指数发展的时代,抓住量子信息的契机,并最终取得持续的成功,亦是难事。量子信息是量子力学与信息科学最尖端领域的结合,在通信和计算方面将会对未来企业运作有至关重要的影响。

简单而言,量子信息领域主要包含信息的传输和计算,即量子通信和量子计算。最先走进产业化的就是量子通信技术。当今社会不断加剧的信息安全问题促使了人们发展这种不同以往的高度保密和安全的通信方式。

量子通信不仅可以应用于国家级安全通信,也适用于国民经济重点领域的数据传输和加密。因此,世界各国都开展了量子通信网络的建设,而在这方面的建设和研究上,中国目前已经走在世界的前列。早在2013年,我国就启动了全长2,000多公里的量子保密通信“京沪干线”工程建设。该项目连接北京、济南、合肥、上海等多个城域网络,按计划正逐步接入金融、电力系统、大数据互联网企业等用户。2016年,中国发射了人类历史上第一颗用于量子通信研究的“墨子号”量子科学实验卫星,开启了全球化量子通信时代的大门。2018年初,“墨子号”量子卫星首次实现了北京和维也纳之间约7600公里的保密通信。该成果被美国物理学会评为2018年度国际物理学十大进展之一。中国科学技术大学物理学家陆朝阳曾表示:“如果首颗卫星表现不错,中国肯定会发射更多。”

中国科学技术大学教授、中国“量子之父”潘建伟也曾提及,量子通讯行业隐藏着巨大的商业机会,“京沪干线将带动整个产业链的发展,特别是在核心元器件国产化和相关标准制定方面。”除此之外,随着量子通信网络的不断发展,量子通信网络运营商和应用服务需求也将快速上升。根据有关研究所估计,量子通信市场规模在未来3~5年内,有望达到100~300亿元。

另一方面,许多专家相信,量子计算将在未来彻底改变信息处理的方式,带来新一轮的信息革命。随着当前互联网数据的日渐复杂和庞大,传统计算模式的增长正趋近瓶颈。而新时代的量子计算机可能只需几秒就能解决传统计算机需要花费数年时间计算的问题。当云计算难以满足庞杂的计算需求时,量子计算机的先进性将助力云计算走出困境,推进整个大数据产业的发展。在未来,量子计算很有可能整合不同平台的数据库,实现数据的完全共享,创造出一个崭新的、系统的量子云生态圈。

从政府,到科研机构和各类企业,都逐步在量子力学领域投入了巨大的资金和人力资源。在《“十三五”国家科技创新规划》中,量子计算已被列入科技创新2030重大项目。2015年,中国科学院和阿里巴巴集团在中国科学技术大学联合成立了“中科院-阿里巴巴量子计算实验室”,这是中国民间资本首次全资资助科研单位进行基础科学研究。欧美等发达国家也都大力投入量子计算技术的研究。IBM在2016年上线了全球首例量子计算云平台。2018年,“Google量子人工智能实验室”宣布推出全新的量子计算器,声称其运行速度比传统处理器快1亿倍。

量子计算的商业热潮已悄然开始。参与量子计算的商业公司主要可分为四类:

第一类是端到端服务提供商,一般为IT或者工业巨头,代表企业有IBM,Google,微软,阿里巴巴;

第二类是硬件系统玩家,代表企业有Intel;

第三类是软件服务玩家,代表企业有QC Ware;

第四类是专业领域玩家,大多数是由科学实验室转化、分离而来的创业公司,致力于利用量子计算给不同公司提供细分领域的解决方案。

整个量子计算生态系统是不断变化的,暂处于动态平衡状态。各类玩家之间的界限比较模糊,将会有越来越多的交集,部分玩家甚至有机会打破生态平衡。现在就已经有许多硬件系统类玩家在朝产业链的应用层发展,触达服务层,试图进行纵向整合。

量子信息技术的发展已经是一种全球的趋势和国家的重点战略部署。

尽管大面积的量子计算应用看起来似乎还需要一些时间,但我们已经开始看到部分功能有限的量子计算在不同行业中的影响。全球最大的汽车集团大众汽车利用量子计算技术来优化交通方案。该公司与量子计算创业公司D-Wave Systems合作建立专业团队,收集了北京约10,000辆出租车的数据,通过量子计算云平台计算并模拟出城市最佳路径,用于缓解城市交通堵塞的压力。除此之外,世界上最大的化工厂BASF和民航飞机制造商Airbus等也将量子计算应用于行业之中。正如D-Wave Systems的首席执行官,维恩·布朗内尔(Vern Brownell)所说:“我们正处于量子计算时代的黎明。我们相信,我们正处在提供传统计算无法提供的功能的转折点。几乎在所有学科中,你都会看到量子计算机产生了这种影响。”

虽然量子计算不是对所有人和企业都有意义,但其带来的量子计算平台、工具和算法,对于行业工作者而言,有望推进研发进程,拓展业务边界。很多原本传统的企业,都已经开始和量子科技相关企业的进行跨界合作,构建量子生态系统,而这样的机会在未来将会越来越多。对于中国企业来说,领导者要做好量子计算在不久的将来对行业产生重大影响的准备,并逐步开始接触量子科技,鼓励研发人员利用量子计算寻找突破。毋庸置疑,提前做好部署的企业将取得领先。

量子信息技术的发展已经是一种全球的趋势和国家的重点战略部署。随着科研技术的进步,市场日趋成熟,将引领该技术的产业化进入新阶段。

原文发表于《亚布力观点》(2019年3月刊)并保留所有权利

(注:本文图片均来自网络)

By Edward Tse

Levelling the Field: Foreign Firms will Need to Raise their Game in China with New Investment Law

Original published by South China Morning Post on March 23, 2019. All rights reserved.

China has just passed a new law that will replace existing regulations on wholly foreign-owned enterprises and on joint ventures involving overseas companies. In response to changing global realities and the need to further open up its economy, the new law includes many stipulations that aim to foster a level playing field for foreign and domestic enterprises.

Forced technology transfer, one of the main issues driving the US-China trade war, will now be banned. The law also emphasises intellectual property rights protection for foreign investors and encourages technological cooperation. Other incentives include establishing special economic zones with attractive tax and business regimes, allowing the transfer of profit and capital gains out of the country and shortening the list of prohibited investment projects. Moreover, China will encourage foreign investors to participate in the mixed-ownership reforms of state-owned enterprises.

These changes are certainly welcome news for foreign businesses and the circle of politicians and lobbyists in Washington, who have long complained about a lack of market access in China. For many foreign multinational corporations, China has become one of their largest markets, if not the largest, in the world. Even for those that are only considering first-time entry, such as cross-border payment or credit card businesses, their global business models wouldn’t be complete without a credible presence in China. However, though a favourable signal, these legal changes cannot guarantee foreign multinationals success. The market conditions in China have evolved quite significantly over the past decade.

A major shift in the past decade has been the emergence of Chinese companies as bona fide competitors to foreign multinationals. Whereas foreign multinationals still enjoy advantages in sectors such as luxury goods, premium-branded cars and patented pharmaceuticals, Chinese companies have become serious competitors in e-commerce, fintech, fast-moving consumer goods, appliances and logistics.

Source: SCMP

Some of these Chinese competitors are large state-owned enterprises, especially in sectors that require strong state roles, such as energy and telecommunications. However, the most formidable, and the majority, are private companies marked by their speed, agility and creativity, in sectors where the playing field is practically open and even.

This phenomenon is part of the rise of business innovations in China over the past decade, as a combined result of increasingly prevalent technologies, local and central government policies and grass-roots level entrepreneurship. Ridding itself of the “copycat” stigma, China has nurtured a new internet and tech sector – ranging from ride-hailing to e-commerce, robotics and artificial intelligence – that grew 20 per cent in 2018 to a total value of US$142 billion.

Two Chinese companies, Tencent and Alibaba [the owner of the Post], are now among the world’s top 10 most valuable companies. Unicorns – unlisted companies that are less than 10 years old and valued at or above US$1 billion – are thriving. Ant Financial, a Chinese fintech company and an affiliate of Alibaba, is now the world’s largest unicorn with a valuation of US$150 billion. ByteDance, owner of Toutiao, a popular newsfeed app, and Tik Tok, a popular short video app, is valued at US$78 billion, ahead of the US-headquartered ride-hailing app Uber.

Regrettably, foreign multinationals have largely been bystanders to innovation of Chinese origin. However, the rapid changes in China’s innovation context is forcing them to react.For example, in the automotive industry, transformative trends such as electrification, autonomous driving, connected and intelligent vehicles and “mobility as a service”, which combines multiple private and public transport options for users, are forcing even the leading global carmakers to adapt. Across sectors, foreign companies are eager to connect to digitally savvy Chinese consumers through means such as super-apps like WeChat and online payment systems like Alipay and WeChat Pay.

Belatedly, foreign multinationals have began to recognise the need to learn from China, to innovate in China for China and perhaps even for the world. This will not be easy, as foreign companies need to embrace China as a breeding ground for innovation and for new thought leadership in business strategy. To do this right, they have to put China at the core of their global strategy, instead of seeing it merely as a market, albeit an important one.

So far, most of the foreign multinationals’ localisation efforts have remained basic – hiring local managers and assigning them only roles involving execution, while strategic planning and decision-making take place outside China, either in global or regional headquarters. Not only is this process not fast enough, it also does not take into account sufficiently the changes in the overall China context that can have a disproportionately large impact on a company’s China, and even global, strategy. Foreign multinationals should add substance to their localisation plans by appointing local thought leaders to senior levels, with the appropriate decision-making power and resources.

Foreign multinationals have tended to try to run their business in China by themselves, perhaps with some joint ventures here and there. Going forward, that won’t be enough as the changes in China, especially in innovation, will require capabilities beyond those that foreign multinationals are aware of. They should adopt a more open-minded approach with the idea of business ecosystems in China, and form collaborative partnerships with local companies, including established companies, start-ups, academics and research institutions, to augment their capabilities on the ground.

Like every new measure that comes out of China, the new foreign investment law will not be immune from scepticism from outside. However, the new law signals a friendlier environment that enables foreign multinationals to capture greater value in one of the world’s most important and dynamic markets. In the meantime, they should remember that in this ever-changing, increasingly competitive landscape where innovation is critical, they need to step up their game in China to capture the potential that the market offers.

In every consultant, there are bits of being a problem solver, a reporter and a process manager. The way these attributes manifest depends on the person. Most consultants believe they are problem solvers. In reality, lots are more inclined towards the latter two attributes.

By Edward Tse | February 2019

Dr. Edward Tse’s article on China’s philanthropy was published in the augural issue of Social Investor, commissioned by the Chandler Foundation.

From e-commerce platforms and Internet mobility service providers to AI and blockchain developers, Chinese technologies companies are transforming China’s economy and changing entire industries – including philanthropy.

China has a long tradition of giving, although it stagnated for roughly three decades when wealth was nationalized under the rule of Mao Zedong. Today, China is home to more billionaires – 819 in terms of US dollars – than anywhere else in the world, outnumbering the US and topping the Hurun Global Rich List 2018. And China’s super-rich are increasingly engaging in philanthropic causes.

According to Harvard University and UBS, between 2010 and 2016, donations from the top 100 philanthropists in mainland China more than tripled to US$ 4.6bn, and 46 of the wealthiest 200 Chinese billionaires now have charity foundations. Giving is much more common among ordinary citizens as well. It was reported that early in 2016, more than 20% of the total charity in China came from individual donors, a number that has grown steadily over the years.

Corruption and Transparency Woes Impede Progress

Despite those growing numbers, the philanthropic industry has been plagued by corruption and a lack of transparency. These are especially prevalent with non-profit organizations that claim to be government-supported.

In 2011, for example, a woman named Guo Meimei received a substantive amount of money from an official at the Red Cross Society of China, then flaunted her luxurious lifestyle on social media. In 2012, to cite just one other example, the China Charities Aid Foundation was accused of money laundering and embezzling.

For private philanthropists, a number of institutional and social barriers make it difficult for them to build, promote, and sustain charitable organizations. Policies mandating high expenditure rates and low administrative costs are two such barriers. Private foundations are required to spend a minimum of 8% of their previous year’s assets, making it almost impossible to grow an endowment. As a result, philanthropy remains a largely monopolized, state-run sector, and donations are largely limited to a few causes: education, poverty alleviation, and healthcare.

Technology – the Great Gamechanger

However, new technologies have helped bring innovative approaches to philanthropy and encouraged broader participation.

Tech giants, in particular, have already learned to take advantage of their branded merchandises to involve the general public in philanthropic activities. For example, in response to the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in Sichuan, Tencent, the company behind China’s biggest social network as well as the largest gaming company in the world, established an online donation platform. More than half a million people contributed, raising a total of US$ 2.9m. Tencent added donation options to WeChat, the instant messaging and social media app with one billion monthly active users, and allowed users to give any amount with a swipe of a finger, making philanthropic engagement easier than ever.

New technologies have created more diversified ways of giving. The rising popularity of fitness apps in China has inspired tech companies to incentivize giving among the younger, more health-conscious, generation. Through the Xingshan (“doing good”) app developed by the Beijing-based company iMore, users record the number of steps they take each day, which is then “donated” to charities through corporate sponsors. By the end of 2015, users of Xingshan had walked a total of 2.8 million kilometres, raising more than US$ 4.6m for 52 different public welfare organizations and projects.

Facing the troubled reputations of charitable organizations, new types of charity platforms have stepped in to address both transparency and accountability issues. Real-time updates on donation collections, along with different verification systems, guarantee the funding reaches the right people at the right time. For example, JIAN Charity – launched by Alibaba’s Cainiao Logistics in 2016 – is an online donation platform where people can place orders and then track the real-time location of the items they donated.

When it comes to smaller donations – often a much more manual process – this kind of tracking can be challenging. By encoding the lifecycle of each donation on a blockchain, Ant Financial, a subsidiary of the tech giant Alibaba Group, addresses these transparency concerns and significantly reduces operating costs.

Embedded within a larger digital ecosystem like that of Alibaba’s, philanthropy has an even more magnified potential. On Taobao, an online shopping site, sellers can register for the “Treasures for Charity” program, allowing them to donate a portion of sales revenue to non-profit projects. Sellers not only draw more customers but this also boosts their conversion rate. Even though the per-deal donation can be as low as US$ 0.0058, the cumulative effect is significant: in 2017, 1.8 million participating sellers and 350 million buyers donated a total of 245m RMB (US$ 35.7m) to charity projects the world – owing to the enormous transaction volume and user base on the e-commerce platform.

A New Era for Philanthropy in China

China’s private wealth continues to expand, and philanthropy in the country is on an undeniably upward trajectory. New technologies are unlocking more inventive forms of giving, which become more synergized with companies’ mega business ecosystems. Public awareness about philanthropy is rising, while non-profit organizations are regaining their credibility and trustworthiness. I expect a brighter future.

“Like himan, organizations are driven by their subconsciousness. ‘Business as usual’ is the norm. That’s why many co’s can’t cope with today’s fast-changing environment. The leader’s job is to raise the level of consciousness of the organization so it’s fully alert.”

“The basic requirement of a qualified consultant is to excel in three types of leadership: Thought Leadership, Client Leadership and Team Leadership. Deficiency in any one of these dimensions would make a consultant incomplete.”

Everything in the world is a duality (underpinned by a union or non-duality). Sun and Moon. Yin and Yang. Order and Chaos. Intellect and Creativity. Strategy and organizations all manifest in terms of duality. The best problem solvers are those who are aware of this and can consciously balance the forces within the duality in a dynamic manner.”

With major disruptions taking place on both the demand and supply side epitomized by technological changes, massive market scale and gradual retorms, China has become the world’s leading business laboratory. The country has transcended its identity as a market or a manufacturing and supply base, it has become a definitive source of cutting edge intellectual capital on strategy and business. The radiation of that source to rest of the world will impact how executives, investors, academics and professionals expand their thoughts on businesses.

Organizations are consisted of people. While most people are disillusioned by what their mind tell them, the same thing happen in organizations but with a much bigger scale. This is what we call “organizational subconsciousness.” Left to its own course, this could be dangerous and could lead an organization to deprivation. The job of a leader is to lead the organization to build and sustain its “organizational mindfulness.”

Quantum physics tells us that the world is not entirely physical nor entirely deterministic. Same applies to organisations. While there are physical and deterministic aspects to an organization, there are also non-physical and probabilistic aspects. Leaders must understand this in totality and incorporate this understanding in leading an organization forward.

有人说:“我们已经不是咨询公司,而是伙伴公司。” 哦。正确的咨询是专业而不是生意;以客户的价值放在最重要的地位。咨询顾问与客户的关系是一种共生的关系,而不是一项买卖。所以咨询顾问就是客户的伙伴。咨询公司亦即等于伙伴公司。

Problem solving is both a leap and also iteratiions. It’s a leap because at all times, a consultant needs to have clear hypotheses of what the answers to the problem ought to be. However, the hypothesis by definition would evolve as the consultant gathers data and carries out analyses along the way. At any given point in time, the consultant needs to have a vision of what the end answer would be. Usually that vision is pretty blurred at the beginning but as data come in, it would become clearer. However, with more data, newer vision would emerge and that is often blurred. It will become clearer as more data come in. This cycle of iterations will go on for a number of times till an acceptable picture evolves. That picture may have some resemblance with the original hypotheses but often there are plenty of differences. Leaps and iterations are the intrinsics to first-principle problem solving.

By Edward Tse | SCMP

Edward Tse says the trade war is helping to accelerate the mainland’s reform and innovation

Original published by South China Morning Post on February 4, 2019. All rights reserved.

In trying to curb China’s supposedly unfair trade practices and substantially reduce its trade deficit with China, the United States is unintentionally helping to accelerate China’s reform and innovation.

Washington’s trade war has gained support from many in the Sinophobic circle of politicians, businesses and lobbyists, who have long complained about Beijing’s treatment of foreign businesses, especially those from the US, on issues such as intellectual property protection, forced technology transfer and market access.

However, while it is arguable that China’s market liberalisation could be faster, it is unfair to say Beijing has blocked most foreign companies. In the tech sector, pundits lament that Facebook and Twitter are blocked in China, but neglect to mention Apple, Amazon, Bing, LinkedIn, eBay and Airbnb are not.

While Chinese tech giant Huawei has met with the American and other governments’ roadblocks overseas, its American counterpart Cisco continues to do business in China. As The Economist’s Schumpeter column notes in the June 28 edition, the picture of American firms being victimised in China is exaggerated.

Since US President Donald Trump’ tariff war broke out, China has accelerated the opening of its market to foreign companies. Last April, Beijing set a timetable for phasing out foreign ownership limits in the automotive industry. It is also easing curbs on sectors such as banking, securities, insurance, agriculture and aircraft manufacturing. Recently, BT Group became the first non-Chinese telecom company in China to get a nationwide operating licence. S&P Global’s Beijing-based wholly-owned subsidiary was also given a green light to enter the Chinese bond rating market.

Source: Internet

Reform is also coming to the private economy. To boost the private sector, Chinese President Xi Jinping met entrepreneurs last November, and China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission chief Guo Shuqing followed up with a statement that no less than 50 per cent of new loans should go to private businesses.

At the same time, China is stepping up mixed ownership reform, that is, diversifying the ownership of parts of the state sector. According to the National Development and Reform Commission, 100 more state-owned enterprises will join the mixed-ownership reform programme. Along the way, many “zombie” enterprises will be eliminated.

To improve the protection of intellectual property right, China’s top court has started to rule on intellectual property cases since the beginning of this year; laws are also being drafted to ban forced technological transfer.

In Davos, Chinese Vice-President Wang Qishan stressed that China would continue to carry out structural reforms and adhere to multilateralism.

Last November, The New York Times wrote in a special report: “The Chinese economy has grown so fast for so long now that it is easy to forget how unlikely its metamorphosis into a global powerhouse was.” In fact, China owes the remarkable resilience of its economy to its own evolving development model of “three-layer duality”.

At the top, the central government sets goals and directions, giving the rest of the country clear targets to follow. At the grass-roots level, private entrepreneurs have re-emerged and become a major force in driving the growth of China’s economy. And in the middle, China’s local governments channel their resources into national and local priorities, often competing but also collaborating within regional clusters. To this end, they work closely with entrepreneurs who bring innovative ideas to bear.

Undoubtedly, the current trade dispute has generated much uncertainty and volatility for China, as well as the rest of the world. It has exposed a fundamental mistrust of China in certain parts of the West, and given some Western businesses an opportunity to amplify their long-standing concerns about China, justifiable or not, through their respective chambers of commerce. This should have woken up the Chinese government to the fact that it needs to adjust its approach. This is why Beijing is reinforcing its commitment to globalisation and accelerating reform.

Source: Internet

The short-term issues brought on by the trade dispute would naturally unsettle some foreign multinational companies operating in China, but for many others, especially the larger ones, China has become so strategically important that they must figure out a way to overcome the challenges.

China’s innovation – the fast-evolving consumer demand patterns, rapidly developing government policies and regulations, increasingly prevalent tech-enabled business innovations, and the emergence of bona fide innovative and competitive local companies – has led many foreign multinationals to the realisation that what they have learned in the West won’t give them an advantage in the local market any more. Their success in China is no longer guaranteed if they rely only on what they already know. They will need to learn how to innovate in China, for China, and also in China for the world – and this won’t be easy for many.

China has reached a turning point. The age of single-minded pursuit of growth is over, and there will instead be a focus on refining the country’s economic structure, quality and sustainability. However, many in the West and even some within China are doubtful about whether Beijing will be able to make the necessary changes in a timely manner.

The challenge remains for the Chinese government to demonstrate its commitment and ability to fully implement the changes. Paradoxically, the pressure from outside, intended to thwart progress, is likely to push China into more reform and opening. Expect new waves of developments and new opportunities for companies from all over. The companies who can seize these opportunities will be among the true winners in the trade dispute.