About the Interviewee:

Dr. Edward Tse

Founder and CEO, Gao Feng Advisory Company

About the Interviewer:

Jim Euchner

Chief editor at Research-Technology Management, a US business journal

For more than two decades, Edward Tse has lived and consulted in China and observed the country’s dramatic transformation, one driven by a new entrepreneurialism and encouraged by the Chinese Communist government.

He has seen countless multinationals misread these changes, and a few grasp them. In this interview, he discusses the opening of the Chinese economy, the role of Chinese entrepreneurs in the resulting growth, and what multinational companies can do to succeed in the large, growing, and dynamic Chinese economy.

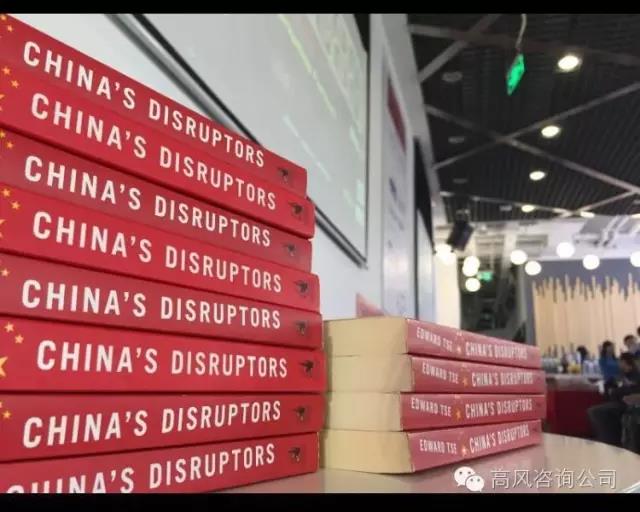

JIM EUCHNER [JE]: Your book, China’s Disruptors, makes a pretty compelling case that innovation is thriving in China. It’s a surprise to many who see China in the narrower role of a contract manufacturer or an imitator. What has happened in the last 8 or 10 years that has changed how China is innovating?

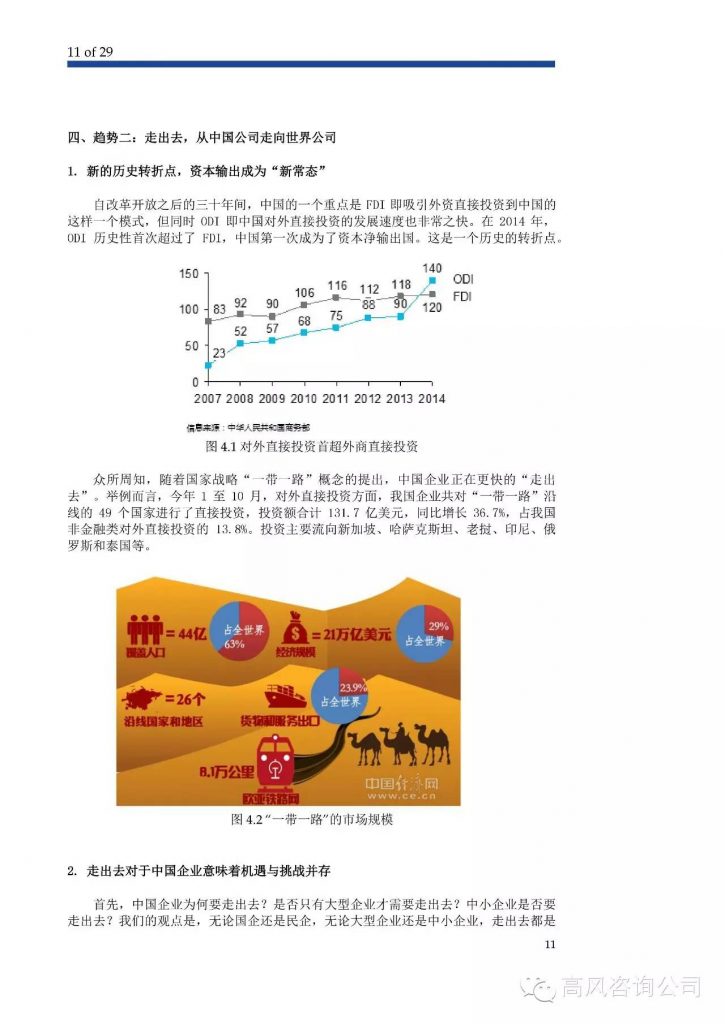

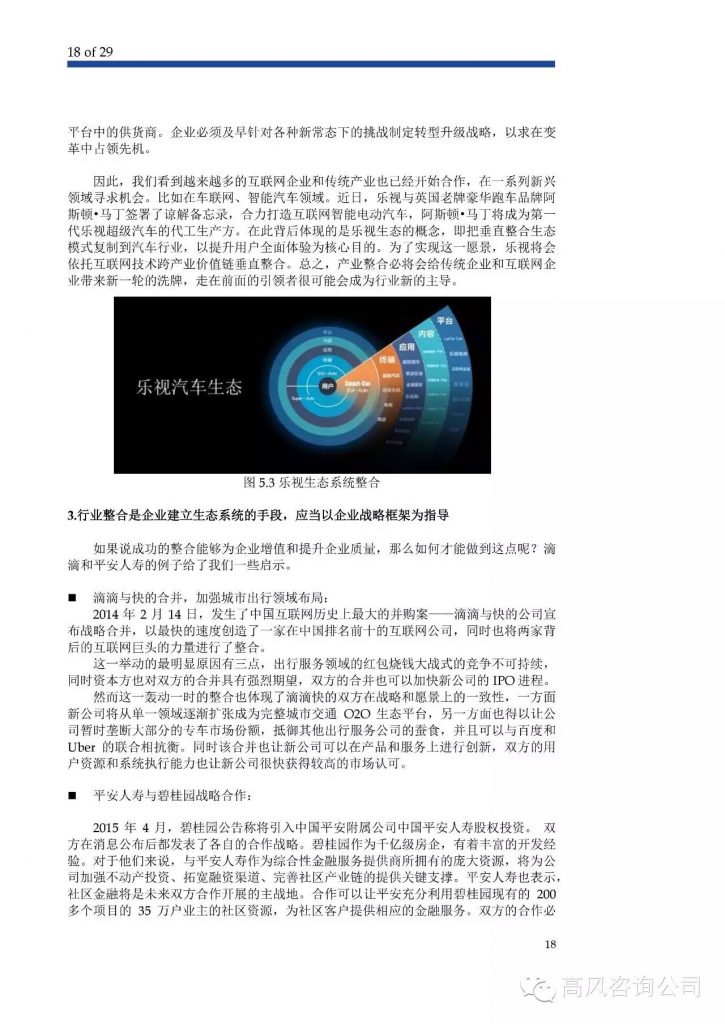

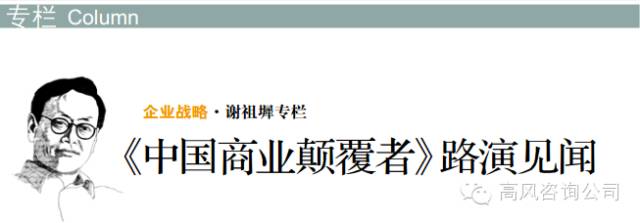

EDWARD TSE [ET]: One of the biggest impetuses was to open up the private sector in China. For a long time, the Chinese economy was dominated by state-owned enterprises [SOEs]. And while the SOEs have contributed in their own ways to the development of China, business innovation has come largely from the private sector. The private sector has been growing very, very rapidly, which the mainstream media in the West have not fully reported.

The entrepreneurs in China, by definition, are looking for ways to grow their businesses, and many of them are looking at innovation as the way to differentiate themselves from their competitors. And, of course, technology has become a very important enabler—in particular, the development of the Internet. The wireless Internet has been especially important over this period. It may surprise people that China is really a very significant Internet nation. The enabling factors of technology and thriving entrepreneurship in the world’s most populous country have driven the change. There are other factors, as well, but I think these two are probably the most significant ones driving innovation in such a fast and significant manner.

JE: Can you talk about the dance between the opening up of the economy and the official control of both the communications infrastructure and the state-owned enterprises? How does that dance work for the entrepreneurs?

ET: It is certainly true that China is still a very governmentcontrolled country; in many cases, there’s not a full degree of freedom in what people and companies can do. The interpretation of that in the West is that, therefore, it’s very difficult for the Chinese to be innovative. And also, perhaps, the Chinese are not very happy. This is only partially true. In reality, although the control of the government is very, very significant, the entrepreneurs are still able to grow in their own ways. It’s a very interesting case, because it’s becoming a duality in the development of the Chinese economy.

While the state-owned enterprises remain strong in some of the sectors, the private sector also has been thriving in its own ways at the same time, despite not having 100 percent economic liberation (so-called freedom). In a way, the Chinese government has been very, very supportive, in terms of working with the private entrepreneurs and in innovation and entrepreneurship. They have not in general tried to block the development of the private sector. The government, in fact, is encouraging almost everybody in China to be entrepreneurs and to be innovative. It has developed into a very interesting case; despite the imperfections in the society, it is thriving in its own way, which I think defies the assumptions that many in the West have made about the development of China.

JE: Yes, I think so. I had a chance on a trip to China to visit with some entrepreneurial firms, and I was surprised by their willingness to take risks and to invest in the development of new technologies and new processes. The management was nonbureaucratic; it was decisive. Did I just see a good example?

ET: No, what you said sounds right. Entrepreneurial thinking is an extremely widespread and fast-growing phenomenon in China. It is spreading across China, not only in one or two geographic areas; it’s not only in big cities like Shanghai or Beijing.

As you go around China, from the eastern seaboard, where it’s more developed, all the way to the inland area, down south to Guangdong, you see the same thing. Shenzhen is one of the world’s most innovative technology hubs. You see that all around China. People are willing to take risks.

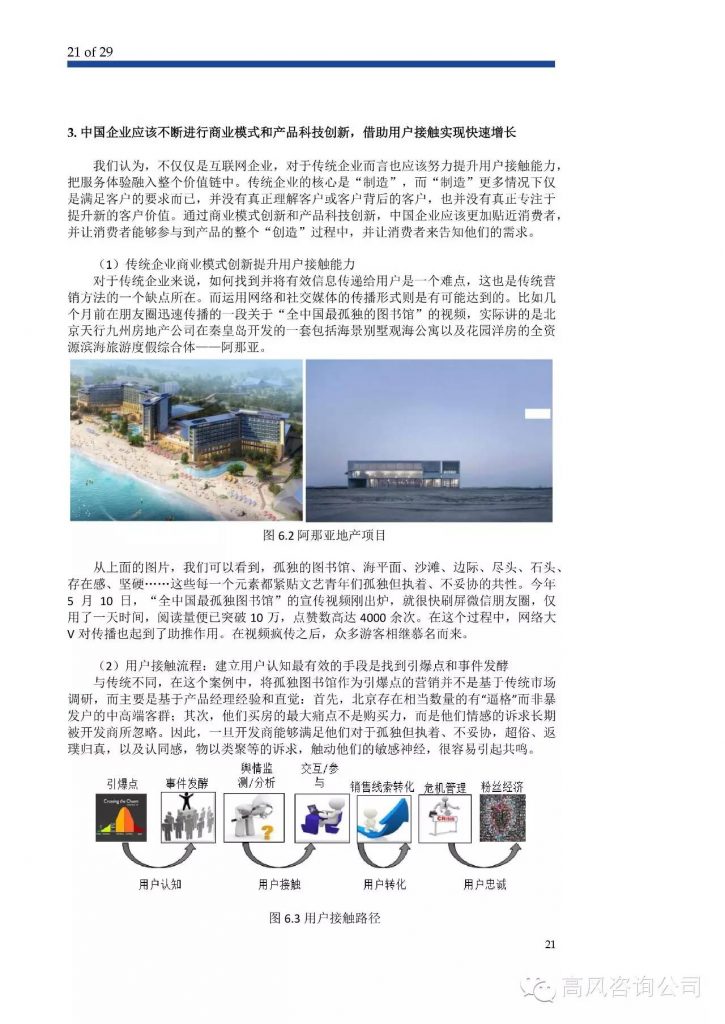

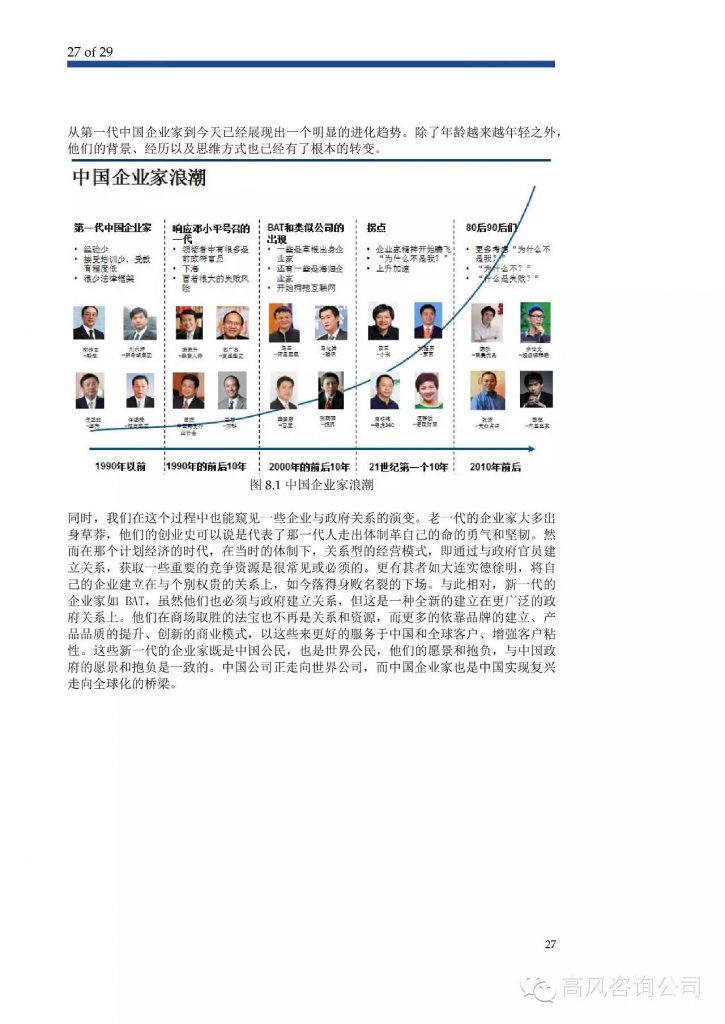

I have found the entrepreneurs I have met in China to be quite bold, and they’re very thirsty for knowledge about technology. They’re very thirsty to understand what the latest technology is and how to apply it to business, whatever makes sense. It’s happening across age profiles. The entrepreneur in China is actually getting younger. We’ve got a lot of young people, who we call the post-80s and post-90s, who have become entrepreneurs. Many of them don’t want to work for big companies anymore; they want to be successful, and they have an urge. They see predecessors, people like Jack Ma from Alibaba and Pony Ma from Tencent. They aspire to become the next Jack Ma or the next Pony Ma.

It’s very encouraging. Of course, entrepreneurship is a low-probability game. Many of these entrepreneurs won’t be successful, certainly at their first attempts. But this has not deterred these young people from all over the country from trying to make it happen. China today actually is culturally accepting of people who fail. If they try and they fail, that’s okay. People can come back again. It’s a very different culture compared to the China of 20 or 25 years ago. Entirely different.

JE: In your book, you profile Alibaba and Tencent. Both had early failures, and yet they ultimately achieved—I hate to sound ethnocentric, but they achieved the great American dream. They achieved the same things we think of the most successful entrepreneurs in the West as having achieved.

ET: Exactly. It’s the pursuit of the same values or ideals, but it’s happening in a very different political and social context. It’s very interesting. I think that there have been assumptions made that for these sorts of inspirations, innovations, or breakthroughs to happen, you have to have a certain context, in politics and the organization of society.

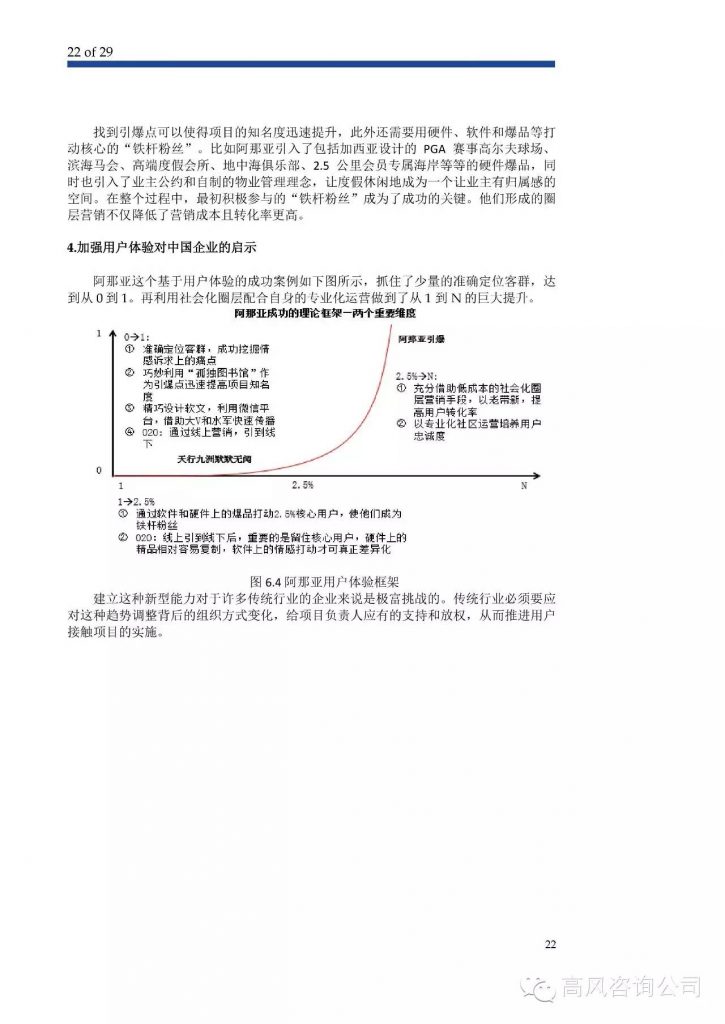

But I think that the Chinese phenomenon is proving that perhaps there’s another way.

JE: It will be interesting to see. In your book, you talk about four things that are driving growth in China, with the acronym SOOT: Scale, Open, Official support, and Technology, especially the wireless Internet. Can you start by talking about the scale effect? There is a large, emerging middle class in China. Is its growth akin to what happened in the US after World War II, where a large number of people moved into the middle class, and there was a bootstrapping going on as the middle class created demand, which drove a growth in good jobs?

ET: In terms of actual scale, it’s bigger than even the US after the Second World War, since China is the world’s most populous country. So the scale is significant. But of course, before the opening up of China, up until the Cultural Revolution, China was closed and the Chinese people were poor. Although there were a billion people, they were not really consumers. But during the rapid economic rise of China over the last 25 years, a real middle class has been developing. And this middle class, depending on your definition and depending on whose analogies you believe, ranges anywhere from 200 million to 300 million or more people.That’s not a small number. And that number will only continue to grow.

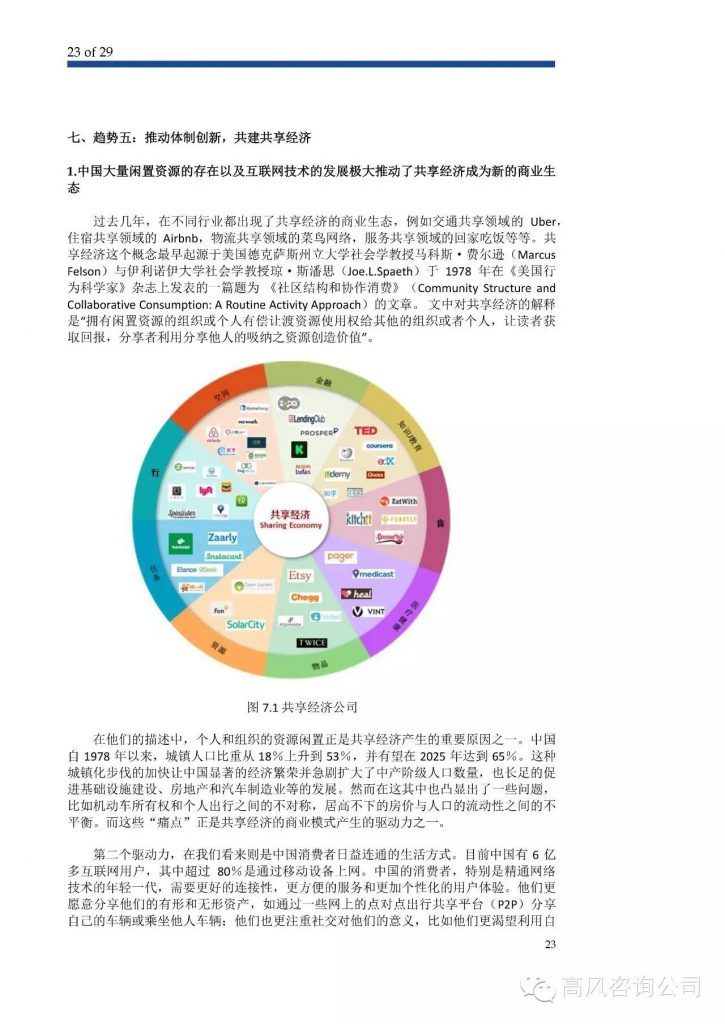

Source: Baidu

At the same time, it’s not only the middle class consumers who are driving demand. We’re also seeing demand from the lower-tier consumers, as the rural areas in China are also undergoing major changes. Chinese entrepreneurs have benefited from the fact that the scale of the market for them is significant and, mentally and culturally, many of them are quite willing to take their business model innovations to the market, even though that business model may not be 100 percent perfect. They go to the market with a somewhat imperfect model, use the market to scale up the business and to experiment with the business model; they use the feedback from customers to learn and adapt and refine the business model. The scale of the China market is very, very important because it allows that scaling up in a very fast manner, which allows people to adapt and to improve.

JE: That makes sense. The scale and the pace are two different things. The pace of change is also staggering. How does that play into the entrepreneurial activity there?

ET: The pace is happening in two ways. One is on the demand side; the other is on the supply side. The demand side is driven by the rapid increase in income levels, so everything that’s related to consumers has been changing very rapidly; as income levels go up, people gravitate more to lifestyle needs rather than just the basic consumer needs. That doesn’t mean that the basic needs are not necessary; they’re still very necessary. But at the same time, the upper end of the needs pyramid is also developing very quickly, and it’s happening within a very compressed time frame and with a huge volume. That is what is driving the pace of change on the demand side.

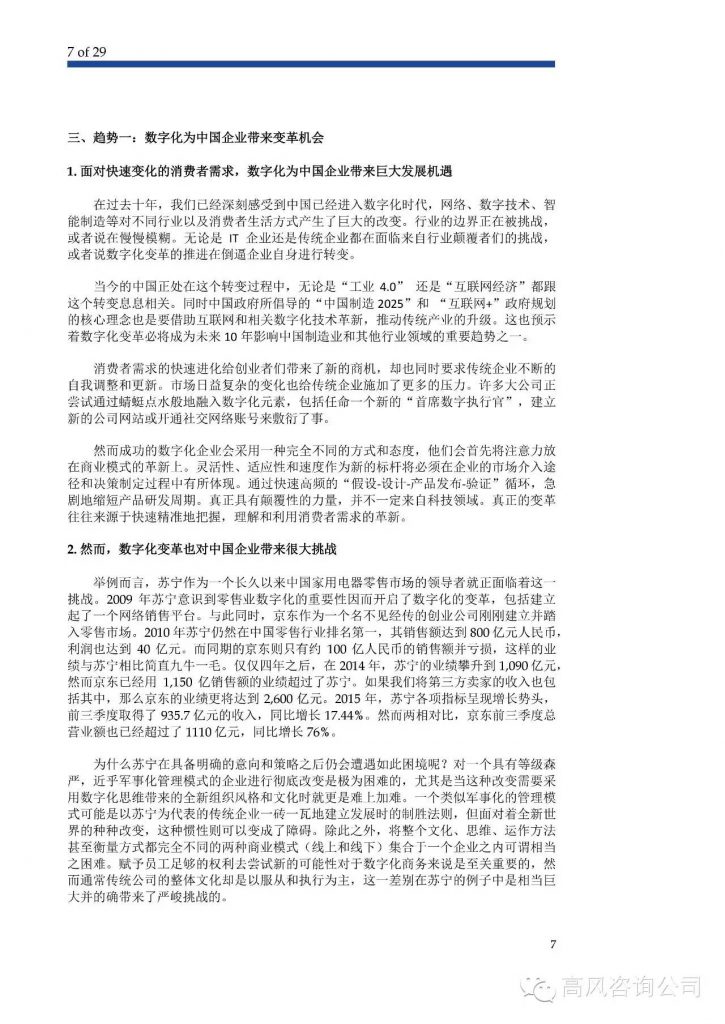

On the other hand, the pace of change on the supply side is also very significant. The underlying driver for all of this is the gradual transition of China from a planned economy, something like the former Soviet Union, to a so-called market economy. Unlike the Soviet Union, which accepted the IMF recommendation when the Soviet Union collapsed and took on the shock therapy, where everything had to be privatized overnight, the Chinese moved more slowly. Deng Xiaoping actually said, “We actually don’t know how this will go, but let’s do an experimental and gradual process.” He called that process “crossing the river by feeling the stones.”

That process is still happening today. Obviously, it has its drawbacks, but at the same time, it also has a significant benefit. Every time there has been a sector that has opened up during this gradual transition, it has exposed additional imperfections in our economy. When entrepreneurs see the imperfections, and combine that with the new technologies, they see opportunities, as well. Once a sector is open, a lot of companies jump into the market and try to get a piece of the action because they see the opportunities.

From the supply side, we often see the world’s most intense competition happening in China. There are SOEs, who want to hang on to some of the market. There are the multinationals, perhaps, who want to get a piece of the action. But there are also some Chinese competitors that you don’t see in the US or in Europe. They are thriving here in China. The birth and the rise of local competitors are significant. Competition drives efficiency, and it drives innovation. With these forces at work, the pace of change is intense. It’s incredible.

But at the same time, competition also drives companies to improve. Some get it, but some don’t get it. Later on, they find out there’s an alternative way to do business that can overtake the incumbents. All of this is happening. The pace is significant because people need to survive and because people want to get ahead. We’re talking about different levels of intensity; China is more competitively intense than in many other parts of the world.

Source: Baidu

JE: As the economy opened, did it do so sector by sector? Did the government open up the entire economy, or did they choose what sectors to open first?

ET: This is a very important topic. The West, in particular the mainstream Western media, have not really clarified this point. So when they make comments on China business, they’re often comparing apples to oranges. The transition from a planned economy to a market economy has been a gradual process in China, starting about 30 years ago. And it’s still going on. In my view, it will continue to go on for decades, if not forever; 40 years ago, everything was 100 percent in the planned economy—it was closed, certainly for foreign investors. And everything was run by state enterprises.

With the economic reform that was started by Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese government has been taking industries one by one from being closed to being open. In this process, some sectors have become 100 percent open; this means that everybody, no matter whether an SOE or a private company, whether a Chinese private company or a Western multinational, can compete in that sector. There’s not much regulation. In fact, in some sectors, there’s almost no regulation except for the common rules and laws that apply, like antitrust. So, some of the sectors are already open, but other sectors are still very closed: they’re restricted to SOEs. Not even private Chinese companies can participate in these sectors, and certainly not the multinationals. We still have some of those sectors in China. Telecom operations is an example. American telecom carriers are not able to offer their services in China.

There are also sectors that are somewhere in between; they’re partially open. An example is the automotive sector. From the standpoint of manufacturing, a foreign OEM needs to have a 50/50 joint venture partner in China to manufacture vehicles. The industry dynamics are totally different between an open sector versus a closed sector, and also between an open sector and a semi-open sector. That process of gradual opening up is still happening. Once a closed sector opens up for nonstate companies’ participation, you often see a drastic change in the industry dynamics. Such changes incentivize a lot of companies to enter the market, including many entrepreneurs who want to get a piece of the action.

So the business climate in China varies a lot by industry sector, depending on the degree to which it is open and how long it has been open.

JE: That makes sense. In your book, you note that official support for entrepreneurial firms and for the environment in which they operate is very important. Can you talk about the nature of official support?

ET: One might hypothesize that because China is a Communist state, it would stifle entrepreneurship, certainly entrepreneurship at the grassroots level. That is the assumption that many people make. But that is wrong. That’s not what’s happening in China.

While the government in China is still very supportive of state-owned enterprises, and while it is trying to achieve a lot of things through the SOEs, at the same time the private sector is developing. When the government sees the fruits that the private sector is bearing, it is very, very supportive of allowing entrepreneurs to do what they’re doing.

The innovation that the entrepreneurs are doing, and the employment and the social impact that they’re creating, and the wealth that they’re creating in the process, are important to the Chinese government. So the Chinese government is not only supporting entrepreneurs but also now regards innovation and entrepreneurship as a key pillar to the future development of the Chinese economy.

JE: And what does that mean? In practice, what does the government do to encourage that pillar?

ET: In general, they are very supportive of entrepreneurs when they are experimenting with new ways of doing business or new business models. As a new business model or new innovation comes about, there may not be a full set of regulations or policies to govern the new concepts, right? The Chinese government is quite willing to work with the entrepreneurs to develop new regulations and policies that are sensible.

The government also encourages the local governments all across China to work with entrepreneurs and to invest in them. There has been a huge amount of venture capital money in different localities in China, and in many cases, the major investor was actually the local government. Local governments are starting up funds that will fund the experiments that the entrepreneurs are suggesting. That’s another way that the government is supporting entrepreneurship.

JE: How fickle is it? Could the government shift its view and affect the fortunes of these entrepreneurial firms? For example, there are an awful lot of very small factories in China; I visited a few of them. I don’t know whether it’s accurate, but I have heard that there’s a state desire that they consolidate and get to the scale that they can become more professionalized. That’s obviously going to have consequences for some of the entrepreneurs who started those businesses. How does that kind of desire on the part of the government work?

ET: In some cases, there may be government action to try to consolidate some subscale operations. And as you also know, in many sectors in China, there is a lot of capacity in production, and a lot of this capacity is not that productive. From the standpoint of the government, it’s critical that there’s a way to rationalize the capacity. In fact, we now call it supply-side economics in China. On the other hand, there are sectors that have been growing significantly without much overcapacity, and in many cases, these are driven largely, if not entirely, by the private sector; in these cases, the government is not blocking private businesses unless there is major risk of fraud. And these firms can grow to a scale that is extremely dominant.

Alibaba is one case of a very significant firm. Tencent or WeChat is another. We’re seeing this phenomenon over and over. The government is not blocking these private entities because they’ve become so significant and so big. In fact, the government is encouraging them to continue to develop innovation. So two things arehappening at once. There is overcapacity in some sectors, which causes the government to respond, but there is also continued encouragement of companies that are thriving and developing dominant positions in their spaces.

JE: That’s helpful. You just mentioned what you call the BAT, or Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent—the three big, very successful, Internet-based companies. Can you say a little bit about them?

ET: BAT—Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent—are the leading Internet tech companies in China. They’re all private, entrepreneurial firms; they’re not state-owned. They were formed at about the same time, towards the end of the 1990s; none of them is more than 20 years old. They’re all growing significantly. Alibaba had its IPO in the US two years ago, and it was the largest in US history. Tencent is listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, and it’s now the most valuable company in all of Asia. These companies have become very dominant in China.

Source: Baidu

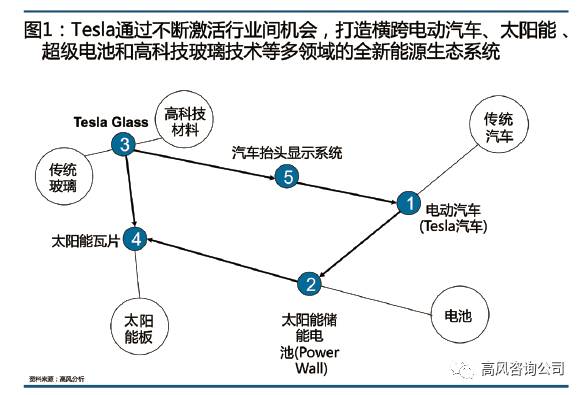

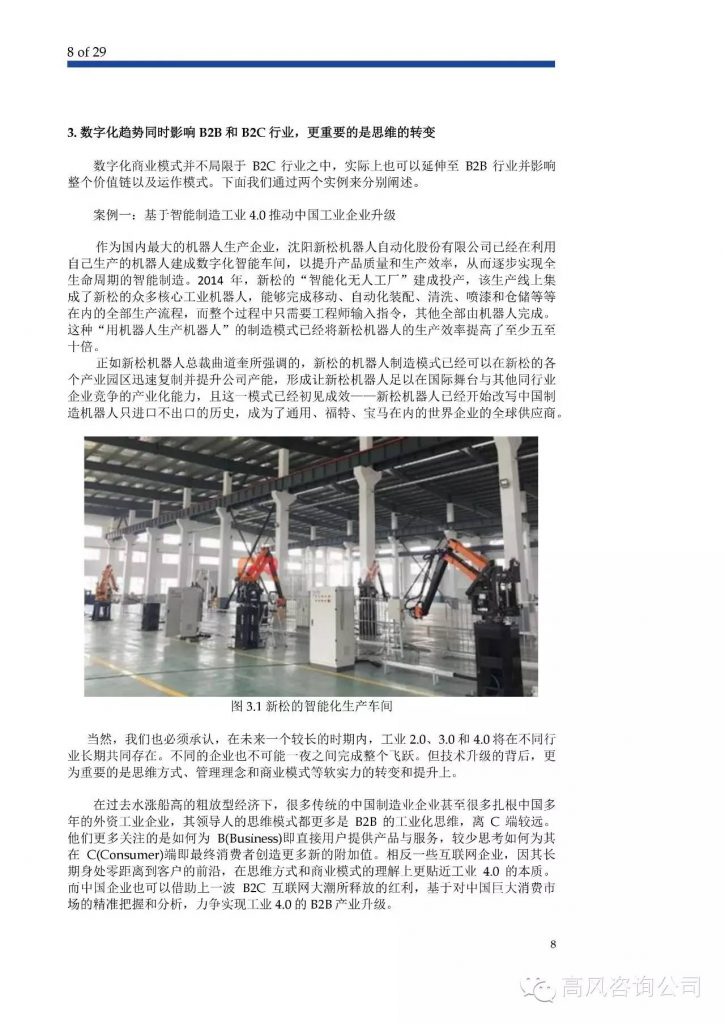

But their positions are somewhat different. Baidu started with the search engine business, kind of like Google, but now is very much shifting into artificial intelligence [AI], because they view AI as the future. Alibaba has built itself into a diverse business ecosystem, but the core is still in e-commerce, kind of like Amazon and eBay. It has launched various e-commerce marketplaces, including B2B (Alibaba.com), C2C (Taobao), and B2C (Tmall) models. They also have created businesses in cross-border e-commerce, mobile payment, Internet finance, smart logistics, cloud computing, and many others. Tencent started off mostly as a game company—video games and online gaming, and online games have become a significant business for them. But probably their most influential and most commonly adopted business is WeChat. It started off as an instant messaging platform, like WhatsApp, but now is basically a lifestyle and business application. People can do virtually anything on WeChat. And it’s a very, very sticky platform.

All of them are very significant in size and dominance, but each finds its own areas of focus. BAT is at the core of what a lot of people look at as the tech sector in China.

JE: Something that I had not fully appreciated is that there are, in a real sense, two Internets. There’s the Internet in China and the Internet in the rest of the world. Some people talk about the Great Firewall. How important is this firewall to the success of these companies? In some sense, they’re protected against competition from companies like Google because Google won’t comply with the politicalrequests or demands of the government. It’s a differently open Internet. Can you comment on that?

ET: That’s a very good question, and in fact, a question that’s probably on the minds of everyone I’ve talked to about this topic. In general, the assumption, at least from people from the West, is that because of the Great Firewall, people can’t be as innovative as they can in the West, because they don’t have access to all information. Further, they assume that people must not be happy, because they don’t have access to everything from the rest of the world. And the Great Firewall gives unfair advantages to Chinese tech companies at the expense of the West. These are the assumptions.

They are not entirely wrong, but they are certainly not entirely right, either. Some US companies were really blocked: I think Facebook was blocked; Twitter was blocked. Google was not blocked, but they chose not to comply with the requirements of the Chinese in terms of censorship, and so they withdrew.

There are also Western companies in this space that were not blocked at all. They were actually quite welcome to come to China to play. This includes eBay, which tried to enter China 15 years ago, and of course, Amazon, which has been in China since the early 2000s. But despite the prominence of Amazon and Jeff Bezos, and despite the fact that there is not much in the way—the kind of regulations and policies that would prohibit Amazon from operating in China—Amazon has not been able succeed in China in the e-commerce business as it has in the West. And eBay, as I mentioned, was beaten by Alibaba hands down in two years. Alibaba is not an SOE. It had no government support, but succeeded because of its capability and its competitiveness.

So, it’s a factual mistake to claim that all Western tech companies were blocked by China because of Chinese policies and regulations and the Great Firewall. That’s only partially correct. For those who have tried, many have not been able to capture the potential of the China market. Some of the reasons relate to the China context, but most of the issues are internally driven. They are limited by their ability to really understand China and to develop the right China strategy and the right China approach. This applies not only to the Western tech companies but in general to Western multinationals.

Source: Baidu

JE: I would like to segue to what works. What have multinational companies, not just tech companies, but tire companies, auto companies, appliance companies, done to succeed as they’ve moved from manufacturing in China to development in China and finally into innovation in China?

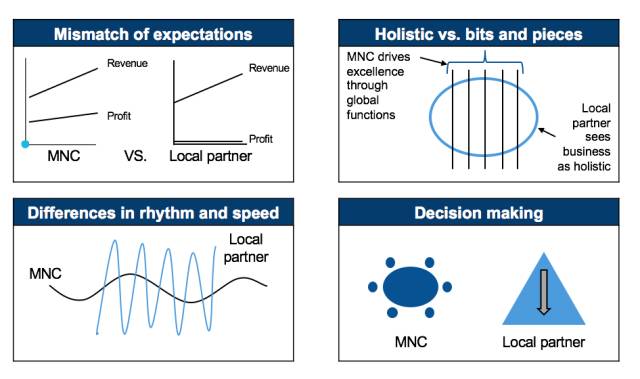

ET: If I had to pick one area where the multinationals have really failed, it is that they have tended to assume that whatever they do in the rest of the world, in particular in their home market whatever product, business model, go-tomarket model they use—would apply equally in China. That is an assumption that many multinational CEOs have made. In the back of their minds, they say, “Well, we’re a successful American company, or we’re a successful German company. We’ve been in business for 50 years, 100 years, 150 years. And we are a leader or the leader in our space in the world. I understand that China is large and growing, but I can just apply my way to China.”

And when they do market analysis, what they can forget or not fully appreciate is that the China market is developing in a faster and more competitive manner, and frankly, in a much more sophisticated manner, than their experience in the rest of the world has prepared them for. The size of China, the pace of China, the degree and intensity of competition in China, the quick development of technology in China, and the willingness to learn via trial and error all contribute to the complexity. Add to this the emergence of consumers who are, from an economic standpoint, middle class, but from a demand standpoint, probably among the most sophisticated and complicated in the world.

Instead of trying to cut and paste your business model or product from wherever it originated to China, start with a really deep understanding of what the China context is. Try to fundamentally understand what China was, is, and will be in the future. And from that, try to extrapolate to what business you should be in and how you can capture the right position in China and the full potential the China market offers to you.

I have worked with a large number of clients over the years. I think that the willingness of global CEOs to do that is actually very limited, including many of the global Fortune 500 CEOs. That is actually the fundamental issue with multinationals in China, rather than China is mysterious, China steals IP, and so on. That’s 20 percent of the issue; 80 percent is the companies themselves.

JE: Can you give an example of a company that’s done it well?

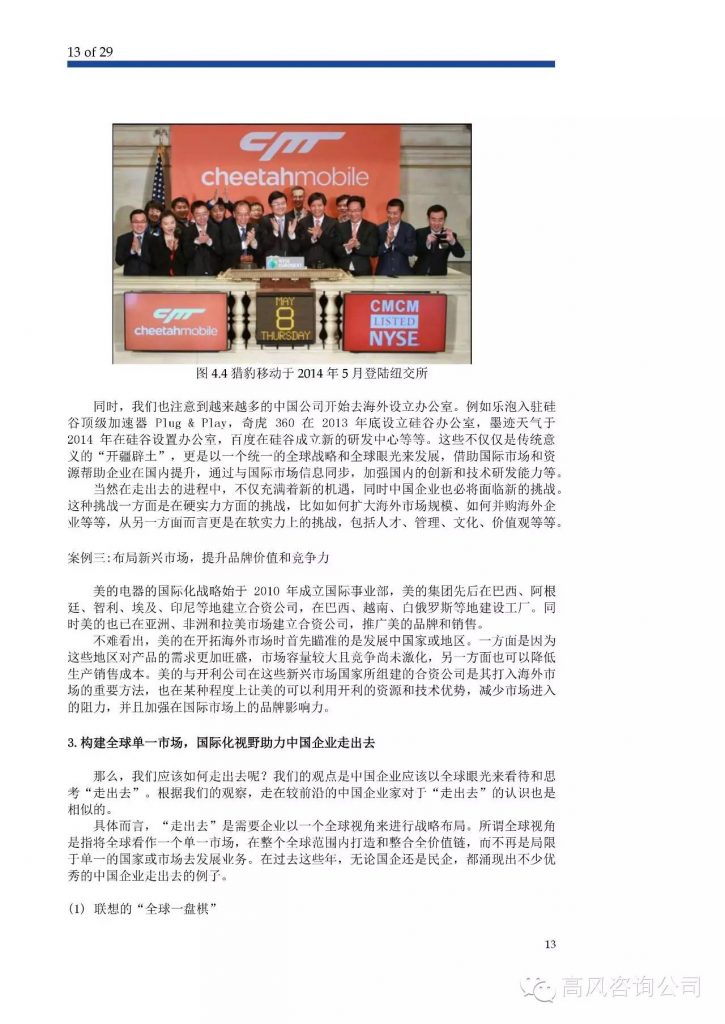

ET: There are some. The auto industry is doing in general pretty well. China is now the largest automotive market in the world. The German manufacturers and also General Motors and Ford, they’re doing very well in China. For those companies, the rapid rise of the auto market, the sheer size of the market, and the willingness of the Chinese consumer to adopt Western brands, really carries the automotive multinationals. And the market continues to grow at double-digit levels.

Source: Baidu

There are also companies that are in very intensively competitive consumer markets that are open; there’s not much regulation, and they’re really thriving. I’m talking about the sporting goods companies like Nike and Adidas. They’re really the stalwarts; they’re the leading companies. Starbucks is also doing well. Why would the Chinese like to drink coffee? Chinese people used to drink tea. Starbucks is doing extremely well in cultivating a new coffee culture in China. A latte in China is more expensive than a latte in America.

Honeywell is a prime example of an industrial company that has gotten it right in China. Honeywell is a multibusiness-unit industrial company with a variety of B2B divisions and a few B2C business units as well. China is now the second largest market in the world for Honeywell, after the US. It contributes the largest growth for Honeywell. They are a good example of a multinational that gets it in China.

JE: And that is because they really took the time to understand the dynamics of the Chinese market?

ET: That’s correct, yes.

JE: One more question, in the limited time we have. When I was in China, I spoke to people about the rich startup movement in China, the equivalent of what’s going on in Silicon Valley, or Austin, Texas, in the US, or Toronto in Canada, or London. I know Shanghai has a thriving startup market, with an active VC community. How is the startup movement in China similar to and how is it different from that in the West? If a company wants to work with startups in Shanghai or one of the other centers in China, how would it operate differently there than in Silicon Valley?

ET: In many ways, the basic tenets of entrepreneurship are not that different between Silicon Valley and the Chinese centers. People are willing to take risks. People see the pain points, and they want to turn the pain points into opportunities. People are enthusiastic about the opportunity and are willing to take risks to act on it. So the basic tenets are more or less the same.

The pace and intensity of entrepreneurship in China is unique, however. You often find, in a very short period of time, a lot of companies are trying to do the same thing or similar things: everyone sees the opportunity, and they jump into it. Very often, the market becomes quite crowded, overly crowded. And when it’s overly crowded, some of the companies will not be able to make it, as in any market. That process is happening at a pace and intensity that’s faster than in any other place in the world—perhaps even including Silicon Valley. And this is happening in a period of significant regulatory uncertainty.

So from a multinational standpoint, when you work with a startup in China, you have to take a somewhat different mindset. Of course, multinationals know that these experiments are a low-probability game, and you have to go into it with that kind of mindset. But in China, the risk and also the opportunities are amplified. They’re magnified even beyond what you see in Silicon Valley. And so, when you’re working with a startup, you have to have a mindset that recognizes the higher opportunity but also higher risk. And at the same time, you have to develop internal processes for managing these sorts of situations.

JE: Is IP a specific concern? I hear it mentioned often.

ET: IP concerns are, in my view, somewhat of an excuse for many multinational companies. You do have to be careful with IP, but at the same time, you cannot let that stifle your willingness to grasp opportunities in China. It’s a careful balance, and every company needs to treat it somewhat differently. But in general, a blanket statement that because of imperfect IP protection in China we shouldn’t be bringing our products or our technology or our innovation and experimentation to China is a flawed assumption.

Over the last 10, 15, or 20 years, entrepreneurship and innovation in China have been happening, led by Chinese entrepreneurs, under a very imperfect regulatory context. The lack of protection for IP, of course, applies equally to the Chinese companies, not only to the multinationals. Yet at the same time, a lot of companies are able to innovate and experiment and create new businesses. And many of them fail, but some of them are extremely successful. One needs to be careful about IP, but one needs to be careful, as well, not to use it as an excuse to not do innovation in China. If you don’t innovate in China, you’re missing a huge opportunity.

JE: If you were advising a CTO or a leader of innovation at a Western firm, what key advice would you give for succeeding in China?

ET: My advice applies equally to the CEO, the CTO, the CIO, or the Chief Innovation Officer: you need to really understand what’s going on in China and in the Chinese market. My advice is to throw away your Western lens for a little while and truly look at China without any constraints; try to understand both the threats—the risks of doing business, but also the competitive threats—and also the huge opportunity China offers. Once you have a full appreciation of the China potential, then devise your innovation strategy and your China R&D strategy. You need to have a lot of good, on the-ground competence in China to drive these things. The capabilities at headquarters are still critical, but headquarters needs to support, not control. You need to empower appropriately. You need to have a good balance between empowerment of the local team and support from the global function. You must build a strong team on the ground, a team that understands the market and really turns the demand side from the market into innovation ideas. This kind of innovation has to be done on the ground in China because of the need to stay close to the market, and also because the competitive environment requires speed and responsiveness.

JE: What’s the best way for leaders to get it? How much time should they spend on the ground in order to really understand China? What do you recommend to someone who says, “Okay, I get your message. I want to understand China. How do I do it?”

ET: The first hurdle is mindset. I’ve seen quite a number of leaders, presidents of business units and so on, who say, “I moved to China. I’m based in Shanghai now,” and they think that gives them the perspective. But from the outside, I can see that the way that he or she behaves is actually still very non-Chinese. I think that where you’re based physically is of secondary importance; the first level of importance is having a new mindset. You can do that from Munich, Germany, or from Cleveland, Ohio, or from Houston, Texas.

Once you have that mindset, and you’re willing to use an approach that is very locally adaptive, the key is to find the right team on the ground that you can work with and that you can appropriately empower. Then, keep a very close connection between the headquarters and the China unit. You should also have good advisors to help you, to remind you, to help you steer the way. That is the basic mechanism that I have seen work.

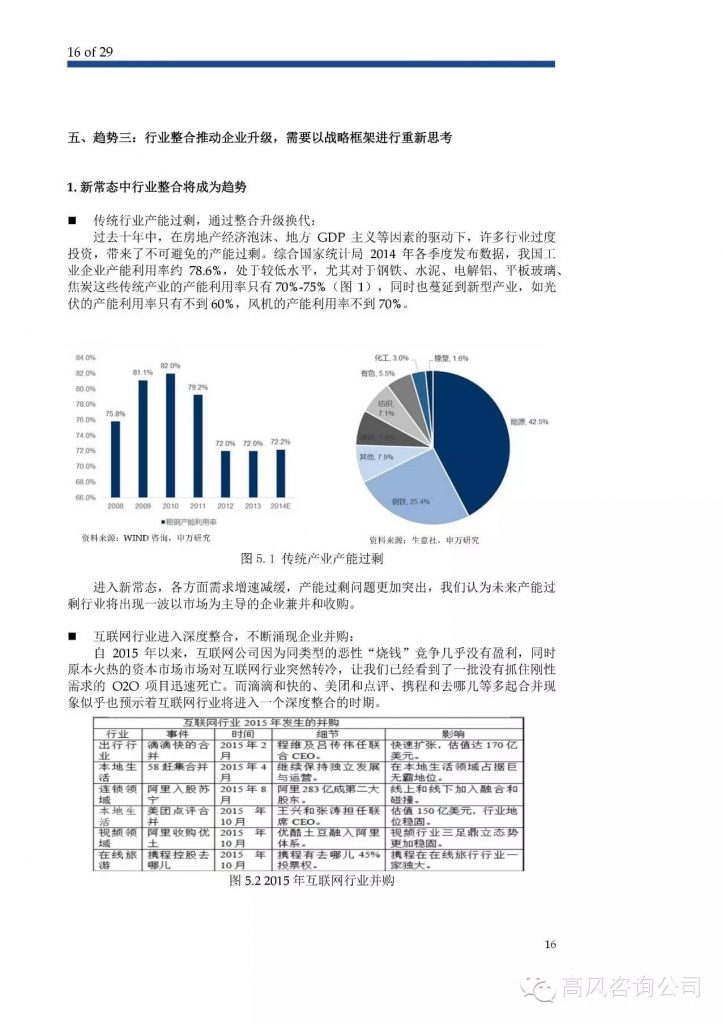

If you set it up right, it can be very powerful. That is what drove Honeywell to its success in China. It sounds very simple. But in my career, which includes over 25 years in China, it is interesting for me to observe how little multinationals have actually been able to create this mindset.